Modern Art: Striving for Meaning and Essence in the First Half of the Twentieth Century

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) was the central figure among a group of Parisian artists, somewhat misnamed les Fauves or "Wild Beasts," who reacted against the deliberate methods of Neo-Impressionism. For them, the construction of a painting through tiny dots created an effect in the retina not disimilar to the vibrato in music. For the Fauves, Pointillism destroyed the form and order, necessary to all great art, that could be created only through the organization of large areas of pure color. Here then was the first critical lesson that Matisse derived from Cezanne.

Cezanne also showed Matisse the way in other regards. As noted, the classical ordering that informed Cezanne's work attracted Matisse, and he adopted it as a doctrine of his own. Like Cezanne, Matisse believed that a work of art had to be intellectually worked-out in order to have enduring value; before even beginning, the artist had to have a clear vision of the entire composition in his mind. To be durable, a work of art had to be more than the record of the jumbled sensations of an instant.

After studying Egyptian, Greek, and Oriental art, Matisse came to the revelation that in abandoning the literal representation of movement one could attain a higher ideal of beauty. In Greek sculpture he saw that a figure could be depicted at the most precarious moment of an action, yet the moment within the action could be extracted and condensed, restoring balance, clarity, and calm. Of paramount importance to Matisse was the fact that in the hands of the ancient Greeks, scupture became durable without becoming static.

Matisse's work tends also to have a decorative quality. Of its purpose he wrote, "what I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter, an art which might be...like an appeasing influence, like a mental soother, something like a good armchair in which to rest from physical fatigue."

Henri Matisse, "Red Room" (1908)

Henri Matisse, "Still Life with Goldfish" (1911)

Cubism

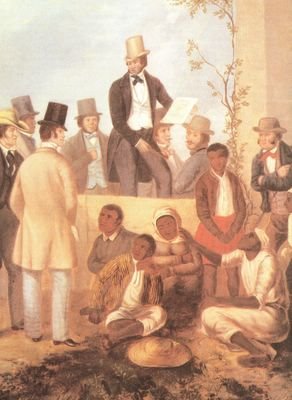

Although paintings in the style continued to be produced throughout the first half of the century, the formative period of Cubism extends from 1906 or 1907 until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Central to the movement was Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), undoubtedly the most important master of the twentieth century. Picasso began to absorb the visual aspects of Afrcian tribal sculpture after veiwing a museum exhibit at the invitation of his friend Matisse. The Fauves had been attracted by primitive art; Gaugin played a significant role in opening their attitudes to the exploration of African and Oceanic art.

As with other artists of the era, Picasso embraced Cezanne's advances of organization using the placement and rhythm of color, that is, his concepts of volume and displacement. To these ideas he married the squared, geometric shapes observed in African art. This marriage challenged the classical concept of beauty. Here the subject matter is fragmented, like shards of broken glass and not unlike the medieval stain-glass window. The field gains a certain three-dimensionality except that in viewing one is never sure if the shard is concave ro convex, solid or transluscent.

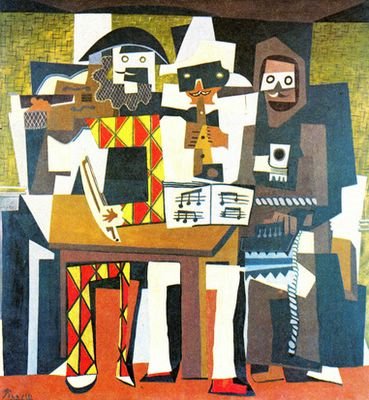

Picasso and Georges Braque (1882-1963), another cubist with whom Picasso often collaborated, discovered that depth of field could be created by pasting materials to the field. The method permitted the creation of a three-dimensional field without using the traditional methods of foreshortening or perspective, the device developed by Renaissance masters. The discovery was an extension of their concept of "picture as a tray" and resulted from the step of simply placing something on the tray. The process, called collage, permitted the image "to represent" (be part of an image) and "to present" (exist as themselves) at the same time. In time Picasso and Braque discovered that they did not need to paste materials to the canvas to create this new pictorial space. They could attain the same illusion by simply painting as if they were pasting. "Three Muisicans" employs the collage method of painting. The viewer cannot tell if the images in the foreground are painted or pasted.

