Medieval Developments

The Organization of Medieval Society: the Feudal System and the Church

Feudal government was an outgrowth of several different Roman client systems. At the foundation, the relationship of landowner and the farmer was simple: the landowner provided capital or, more often, protection, and the farmer paid taxes, rents, or both to the landowner. The tenet created two large classes, the lord and the vassal, and one smaller but critical peripheral class, the soldier. The clergy constituted a fourth class fundamental to society but not fundamental to the economic workings of the feudal system. The members of the landed class often descended from regional warrior kings but were also created by the bestowal of immunities. An immunity could be granted by the king.

The recipient of an immunity gained the right to rule over his landholdings, within the canons of civil and Divine law, but owed his ultimate loyalty to the king, the only person who could supersede his word in law. Since the king lived a considerable distance and was usually preoccupied by more pressing matters, the rule of the lord was, for all practical purposes, unchallenged. Landowners often unscrupulously added to their power by adding to their landholdings.

The Church also shared some portion of the power with the king and the lords. Divine law had its source in Christianity, and the officials of the Church were its administrators. In practical terms, the king could and sometimes did participate in making religious or superseded the Church entirely, particularly if the implementation of religious law had civil consequences. Charlemagne, for example, ruled with a free hand in all matters. His coronation as Emperor was meant to signal the coming of yet another Roman Empire, the

The Church and its properties played a significant role in the distribution of the Medieval population. Roman roads already created an interlaced highway system that permitted travel through

Vassals came under the control of the lord in a variety of ways. Some were successful free farmers who fell under increasing threat from foreign invaders such, as the Muslims who invaded

Aside from the nobleman and his family, the local Church officials, and a handful of civil administrators, the entire population of the fief existed in a state of servility. Although the nobility did not work for a living, they gainfully filled their time with war, high adventure, political intrigue, and sport.

The vassals divided into several distinct classes. The largest classes were the villeins and the serfs. Villeins were small farmers who surrendered their lands in exchange for protection but were not part of the property. By law, the villain could be taxed but only within the limits set by civil law. Serfs, by contrast, were bought and sold with the land, and their labor could be exploited without recompense at the whim of the lord. By the thirteenth century, the distinctions between villain and serf had disappeared. Surprisingly, the position of the villain did not degrade to that of serf, the position of the serf had instead improved to that of the villein.

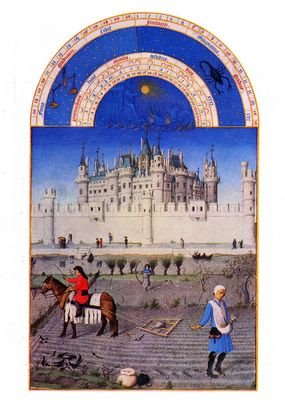

The fiefs physically reflected their class structure. The landowner, his family, and his soldiers lived within the walls of the fortifications. The vassals lived on parcels of farmland outside the gates but could withdraw into the fortifications in times of attack. The further from the fortifications the location of one’s house, the lower one’s station. The bastion against attack for the furthest houses might not be a wall, but a hedge.

Daily Life

A singular significant advance of the Middle Ages was the large scale cultivation of the land and the domestication of animals. The control over the land, which meant the clearing of significant portions of it of woods, helped to eliminate food shortages throughout the year. It also meant that not all members of the society need be occupied in acquiring food. Hence in the origin of agrarian advances one finds the beginning of professional specialization within the society and the consequent beneficial rise in the society of the quality of goods, education, and organization.

Improvements of agrarian techniques and their application did not spell the end of earlier hunting and gathering activities. Not so much of the forest had been pushed back from civilization’s structures that wild animals did not flourish. Dangerous animals such as bears often wandered in search of food into cultivated areas and presented real danger. Hunting and gathering filled the table in lean times and supplemented not only the basic available foodstuffs, but offered a necessary variety in diet and hence nutrition. Without refrigeration but with new sources available, new methods of preparing and storing food developed. For example, wine became a means to hold perishable fruit, cheese permitted a longer life to cow’s milk, and bread became important as a way to convert inedible stored grain to digestible form. Spices became increasingly important and were often used to disguise rancid meat.

Hardships of environment were shared by the nobility and peasant alike. Manor houses were dark, dank, and drafty. Many of the health hazards of the peasant house, such as smoke from wood fires used to cook and to heat, were present in equal proportions in the best houses. The walls of peasant houses were constructed of wattle and daub (mud and straw). The thatched-straw roof had a hole in the middle to allow the smoke from the cooking and heating fire to escape and duly allowed in the rain and snow. The floors were dirt, the beds were fashioned from a box of straw, and the furniture was a table and several three-legged stools.

