Medieval Christian Art: Vestiges of Earlier Times

Ancient Formal Elements

Several characteristics from ancient art are notable. In Egyptian bas relief, the artist did not portray the human figure naturalistically. Instead he depicted each part of the body from its most definitive view. Legs and arms were shown from the side view while the trunk was viewed from a full-frontal vantage point. No attempt was made to create a sense of depth of field, or illusion of "foreground-background" relationship. Here the artist worked from what he knew, not what he saw. The result was an idealized abstraction of human form, an icon whose parts reaffirmed and validated the Egyptian concept of the body. Other figures, such as birds, were similarly reduced, condensed, and abstracted. The Egyptian artist did not concern himself with relative proportions.

Portrait Panel of Hesy-ra, from Saqqara, c2650 B.C., example of Egyptian bas relief

The abstraction of form in Egyptian bas relief did not carry over into Greek or Roman painting or sculpture. The aim of the Greeks was clearly the visual celebration, not cerebration, of the beauty, power, and drama of the human body. Naturalistic rendering better suited their purpose. Whereas the Greeks portrayed gods and atheletes, the Romans built upon the Greek style by adding specific identities to their busts.

"Portrait of a Roman," dated c80 B.C.

The different needs for meaning of each society determined, of course, the nature of the realization. For the Egyptians, the figuration represented man on a fundamental level, a kind of self-validation of order. For the Greeks, the figuration offered a model of beauty and power. The embrace of beauty was far more than just sensual. The figuration conveyed visually the standard of physical conditioning to which each citizen should aspire, a physical prowess absolutely essential to survival in a world of city-states and empire-building. The Roman addition of the facial features of leaders aggrandized these leaders and helped to institutionalize them in a state larger than life.

The Market Gate from Miletus, example of Roman gate, c160 A.D.

European Christian Application: Changes in Symbollic Meaning

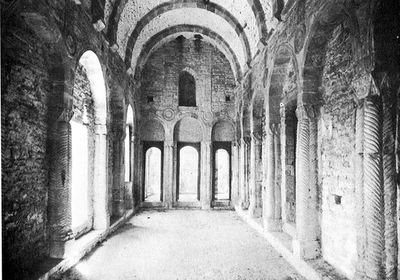

The significance of the arch as a portal is paramount to understanding its meaning in the Christian belief system. One enters the church, "God's house," through the portal of the arch. Inside the ceiling might consist of a tunnel created by extending arch in its depth. The altar itself is framed by another arch, and the portal created by this arch over the altar is the one that leads through true belief to the afterlife. On a side note, the most churches, then and now, have the cross as the footprint of their floor plans.

Santa Maria de Naranco, completed 848, exterior view

Santa Maria de Naranco, interior view

The two architectural examples presented here, one Carolingen, the other Gothic, are separated in time by three hundred years. Another architectural style, Ottonian, enjoyed currency in the intervening centuries. All three styles display the features described above, the arch of Roman might now imbued with the meaning of God's omnipotence and promise.

Chartres Cathedral

Between the time of the rule of Charlemagne in the ninth century and the high Gothic in the fourteenth, cathedrals grew dramatically in size and height. The cathedral played a special role in the religious and economic life of the Medieval community. The grand dimensions of the cathedral far exceeded any structure a layman could build. Once inside the front arched portal, the parishioner entered an "other-world." This "other-world" was filled with magnificent and expensive religious art, unusual light effects, sophisticated and ethereal music, "true" relics, and mysterious ritual. In brief, the rituals of belief inspired in the faithful a sense of spirituality, piety, and awe, and this emotional state was bolstered mightly by architecture on a scale so grand that it was difficult for the peasant layman to apprehend.

The cathedral could also add considerable monies to town coffers that relied primarily on aggrarian earnings. The cathedral became a source of revenue when it assumed significance as the destination point of religious pilgirmage. Size, aesthetics, music quality, and the quantity of sacred objects, such as relics, figured prominently in the success of the cathedral in attracting tourists.

The development of the flying buttress (see exterior view of Notre Dame in "Rise of Organum") permitted new architectural features. The buttresses absorded the load of the roof and diverted it outward, eliminating the need for the thick, heavy walls of earlier structures. Not only were thinner walls and considerably higher roofs made possible, but large areas of the wall could be replaced by stained-glass windows. The stained-glass windows profoundly improved the interior aesthetics. Earlier cathedrals had relatively lower ceilings. Their thick walls could safely accomodate only small windows. Inside, then, these structures were dark and gloomy. The high ceiling of the Gothic cathedral was itself a stunning achievement, and now the windows allowed multicolored light to set the vast interior space awash with light.

Chartres Cathedral, view of upper gallery windows

Moreover, the stained-glass windows fulfilled another critical function. The typical parishioner was illiterate. The windows were used to educate, and the scenes portrayed in the window designs were intentionally drawn from the Bible. The window designs themselves incorporated hundreds of shards of geometrically-shaped glass joined together at the ends by strips of lead. Similarly, the scenes were filled with abstract figures, recognizable in their identities by their activity, but not developed, as in ancient Greek or later Renaissance, Baroque and Romantic art, for their realism or beauty of human form. In a final but dangerous point, at least for this author, is the casual and unresearched suggestion that the halo and the Roman arch are not so disimilar.

Chartres Cathedral, detail depicting the "Death of the Virgin"

Not surprisingly, the arch and abstracted figuration found in Medieval architecture and stained-glass windows are also the prinicipal components in the art that adorned religious manuscripts of the period. All material items were made by hand. Books were copied by hand by monks in the monasteries for use in-house or by the literate members of the ruling families. Religious messages supplemental to the text could be conveyed in a variety of ways that also greatly enhanced the beauty and value of a manuscript. One common means, manuscript illumination, was the pictorial decoration of the first letter of the first word on a page. Another means involved scenes on the covers. Bookcovers were often carved from ivory or made from precious metals and studded with gemstones. The eqaution of power and wealth is a very old one.