Pablo Picasso, "Three Musicians" (1921)

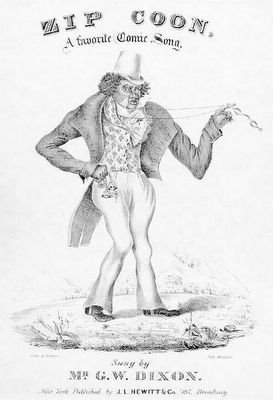

Picasso's interest in African scuplture might have influenced his composer friend, Igor Stravinsky. The two worked together on various productions by Sergei Diaghilev's Ballet Russe. Stravinsky's "additive rhythms" (see subsequent Supplemental Lecture in the Modern section and "centonization" in New Millenium) likely have African origin, and several of Stravinsky's "jazz" compositions can be definitely ascribed to the influence of scores of African-American music that Diaghilev brought to Stravinsky from a trip to America. Most importantly, African influence was coming to fruitition in European art at the same time it blossomed, after a century of melding work songs and "field hollers" to Western harmony and form, in American music as jazz and blues.

Futurism

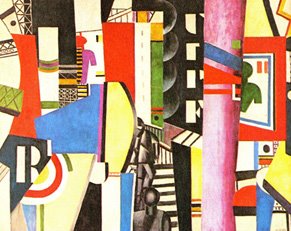

Cubism, as Picasso originally conceived it, was a classical discipline that could be applied to the traditional subject of painting such as protraits, still life scenes, and the nude. Other artists, however, saw in cubism a special affinity with the modern age, in particular the strides made in engineering and the manifestation of those strides in the contemporary landscape. The changes to the environment included, of course, power lines, suspension bridges and their complex system of cables, the lattice-work on airplane wings, and the like. A group of Italian artists who called themselves Futurists celebrated the machine. Their successes were found primarily in sculpture, but thier influence is also found in painting. Fernand Leger's (1881-1955) "The City" beautifully, concisely, and dynamically captures the modern industrial landscape.

Fernand Leger, "The City" (1919)

Another central facet of Futurism was the attempt to represent motion. The most significant outgrowth of experiments to capture the essence of motion, that is, speed, the preoccupation of modern man, was the impact upon upon viewer sensibilites in accepting of the beauty of the machine. Cinematography soon overtook Futurist painting. Marcel Duchamp, whose importance and oeuvre far exceeds Futurism, illustrates the representation of motion, here both real and symbolic, in "Le Passage de la vierge a la mariee" ("The Passage from Virgin to Bride").

Marcel Duchamp, "Le Passage de la vierge a la mariee" (1912)

Dadaism and Surrealism

Dada began almost as much as a political movement as an art movement. The aim of the Dadaist was the opposition of "bourgeosie" naturalism in any form as it appeared in contemporary art and hence the opposition of the companion "bourgeosie" morality inherent in naturalism. For the Dadaist, any imitation of nature, "however concealed," was a lie. Art must be neither realistic or idealistic to be true. Truth could be revealed only in its abstract essence.

In fact, the Dadaists had no clue what they stood for but they knew that they didn't stand for any style that existed harmoniously with society. True to their professed revolutionary confusion, they borrowed copiously and unwittingly from the styles of art around them, most notably futurism. From early on, the Dada movement had nihilistic tinges. Thier attempts to free themselves from all ancient social and artistic tradtions, set against the background of World War I and later the Russian Revolution, attracted not only 'activisits,' but also anarchists and fascists. Their slogan was chillingly straightforward: "Destruction is also Creation!"

First and foremost, the Dadaists wished to punish the bourgeosie, whom they blamed for the war. To this end, they embraced every conceivable ideal they could glean from the realm of the macabre and base to use as subject matter as an affront to the diginity of traditional subject matter. Duchamp painted a moustache on Mona Lisa and Picabia painted machines that had no functional capabilities or purpose but to mock science, engineering, and, ultimately, modern society.