The peasant diet was limited and monotonous. He ate bread, porridge, and cheese year round. In the summer, the diet was augmented by vegetables from his garden. Further additions came from the berries and other fruits he was able to gather and from the game he was able to kill. Game meats were fresh, but those available in the open markets were often badly cured and half putrid. If crops were bad, he suffered, and death from starvation and disease were commonplace. Beer and wine were always available, and they doubtless, and this is not said flippantly, helped dull the pain of existence.

The peasant workday lasted from sunrise until after dark. Life was not regulated by the clock, since accurate time measurement did not evolve until later in the period, but by the daily cycle of the sun and the yearly cycle of the seasons. Once the animals were secured for the night, the peasant had his dinner and a few hours for himself.

Religion and the Peasant

Throughout the Middle Ages, the portrayal of Christ began to evolve in a way that made Him more accessible to the vassal. In the early Middle Ages and in concurrent Byzantine culture, emphasis had been placed upon the glorified, omnipotent, and distant Christ. Around the tenth century, the Passion began to move to the fore. The telling of the Passion and its depiction in art made Christ more accessible by making him more accessible and more human. No longer just a remote icon, He was seen in his human suffering and sacrifice, facts of life central to the vassal, and His reward for his virtue was driven home. The shift in conceptualization permitted the worshipper to empathetically embrace Him, and prompted enthusiastic lay participation in cathedral worship and cathedral building.

For the dispossessed elements of feudal society, the crofters, vagabonds, beggars, and the like, a class of people in a chronic state of uncertainty of survival, institutionalized religion was inadequate. For the class of people outside the mainstream, standard religious ideas became inadequate in the face of developments that threatened existence, namely any disturbing, frightening, or exciting event. New types of preachers, some drawn from clerical ranks and others from the laity, emerged to teach greatly expanded interpretations of a religion that already embraced mystery, sensuality, and superstition.

Excess was part of mainstream Catholicism, in action and symbolism. Self-flagellation was common practice during the plague. The gargoyle of Gothic architecture, terrible nightmare beasts that represented evil, adorned cathedral exteriors. Some were carved into the wall, at eye level, as warnings. Large gargoyle sculptures are always mounted to face outwards to symbolize the flight of evil from goodness. In mechanical function, they were often rainspouts.

Graphic and gruesome gargoyle warning to sinners

Gargoyle rainspout on Notre Dame Cathedral

Psychological Relief: High Holidays, Feast Days, Weddings, and Funerals

The Church often furnished the majority of bright spots in the life of the peasant. Sunday Mass offered a relief from the relentless routine and labor. Special occasions were truly special. The High Holidays of the Church, Christmas and Easter, were foremost among holidays and entailed feasts, splendor, and elevated ritual. By the late 1300s, the Church calendar embraced upward of fifty holidays, or roughly one per week, that involved the commemoration of the apostles, saints, and martyrs. Most welcome to the vassal, they meant the cessation of labor. In turn the vassal supported the central source of his worship, the cathedral church, with his endowments and gifts. Inns remained open, not so much to furnish drink, but rather to furnish meals for visitors.

Other occasions that permitted feasting and social intercourse were weddings and funerals. The wake was conducted considerably different than in our time, turning more often than not into crude and rowdy bacchanals called “ales” in

Chivalry

Manners and gentility did not evolve until relatively late in the Middle Ages. Prior to the emergence of a chivalric code, gluttony was among the most common of vices. The quantity of alcohol consumed was staggering by any standard. At dinner, everyone carved his bit of meat with his own dagger and transported it to his mouth in the fingers of his free hand. The dagger never left the right hand throughout the meal; it was needed in defense against assassination. The reality of dinner-time danger lingers today in two customs. The setting of cutlery on the modern table retains the position of the knife to the right, in easy reach of the hand in which most medieval diners held their weapon. Americans switch hands, grasping the fork in the right hand after they’ve cut their meat. Europeans do not switch, however. They transport the cut portion with the fork held in the left hand and retain, throughout the meal, the grip of the right hand on the knife.

Scraps were not pushed to the side of the plate and placed later into the garbage bin, they were thrown to the floor for the ever-present dogs to fight over. Women were regarded as marginal to existence. The basic fact set the rules: women were physically weaker than men. Hence women were treated, at best, with indifference and, at worst, with brutality and violence.

