African Influences in the Popular Music of the United States

The first African immigrants arrived at Jamestown in 1619. Initially, their relationship to the white English settlers was one of semi-free indentured servants. African servants were treated humanly and regarded by their early masters as a part of the family. Acculturation of the African to European customs was rapid in part because white and black worked side by side on a roughly equal footing and because the African was part of a very small minority of the overall population.

American slave ownership was not extensive in the first century. In 1624, the total slave population of Virginia was twenty-two. By 1640, there were one hundred-fifty slaves. By 1649, the number had grown to three hundred among a population of fifteen thousand whites. Ratios of the white population varied from 25:1 to 5:1 depending upon region, with the coastal areas such as the Sea Islands of South Carolina having greater numbers among the African population. In areas with high concentrations of blacks, African culture survived far longer.

The numbers of slaves dramatically increased in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as the plantation system became the agrarian equivalent of the large corporation. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 turned around the sagging economy of the South and ensured the establishment of the cotton-based plantation system. More and more slaves, essentially chattel labor, were needed to make the plantation profitable.

The slave trade was abolished in 1808, though slavery did not legally end in the United States until Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (1863) during the Civil War. By 1860, the number of African slaves in the United States was 4,441,830.

African culture changed radically during this period. For one, the end of the slave trade meant that African culture was not reinforced or reinvigorated by new arrivals from Africa. Moreover, the majority of this group had been born in the United States, and their concept of “African” was based upon songs and stories handed down from their parents and grandparents. Hence the culture of the slave increasingly became a hybrid of African and European, as did that of the white master.

Pathways from Africa to the New World

The majority of the slaves came from West Africa and a geographical area that extends on the west side of the continent from West Africa southward to the lowest tip. They came from a large variety of tribes with a great diversity of customs. A partial list of the the tribes includes, moving from north to south, Wollofs and Malinkes (19%), Mandingos and Ashantes(11%), Yorubas (16%), Hausas, Ibos, and Sekes (27%), Bakongos and Mbundus (25%), with a miscellaneous final 2% snatched from the east coast of Angola.

The Caribbean islands served as home for some unfortunate Africans, and a “seasoning” ground for all. Those who remained in the islands worked in the fields, most notably in the growing of a second New World “gold,” sugar cane. All slaves underwent a period of “socialization” and standardization before being sent to work in the fields, whether on a Caribbean island, in the United States, or in the countries of South America that ring the Caribbean. The slave newly arrived in the islands was a representative of one of the manifold tribal groups. He not only had to be introduced to the language of his master (English, Spanish, Portuguese, etc.) and be forced to accept the expectations and realities of his new life, but also had to be reconciled with the customs and languages of other slaves from other tribal groups and regions. The slave population on the Caribbean islands invariably outnumbered the white population. As a consequence, aspects of African culture remained quite intact for a far longer period than on the mainland.

Among all African groups, several commonalities existed with regards to music. Music was an integral part of life and was regarded as a celebration to be shared and made by all members according to his tastes and abilities. Activities crucial to survival, such as sowing, harvest, and hunting, were accompanied by music, as well as the recreations contingent to the activities. Cultural cohesion was also a critical function of music, and tribal history and social information was transmitted from one generation to the next through songs and even dance. Music emerged that suited the circumstance, gender, age, status, and occasion. The community created among Africans by the participation of all members in singing, dancing, and drumming stands in sharp contrast to European attitudes toward music. That European music was irrevocably linked to the Church for the first 1500 years is evident in the quiet and respectful deportment of the modern classical concertgoer. African music, with its emphasis on melodic improvisation and the use of sophisticated rhythms played on a wide variety of percussion instruments shares very strong similarities to Arab and Indian music.

Early Musical Acculturation of the Slave in the United States

As noted, the African worker in the New World in the seventeenth century was absorbed rapidly into the prevailing European culture. During this time, he learned to play European instruments, especially the violin, but also the French horn, the flute, the trumpet, the fife, and the variety of European military instruments. By the mid-eighteenth century, black fiddlers routinely began to supply the music for dancing and other casual entertainments, both white and black. Since the written recording of African American music did not begin until the mid-nineteenth century, we do not know exactly what music the black fiddler played on the fiddle but is not unlikely that he reproduced African music and altered European tunes to suit. By the mid-eighteenth century, however, jigs by black fiddlers were common in the repertory. By 1734, a slave’s musical prowess became a significant aspect of his identity, and the description of his musical ability was included in the “wanted” poster. Most black fiddlers, regardless of the time period, were “ear players,” not trained, reading musicians except perhaps in New Orleans.

Not all instruments played in the New World by slaves were European ones favored by the masters. Slaves fashioned their own drums, of course, but also reproduced facsimiles of instruments they had know in Africa. One of these, the balafo, is a variant of the xylophone. The different pitches are determined by the length of the wooden slats, and the gourds underneath each slat acts as a resonating chamber. Other improvised instruments included the “bones,” which were really animal bones struck together, the triangle, and the tambourine. The tambourine might very well be a hybrid of the drum and the banjo.

Balafo

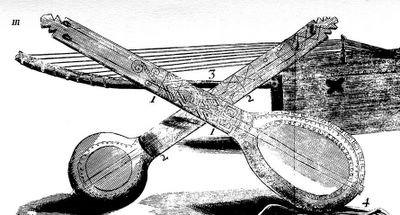

Another important instrument is one many Americans believe is American: the banjo. In fact, slaves first fashioned necked-string instruments after ones in Africa. These instruments closely resemble the Arab lute (see the European lute featured in my introduction—it too was derived from the Arab equivalent). The resemblance of this forerunner is not surprising when one takes stock that many slaves came from areas of Africa that were heavily influenced by Arab culture. The earliest written mention of the banjo occurred in 1621 in the journal of a white trader in Gambia. In the New World, most written references to the banjo, written between 1678 and 1740, occurred in the historical accounts of Jamaica and Martinique by British and French scholars. The written mention in America dates from 1754, in an advertisement for slaves in the Maryland Gazette. Throughout its life the banjo went by a range of names including banza, strum-strum, espece de guitarre, bangil, banjer, banshaw, merry-wang, bandore, bonjour, banjah, violon des Negres, banjay, banjaw, bonja, banjoe, bongau, bonjaw, and bangoe, in case you are interested.

In the foreground, early banjos that resemble Arab and Indian musical instruments

Dancing was a critical component of the social lives of both the African American and the white master. As noted, African dancing, in the form of the "black" jig, had found acceptance by the mid-eighteenth century in formal white circles. Two illustrations follow that depict slave dance scenes and the instruments used to make the music.

Slave Dance featuring European and African Instruments. Pictured are the European fiddle, the lute-like banjo, and the bones. Note the Europeanized dress. The sketch was made in Virginia in 1853.

<< Home