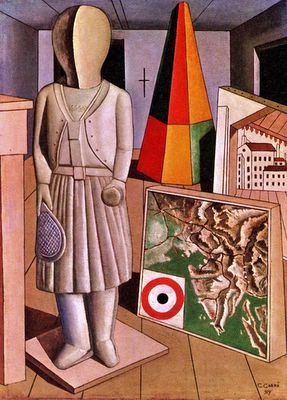

Two Italian artists, Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carra, devised a new style, the scuola metafisica (Metaphysical School). It essentially involved a dream landscape, a Romantic offshoot, in which the images portrayed had no logical connection and which seemed almost to be dream-derived.

Carlo Carra, "The Metaphysical Muse" (1917)

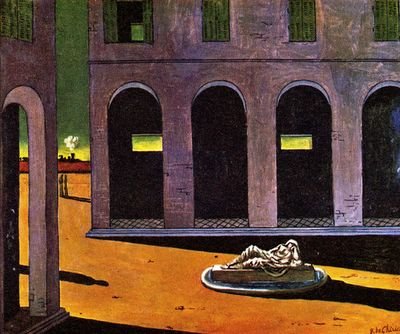

De Chirico used older devices of art, but in new ways. He used perspective, for example, for its emotional value, and in his landscapes he used objects, architecture, and light and dark to create a sense of dramatic expectancy. The viewer stands on the verge of something that will occur, though he knows the event will not be good.

Giorgio de Chirico "Place d'Italie" (1912)

Surrealism had literary origins that encompassed an experiemtnal style of writing, a variey of "stream of consciousness" that had psychoanalytical overtones. In Surrealism, symbolic imagery presented in dreams and dream analysis form the basis of poetic effect. Although the principal Surrealists began with a sympathy for Dada, the different aims of the former, a more constructive message and an underpinning in psychoanalysis, caused a historic and permanent rift.

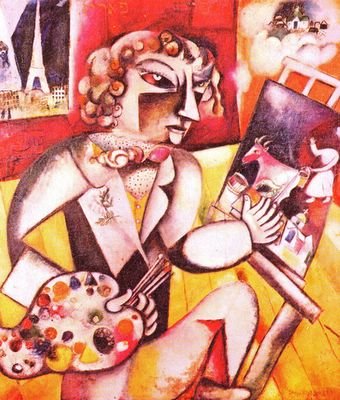

The art of Marc Chagall (1887-1985) does not entirely fit into the category of Surrealism. Its characteristics owe a debt to Cubism and his vibrant colors, what he called his 'primordial palette,' seem derived from Impressionism, at least on a superificial level. He denied these affinities, despite the fact that in the early years he exhibited as a Cubist.

Chagall, a Russian born painter, brought to his art a poetic vision that had roots in the folklore of his native country, Jewish tales, and the Russian countryside. Later in life he painted and repainted scenes from his childhood, none of which seem to have lost their persistence with the passage of time. The fantasy component causes his work to be considered with the Surrealists, and certainly his work offered to younger painters an alternative vision to that of De Chirico.

Marc Chagall, "Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers" (1912)

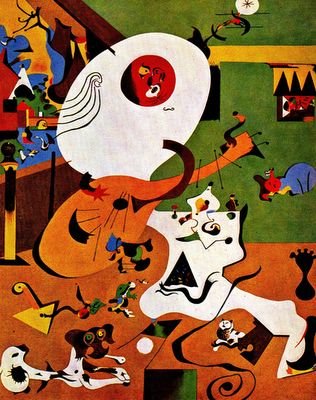

The art of Spanish artist Joan Miro (1893-1983) represents a boldy imaginative and playful branch of Surrealism. His designs have been called 'biomorphic abstractions' since they consist more of curved lines than geometric shapes. Despite the fluidity of shape, the vitality, and the light-hearted character of his work, it is no less disciplined than Cubism.