The emergence of the chivalric code in the twelfth and thirteen centuries brought with it significant improvements in social interaction. The code had its origins in the cult of Mary, the Virgin mother of Jesus, and came to represent the acme of social and moral behavior. Under this value system, the virtuous woman was equated with the Virgin and so warranted respect and protection. The idea never really entirely worked, and the balance of idealization and hormonal drive led to the double standard of behavior that is current today. Chivalry brought with some very fine standards. The ideal knight strove to be virtuous, loyal, brave, generous, truthful, dutiful, and reverent. He was required by code to be kind to the poor and defenseless, to disavow unfair advantage and sordid gain, and, of course, to give his life in defense of his nobleman. Chivalry elevated the status of women to high cult and elevated knighthood to an art form. The love poetry and love chansons of the late Medieval period attest to the new social organization and to the spread of education down the social ladder. Vestiges of chivalry are everywhere today, from the grace of opening a door for another to ideals of fair play in sport and war.

Guido d'Arezzo (d. after 1033) made significant contributions to practical music in his Micrologus (c1025-28). For one, his book contains the first description of a four-line musical staff that permitted accurate pitch notation.

He is also credited with a system of singer's training, known as solfege, which is employed today and which is known by the syllables do re mi. He developed the "Guidonian hand," the naming of the various joints of the hand after the notes. A choir director could use the hand to teach his choir new music quickly, efficiently, and accurately simply by pointing with the index finger of one hand at the appropriate joint of the other.

Another important contribution is his definitive identification of the eight Church Modes, the scales in use in contemporary music. There were four "authentic" and four "plagal" forms. In the authentic forms, the melody ascends from the tonic note and returns to it at the end. In the "hypo" or "plagal" forms, the melody descends from the same tonic note and ascends to it to end. In all, Guido gave eight modes.

Each authentic mode was assigned a name according to its starting note and the pattern of half and whole steps within the octave. The modes and their ranges are given below. [W=whole step, H=half-step]

Phrygian (E-F-G-A-B-C-D-E)

Lydian (F-G-A-B-C-D-E-F)

Mixolydian (G-A-B-C-D-E-F-G)

The Dorian is similar to the modern minor scale except that the sixth degree or note is raised. The Phrygian mode is also similar to the minor scale except the second degree is flatted. The Lydian mode resembles the modern major scale except that its fourth degree is raised. The Mixolydian is like a modern major scale with the seventh degree flatted.

A comparison of Guido's church modes to Ptolemy's tonoi reveals that they are the same scales and same names are used. In Guido's account, however, the names are assigned to different modes that in the tonoi. Ptolemy's Phrygian mode is Guido's Dorian, and so forth. The mismatch demonstrates the educational schism and disruption of the transfer of information from earlier to later times caused by the invasion of the hordes from the central steps of Asia, the ancestors of modern Europeans, and the subsequent fall of

Church canon prohibited changing the notes of the chant that had been codified and standardized through the efforts of Pope Gregory II, Charlemagne, and others. Musically inclined clergy felt their creativity stifled and sought ways to make musical contributions to the liturgy without violating rules. One solution was the trope.

The practice of troping embodied the addition of music, text, or both between lines or at line ends of a chant.

The example that follows gives the textual additions but not the music. Moreover, the example is not an actual trope but nonetheless demonstrates form resulting from the trope process. Here additional material is added before and after the Psalm verse. As noted, chant was sung as a means to enhance texts drawn only from the Book of Psalms. The trope texts invariably furnished additional commentary on the meaniing of the Psalm or "set the stage" for the Psalm.

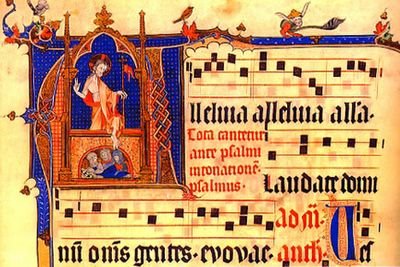

A study of the score reveals that the Psalm does not begin until the marker "Ps" in the fourth line. The Psalm itself is a well known-verse.

The Psalm verse (marked Ps in the score) follows:

Sing ye onto the Lord a new canticle, because he hath done wonderful things.

The ending is the Gloria Patri,:

"Glory be to the Father, Son and to the Holy Spirit."

The letters "E u o u a e" appear at the end of the score and do not form a word. Instead each letter is the first letter of each word of the standard closing formula of the musical portions of the Mass "as it in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end. Amen."

Tropes became more extensive with the passage of time. By the Middle Ages, the trope sections had spun off into a variety of new forms. One particular type of trope, the Alleluia jubilus exerted special influence. In the jubilus, a florid line of new music, or melisma, is sung to the last syllable "a" of the word alleluia.

