The Ars Nova and the Transition to the Renaissance

Significant strides in musical notation in the thirteenth century, ascribed to Franco of Cologne, permitted the indication in score of even finer and more independent rhythmic ideas than the system of rhythmic modes could accommodate. Modern concepts of meter have their origins in Franconian notation. Even greater strides, strides that would spell the end of the rhythmic modes, were made in the fourteenth century.

The movement derives its name, Ars nova, from the last sentence of a treatise by Philippe de Vitry (1291-1361). Ars nova, "New Art," came to denote the style of French music in the first half of the fourteenth century. The movement's contributions were twofold. The first concerned the acceptance on an equal footing of duple meter (regular groupings of two or four beats) alongside the traditional triple meter of the rhythmic modes. Although duple meter would seem more "perfect" to the modern mind because it is easily divisible into halves, the association of triple meter with the symbol of the Trinity, the "Father, Son, and Holy Spirit," generated resistance.

The second contribution concerned the inevitable division of the standard written note durations into increasingly shorter values. In modern terms, if the whole note equals four beats in duration, it can be divided into two notes of two beats each called half notes. The half note can in turn be divided into smaller units, yielding two notes of a single beat each called quarter notes. The quarter note can also be divided into two notes of half-beat durations called eighth notes. Triple divisions are also possible. For example, a half note, usually two beats, could be divided into thirds. The symbol for the quarter note would still appear to express the division, but the number "3" would be written above the group of three quarter notes to indicate the irregularity.Isorhythm

The interest of Ars nova composers in the articulation of vastly different rhythmic and metric values also extended to the use of rhythm to plan and control with uniformity an entire composition. Isorhythm was a compositional technique that evolved to meet this need. Isorhythm contained two components, the talea and the color. The talea was a rhythmic pattern that was chosen and repeated throughout the piece. Similarly, the color was a set of notes treated in the same way. Although isorhythm was usually applied to the cantus firmus, it could also be used in other voices.

In composing, the notes of a cantus firmus could supply the color and a rhythm chosen to sing the notes. Upon repetition of the cantus firmus, the duration of the notes could be changed relative to the first statement but not relative to each other. If one sings do-re-mi-fa-mi-re-do and assigns four beats to each note, the talea and the color are established. If one sings the same notes but holds each note twice as long, then the talea has been modified isorhythmically. Here the ratios of duration from one note to the next have remained the same. The device is useful as a unifying element to the sections of the music, since each statement resembles the other, and avoids literal repetition of the material in the isorhythmic voice. Isorhythm is extremely subtle and often revealed by study of the score rather than by hearing. A principal composer who used the technique was Machaut.

Formes fixes

The formes fixes were used in song composition and were derived from contemporary poetic forms. The formes fixes featured repetition of both musical lines and some lines of text. New content was given as the music progressed, but each new verse of text was sung to one of the two lines of music already presented. To exemplify, the schemas of two of the formes fixes follow, the virelai and the rondeau. A third important form, the ballade, followed the scheme AAB. The primary chanson form in

The letters indicate different lines of music. Capital letters indicate that the text has not changed and the numbers that follow give the poetic line. In the example of the virelai, the "A" indicates a refrain, that is, the same line of music and the same text.

In the example of the rondeau, the A B sections that begin and end the form are the refrains. A partial refrain occurs at midpoint.

John Dunstable, an Englishman working in

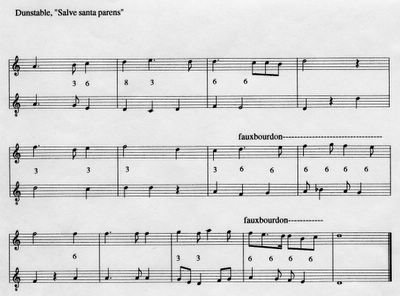

John Dunstable, "Salve sancta aperns"

The adoption of these consonances by Burgundian composers Guillaume Dufay and Giles Binchois and the later Franco-Flemish composer Johannes Ockegham, set the stage for the evolution of a new musical entity, the chord. [A chord is formed when intervals of the third are stacked above a note. For example, a C chord results when an E note (C-E=3rd) and a G note (E-G=3rd) are sounded above a C note. The C note is called the root and lends its name to the chord]. A sixth results when the interval of a third is inverted. In this process, the lower note is moved an octave higher so that C below-E above becomes E below-C above].

(Right click to better view the image).

Dufay, Gloria from "Si la face ai pale"

When studying the score, consider that the "8" that appears below the clef sign on the second system indicates that the line is an octave lower than written Hence when counting the sixth actually counts out visually as a third and vice-versa.The fifteenth-century composer recognized that thirds and sixths added a sweetness to the music that was lacking in compositions from earlier centuries, yet did not recognize, as we do today, stacked thirds as entities containing specific identities and specific functions. Vestiges of fauxbourdon abound in modern music, particularly the popular song.

Fauxbourdon Vestiges in 16th Century Lute Music

<< Home