Joan Miro, "Dutch Interior" (1928)

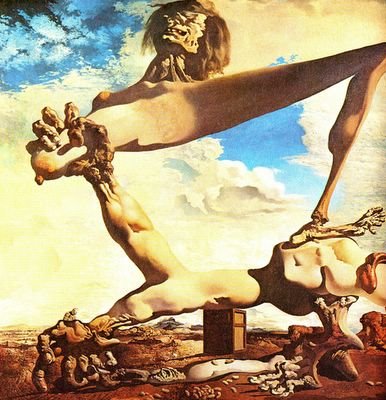

Salvador Dali (b1904) has not been very well regarded among either his fellow Surrealists or art critics. Both his art and his presentation of it have had an ingenuity and theatrical component that have propelled art and artist alike into the popular consciousness. Collegues regarded his techniques as "ultra-retrograde" and his subject matter contrived. He has, however, enjoyed tremondous commercial success.

Salvador Dali, "Premonition of Civil War" (1936)

Abstraction

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) had already developed a mature mastery of Van Gogh's style of Expressionism when he immigrated to Paris in 1912. Under the influence of Cubism, his work began a process of transformation. In each subsequent stage of evolution Mondrian moved closer to the "balance of unequal but equivalent oppositions." His quest led to find the 'right' relationship caused him to reduce his materials to black bands and three primary colors and black and white. Despite the elimination fo any representative possiblility in his work, he often assigned titles, such as "Broadway Boogie-Woogie," that suggest some relationship to observed reality.

Piet Mondrian, "Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue" (1921), detail

Abstract Expressionism

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) was one of the originators of a school of painting that enjoyed currency for a decade or so after the Second World War. Pollock abandoned the paintbrush for dribbling, spattering, and flinging as the methods of applying paint. Despite his mthods, his canvases have an undeniable emotional and aesthetic appeal. Pollock sought to "get into" his paintings, walking about on and across them and working on them from all sides. To Pollock, paint was not a passive suppstance to be applied and mainpulated. Instead, it was a store house of energy to be released. In his work methods, the internal dyanamics of a painting took care of itself. The surface and materials itself could offer its own interest including the visocsity of the paint, the interaction of the hues, the shape of the figuration as a function of the speed and angle of the impact of the paint,and the like. Undeinably, his canvases express an intense vitality.

Jackson Pollock, "One (#31)" (1950)

Pop Art

Pop Art, generally regarded to have its ken exclusively in American culture, actually had its origins in London in the 1950s. Throughout its most viable years it remained centered between NewYork and London. Its imagery, even of the earliest works, were derived from American mass media. In the style, commercial culture is viewed as an endless source of material rather than with revulsion. The most important qualities of mass-media images suitable for absorption into Pop Art are that they are popular, short-term, easily forgotten, low-cost, mass produced, designed for youth consumption, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and representative of big business.

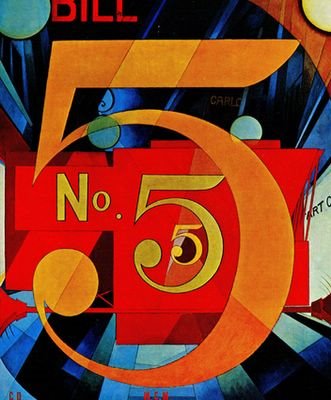

American artist Paul Demuth had actually anticipated the Pop Art style before it became established. The title echoes that of a poem written by Willam Carlos William, and the fact explains the "Bill," "Carlos," and "W.C.W" that also appear in the design. The number five appears, in the poem, on the side of a firetruck, and its repetition in the painting reinforces the impression fo the firetruck as it races past us, the pedestrian observer, in the night.

Charles Demuth, "I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold" (1928)

Andy Warhol emerged in the 1960s as the principle exponent of the Pop Art movement. He is best known for his rendition of the Campbell's soup can. He also produced series using photographs of celebrities, including Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, and Jackie Kennedy, as well as photographs of flowers and even the electric chair. Warhol reduced the images to icons by silk-screening them onto canvas, proving their capacity for mass production.