The strict Church canons against changing chant melodies or text led to the addition of a second (and later third and fourth) line of music below or above the chant melody. The new process, called organum, had profound consequences on Western music, leading to the emergence of rules regulating combinations of simultaneously sounded pitches. These rules are today called harmony. The highly sophisticated system of harmony is a crowning achievement unique to Western music. Only with the global spread of Western influence in recent centuries did harmony become part of the music systems of other cultures.

Despite the inception and rise of polyphony in the ninth century, new monophonic chants continued to be composed. As noted, they were not included in the liturgy proper but used in ancillary worship. A principal composer of new chants as well as sequences was the charismatic Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179). She is the earliest composer to whom a specific body of musical works can be ascribed.

The Rise of Organum and the

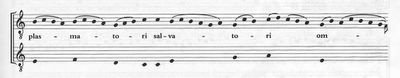

The origin of organum is unknown, but the earliest records of it are found in manuscripts dating from the ninth century. Originally, organum was a type of improvised polyphony in which a second melody was fashioned above or below the melody of the chant. In its earliest form, the two voices moved note against note at the interval of a fourth or fifth.

Parallel organum

Within a short time, the musical texture began to evolve. Each note of the chant melody began to be held longer than its normal value in the original version. The protraction of the time values was described by the French verb tenir, to hold, and from the verb comes the name for the voice that sang the chant, tenor. Around the same time, the tenor was assigned to the lower voice and became known as the cantus firmus, literally “firm melody.” The improvised voice no longer sang note against note with the tenor, but instead featured melismatic passages. Since the improvised higher voice contained many more notes than the chant, care was taken that when notes of the two voices occurred at the same time, they would sing perfect consonances. This use of the chant as the musical basis became the primary compositional method, albeit with significant advances, throughout the period from the twelfth to early seventeenth centuries. Each voice sang the same liturgical text in Latin, though at different rates. The early form of this type of orgaum is called florid organum or Aquitane organum. It has become associated with the St. Martials monastery in Limoges in southwestrn France.The cantus firmus is found as the lower voice in the present example. The cantus firmus is already protracted in comparison to the upper voice. Note that there are now indications of the values of duration for any of the notes.

Aquitane, St. Martial, or florid organum

Two outstanding composers of organum, each working at Notre Dame cathedral in

Chant and its use by Leonin as a cantus firmus

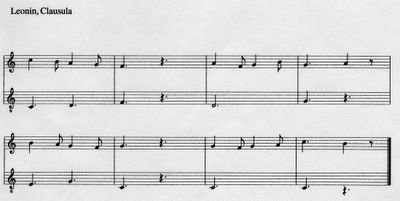

The second composer, Perotin (fl.1180-c1238), was known for his compositions in a newer type of organum, discant. Organum purum and discant differ in the treatment of rhythm. In organum purum, the singers had to take care only that the notes intended to be concurrent were sung at the same time. The slow-moving tenor permitted the quicker moving voice, the vox organalis, to unfold in rhythms not dissimilar to chant. In discant, the tempi of each voice still differed but the rhythm of each voice was closely regulated. To this end, composers borrowed several rhythms from poetry and applied them to music. The system of values was known as the rhythmic modes. Each value of each poetic voice was based in triple meter, that is, each lasted for the duration of three beats. The six rhythmic modes and their values follow. Long values, indicated by L, received two beats; short values, indicated by S received one. Triple longs values, indicated by T, received three beats. All are executed against a three count, or triple meter.

I. Trochee: L S

II. Iamb: S L

III. Dactyl: T S L

IV. Anapest: S L T

V. T T

VI. S S S

One can see a typical application of the rhythmic modes in the present example of discant by Leonin. The upper voice primarily follows the rhythm of the trochee. The lower voice, which contains the cantus firmus (melody of the chant), unfolds in the fifth mode. As noted, the application of the modes permitted easy alighment of the voices and imbued the music with a strong, dancelike, beat.

The rhythmic modes permitted the easy and accurate alignment in time of two or more voices and permitted the voices to move more quickly in relation to each other. Since all the modes are based in triple meter, different modes could be simultaneously used in different voices. Modes I and V were the most common and. in a two-voice texture that features these modes, the upper voice would express a L-S combination for every T in the cantus firmus below it.

Each section could be based in a different phrase of the cantus firmus. When the chant was exhausted, composers simply began the cantus firmus again or reused some portion of it. The upper voices of the purum and discant sections were newly composed, and each purum section and each discant section differed musically from earlier or later ones, even if the same phrase of the chant were used as the cantus firmus for more than one section. Composers, especially Perotin, began to compose substitute discants, that is, use the cantus firmus from an existing discant and compose new music for the upper voices. The new discant often substituted for the original one. The practice also prompted musicians and listeners alike to begin to regard the discant as an independent or free-standing composition.

Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris

Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris

<< Home