Modern Jazz

Count Basie

Significant changes occurred in their music. Pianist “Count” Basie opened the texture of jazz by eliminating the every-beat strum of the chord player (guitar or piano). Instead, Basie staggered the chords he played, “stabbing” in little groupings so that the highest notes of the chords he did play created melodic motives. The elimination of the chord on each beat also gave the soloist an open musical texture in which to experiment. The style of chord-playing is called “comping,” fittingly shortened, like the style of playing, from the word “accompanying.” The shift in accompanying style also eliminated at rhythm-section trademark of Swing, the "wump wump wump" of the strummed guitar.

Another important feature of Basie's soloing style was his economy, a characteristic entirely consistent with his style of accompanying. Basie was not afraid of the pregnant pause created by the silence between phrases of the melody. His melodies were always carefully constructed, each note having been considered for its value, meaning, and role in the context of the overall phrase.

Count Basie

New Kinds of Melody: Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young

While Basie's new "comping" became a critical feature of the new style, his contemporaries (and often band members) worked to develop new phrasing. Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young, two of the most significant saxophone players of the era, began to develop a new concept of melody. Instead of rifts, they began playing extended, unbroken melodies. The important notes of his melodies fell more often on accented beats than those of blues and swing, but the African American component was still evident in the rhythmically unusual stopping and starting points. These new, long melodies often seemed breathless, extending sometimes through nearly the entire stanza! Both musicians were alumni of the Kansas City scene as well as, later, the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra (big band). While the new style of phrasing won critical praise, it did not suit well the Swing rift sensibilities of Henderson, who regarded especially Young's playing as reckless and eccentric.

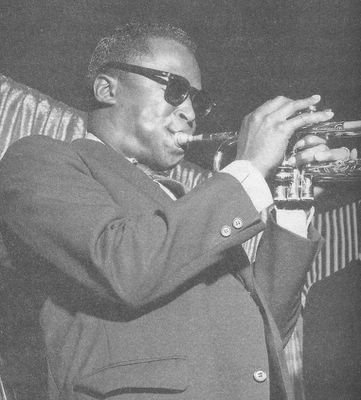

Lester Young

As the big band lost the economic support it required to survive, many musicians, including those based in Kansas City, began to follow the lead of "jump" bands such as those maintained by Louis Jordan. These bands retained essentially the same instrumentation, but not the same number of personnel. All doublings were eliminated so that only one instrument of each type remained. When finished, the new "combos" were very similar to those found in Louis Armstrong's "hot" recordings except that the rhythm section of the Swing band, not the New Orleans band, was preferred. Hence the combo line-up featured a rhythm section of drums and bass. The guitar was sometimes included, but more often the more flexible piano took its place. The better was better suited to function as both a rhythm (chordal) and solo instrument (melody) and, more importantly, did not have problems playing in the difficult flat keys that suited the instruments of the front line. The front line of the combo consisted of saxophone and trumpet. The flute found occasional work in these bands, but not in Kansas City or in East Coast jazz. The presence of the flute is almost always a dead giveaway that the music was very late in the period, potentially included as part of a more commerical "jazz" recording, and recorded in sunny California.

Classical Music Influences on Modern Jazz Harmony

Late nineteenth and early twentieth-century music devleoped along different lines than American music of the same time period. The reasons for diferent lines of evolution were largely cultural. The African-American influence and the "melting pot" character of America juxtaposed music form a large variety of cultures. The accommodation of these different musical styles and their fusion into a single style occupied American musicians.

By contrast, Europe retained a more homogeneous character to its culture, and its musical evolution did not center on an infusion of new ideas from other cultures, particularly African, but simply continued a line of unbroken growth from its earliest days. The central issue for European musicians was finding ways to deal with a tonal system that was running out of possible note combinations. With the exception of the music of Igor Stravinsky, the meters and rhtyhms of European music changed little from one century to the next.

Modern classical music sought solutions by experimenting in different directions. In the late nineteenth century and the first few years of the twentieth, French "Impressionist" composers such as Claude Debussy experimented with the effects that unusual harmonic progressions could create, and these experiments often resulted in "atmospheric" effects, as in "L'Apres midi d'une faune" ("Afternoon of a Faun"). His music was melodically built up of short motives, a similar device to later Swing jazz. He never sought to venture from the ideal of beauty but rather reacted to the overbearingly grand and serious character of Germanic music traditions, especially those embodied by the heavy operas of Wagner. Debussy explored both the orchestra and the solo piano for new timbres and new means to lay out chord progressions that were at once beautiful, refreshing, and coherent. These experiments had a profound effect on modern jazz men, especially from Charlie Parker onward.