The examples that follow span four hundred years, yet they all share common characteristics. One would expect to see some change in the artwork over so long a period of time. Indeed, if one visually ordered the examples on the basis of "evolution," the "Vespasian Psalter," the crudest realiztion of the set, would be placed first and the "Lorsch Gospels," the most naturalistic rendering, would be placed last. Different artisans in different regions worked to their own sensibilities, guided foremost by the tenet that the image must express a meaning that teaches, reminds, or reaffirms.

The Medieval world, then, was one ruled by symbols. Symbols pervaded every aspect of life and assumed a critical role. To moderns, the orientation toward symbology reveals a fundamental aspect of Medieval man's view of life. He lived outside the suffering of his everyday reality. He would be relieved in the afterlife and, in the meantime, he could glimpse the world to come in the intellectual, intermediate world created by the icons and signs that surrounded him.

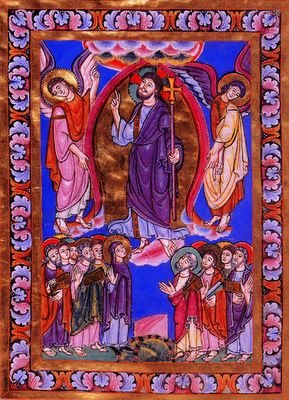

As noted, the following manuscript illuminations have common elements. All of the examples are narrative in nature. The arch appears in some form in each example. There is no development of spatial relation within the field, that is, there is no effort to create the effect of "foreground-background." Although differing degrees of realism are found among the renderings of human form, all of them are essentially abstract. The characters are recognized by the scenes in which they are immersed or by ancilary features such as objects that a figure might hold. The open book, for example, was the symbol for the teacher. The degree of abstraction is apparent, even in the more naturalistic figuration of the Lorsch Gospels, in that the folds of the clothing define the body, not vice-versa. As in Egyptian art, scale is not important.

Gospel of St. Matthew, manuscript illumination

Lorsch Book Cover, Ivory, c810 (Museo Sacro, Vatican, Rome)

Vespasian Psalter (British Museum Cotton MS Vespian A, England, Canterbury, c800). David, Traditional Author of the Psalms with his Musicians

Gospel Lectionary (British Museum Egerton MS 809, Swabia, possibly Hirsau, c1100). The Ascension

Salvin Hours (British Museum Add. MS 48985, England Lincoln, possibly Oxford, c1270). Christ Before Pilate

The "Madonna in Majesty" is a painting. The gold paint contains real gold. Here the arch is abstracted into a point (review the interior view of Chartres Cathedral, above), but the flat field and abstracted figuration of earlier manuscript illuminations are still intentionally present.

Cimabue, Madonna in Majesty (Louvre, Paris; executed originally c1295-1300 for Church of St. Francis, Pisa, taken to France by Napoleon as spoils of war)

The Arch in Later Times

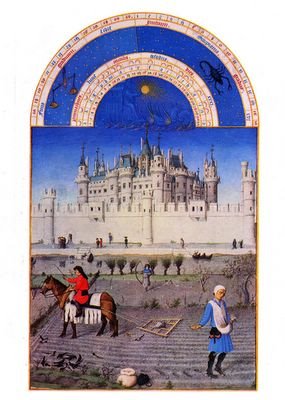

The subsequent examples date from the late Middle Ages and reflect the discoveries of perspective of Giotto (see Kamien). Curiously, the mathematics (geometry) that made the realization of perspective in art possible had been in place since the second century. "October" hints at the radical shift in art and society that Humanism (see "Humanism" in Renaissance Lectures) would shortly bring.

First, there is the perspective. The figures, though not well-developed by Renaissance standards (the clothing defines the body), make meaningful strides forward in gestures that are representative but also possess elements of realistic depiction. The figure on the right is sowing seeds for a winter crop, and the viewer can almost see the motion of his arm. Unlike the earlier images, this sower is not static.

Like the paintings to follow, however, the gesture conveys an activity of grace and refinement, not one of hot, tiring, dirty labor. The world in which this activity unfolds is one of tranquillity and purity, a significant shift in social attitudes since this world of tranquillity is earthly. Moreover, the Roman arch, by this time more a Christian symbol than an Imperial one, is interpreted in terms of the Zodiac. This arch, then, is not a portal to the Christian afterlife, but one to some small patch of peace, well-being, and relief on earth.

Limbourg Brothers. "October" from Les Tres riches <>heures du Duc de Berry, (1413-16)

"Madonna with Child and Saints" offers a curious study. First, the painting features perspective, but its execution is not convincing. The viewer sees three distinct fields instead of a graduated foreshortening that geometrically recedes into the horizon. The saints occupy the first plane, and the Madonna and Child define a second. personal plane not shared by any other figuration. The Roman arch, present in its most classic reiteration, is actually the agent of perspective.

Each of the figures holds a gesture, but only the second figure from the left expresses a "body language" that is dynamic or believable. The eye is drean to this figure instead of to the Madonna and Child, the supposed central figure. In part, the veiwer's eye is drawn to him because he wears fewer clothes than the other figures but, more importantly, because the his posture displays a natural relaxation and an element of motion.

Domenico Veneziano, Madonna and Child with Saints, c1445, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

The final examples date from the reign of Louis XIV, the "Sun King," of

Under Napoleon, classical formalism would continue to be nourished. The ancient symbols would transfer to him as Emperor. Indeed, he would fill

Versailles, late seventeenth century, interior view of chapel

"Salon d'or" in the Paris house of Comte de Toulouse, late seventeenth century (now Banque de France)

<< Home