A second area of exploration was offered by French Impressionist Maurice Ravel. Ravel also sought relief from German music, leading him to explore orchestration and the ressurrected use of older scales,or modes. The scales he chose were used first in Church music, in particular, chant, and enjoyed the greatest currency between the ninth and sixteenth centuries. Each mode has a name and a characteristic sound. In Bolero, the second section of the musical example, the section that sounds "Spanish" or "Arab," is actually the Phrygian Church mode. Jazz players and teachers use these Medieval Church modes to this day in both improvisation and educating younger players.

Significant strides in both tonality and rhythm (in European music) were made by one of the most important classical composers of the first half of the twentieth century, Igor Stravinsky. Stravinsky was a Russian emigre to Paris, where he workd composing music for the Ballet Russe. His collegues included some of the most important composers (i.e. Ravel) and artists fo the period. His friendship with Pablo Picasso and Picasso's interest in African art which resulted in Cubism led him to develop a curiosity about African music and African-American music. Stravinsky was able to hear African music first hand at the frequent African expositions mounted at the time in Paris (remember that France's colonial holdings were and are in Africa). He could not hear jazz in France, but Sergei Diaghilev, the impresario responsible for the success of the Ballet Russe brought back ragtime scores for Stravinsky each time business took him to America.

The influences become apparent in two areas: polytonality and polyrhythm. The audio first example demonstrates Stravinsky's polytonal thinking. Polytonality is effected when the musicians play simultaneoulsy in two different keys, as in the first audio excerpt from "Le Sacre du printemps" ("The Rite of Spring")! The impact on later American jazz would be heard in the acceptance of greater tonal experimentation and especially in the consideration of formerly dissonant sounds as consonant ones. Beginning with Parker, jazz musicians began to fashion solos that embraced not the key of the music of the accompaniment, but the music of a key a third, fourth, or fifth higher. The process works because each of the applied keys shares a significant number of notes with the other key sounded.

Stravinsky's polyrhythmic experiments were likely prompted by firsthand experience but somewhat guided by the handling of polyrhythmic concepts in American music. American musicians had far more extensive experience with polyrhythm, having first encountered it in African drumming. Much of the history of American music involves the modification and absorption of polyrhythm into its mainstream. The result of the adaptation is seen, oof course, in the presence of syncopation of the majority of American music styles. Nonetheless, Stravinsky's efforts are worth a listen. The second audio file demonstrates "additive" rhythm. In "additive" rhythm, each successive measure is expanded by one beat so that the count might be 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 5, etc. The effect is one of syncopation but also one of "chugging."

A final radical approach is found in the early music of Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg believed that tonal music had no more possiblities to offer, that it was finally depleted of its ability to create new music or even to renew itself. His appraoch was one in which all tonal references were avoided. In brief, he fashioned melodies that gave to signal as to beginning, middle, end, or even key. The accompaniment was handled in the same way, with the intent that nothing familiar would exist in his music and that the listener would be forced to make new associations as in "Mondestrunken" ("Moon-drunk").

These European developments had a profound impact on modern jazz, though they were invariably filtered through American, and especially African-American sensibilites. Jazz musicians did not hide the fact that they sought new ideas in Europe's music, a music they heard first as soldiers in World War I. World War I also opened direct opportunities for black jazz musicians. Europeans, and in particular the French, heard this music and embraced it. Paris offered employment and succor to many black jazzmen who felt unwelcome at home, even through both wars and most of the twentieth century.

Suggested Listening:

Claude Debussy, "L'Apres midi d'une faune"

Marurice Ravel, "Bolero"

Igor Stravinsky, excerpts from "Le Sacre du printemps"

Arnold Schoenberg, "Mondestrunken" from Pierrot Lunaire

The New Style: 'Modern' Jazz of Parker and Gillespie

One of the two most important musicians of the period was saxophonist Charlie "Bird" Parker. Parker studied the records of Hawkins and especially Lester Young and learned the basic tenets of their new approach to soloing. He would later expand the approach into a new style, “bebop” or just “bop.” He retained the long lines and the unusual starting and stopping points, but added two features. First, Parker played the music at tempi that most of his contemporaries could not follow.

Second, although the blues remained a constant feature, songs that did not follow the twelve-bar progression were approached differently than in earlier jazz. In Parker's approach, not only did the tempo fly, but the rate of harmonic change (the rate of changes from one chord to the next) also dramatically increased. In a Swing piece, then, a chord might be sustained through several measures; in Bop, it was customary to play two chords in a single measure! Moreover, Parker used French Impressionist music, especially that of Claude Debussy, as a harmonic model. He began to incorporate unusual chord progressions, often moving from one chord to another chromatically and, in the process, stepping out of key for a measure before returning to the original key. The same chord progression as it might appear at the end of the stanza in a Swing tune and in a Bop tune are contrasted. The chord patterns graphed below are found on two audio files. The numbers in parentheses represent the duration of the chord in beats. The first files gives the chord progressions only. The second furnishes the proessions with a lead overlaid. Notice that the second lead, like the chords that support it, goes in and out of key with each successive set of chord changes. Improvising over bop progressions presents very speical challenges (or opportunities if you paly really well), a hard fact that many Swing players who could not make the cut discovered in the day.

Swing: Bm7(4)-E7(4)-Am7(4)-D7(4)-G(4)

Bop: Bm7(2)-E7(2)-B flat m7(2)-E flat7 (2)-Am7(2)-D7(2)-G(4)

The same chords found in the Swing tune remain as the superstructure, but in the Bop version chromatically determined chords are interpolated. The melody improvised over the Swing tune could not remain the same in the Bop rendering--the soloist had not choice but to change keys with each new chromatic pair of chords! The new chromatic feature was part of neither Hawkin's nor Young's music, but an modification by Parker. The scope of Parker's abilities is brought into even sharper focus when one considers the incredibly fast tempi at which he insisted the band play! Parker's new style assured exclusivity, and only the finest musicians of the day could, when they played with him, keep up.

An important social feature of Bop was the sense among its creators of alienation from the musical mainstream. Part of this view was the result of the failing music economy of the big band, but also a product of what Parker and his contemporaries regarded as a compromise and prostitution of musical art in order to sell music. Racial overtones were also doubtless present, though Parker did not make racial distinctions among his musical colleagues. Race did not enter into his choice of musicians, only ability.

Parker and Young later became friends and musical colleagues. Both playing styles of both Hawkins and Young changed to keep up with the new development of the very style they started! Young remained active as a player, but Hawkins retired in the 1960s from all but occasional public performances.

Charlie Parker ("Bird")

The other important Bop musician was trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Gillespie was not born in Missouri but in rural South Carolina. He grew up in abject poverty, the youngest of nine children. He taught himself to play the trumpet at age 12, by his late teens was working as a full time musician. His first significant job came playing with Cab Calloway's group, who shortly put him out on the street for his thoroughly modern and unorthodox approach to solo improvisation. Calloway rather unaffectionately called Gillespie's playing "Chinese music."

Gillespie's music models for his phrasing were the saxophonists of the day, and his understanding of Bop harmony came from Parker, who he soon harmonically superseded. Gillespie also developed his skills as a scat singer and, with his horn-rimmed glasses and ever-present beret, cultivated an image as an eccentric artist. The most significant visual trademark, however, was his trumpet, which had been bent in an accident. Gillespie liked the sound and continued to play that particular horn, with its upward-directed bell.

Unlike Parker, who had tendencies of self-absorption due to addiction and a slightly anti-social streak, Gillespie enthusiastically tutored and encouraged the next generation of Bop players, including the likes of Miles Davis. Gillespie's later embrace and promotion of Afro-Cuban music likely had an impact on both Davis' musical experiments and his ultimate move from jazz to Fusion. Gillespie and Parker were friends and on-stage rivals, and played together in New York off and on throughout Parker’s short, troubled life. More importantly, they intellectually fed each other new ideas.

Miles and “Cool”

Miles Davis was, like Parker, a native of Missouri. Unlike Parker and Gillespie, he came from an upper middle class family (his father was an oral surgeon). He enrolled at Julliard and lasted only a few months because, instead of attending to his studies, Davis prowled the nightclubs to play with the bop musicians he found there. He finally found Charlie Parker, and the latter immediately took him under wing. Jazz historians have noted the differences in style between the two musicians, but more than one historian commented that Parker might have recognized the future of jazz in Davis.

Miles Davis

Early in his New York City career, Davis conformed to mainstream Bop. There he had an opportunity to play with and learn from the most importatn players of the day. These included not only Parker, his mentor, but the more experimental Dizzy Gillespie. As noted, Gillespie found a strong attraction in the Afro-Cuban rhythms of rumba and its layered percussion, and perhaps saw in the music new directions jazz could take when Bop had expended itself. The revelation and the experimentation could not have been lost on Davis who, himself, would later take similar steps in his musical evolution.

Once Charlie Parker, the driving force of Bop had died in the early fifties, the style began to wind down. Bop, as dynamic as it was, also had very clearly and narrowly defined parameters. These parameters insured full exploration and development of the style would occur in a very short time. Davis’ first musical breakthrough was a stylistic evolution that retained most of the features of bop—the pared-down combo, the same instrumentation, the open texture of “comping,” and the long bop lines--but changed the approach.

His new music, called "Cool" jazz, eliminated the both the blistering tempi of Bop and the rapid fire rate of harmonic change. The progressions that underpinned music of this period often consisted of only a few chords, and each of these chords was sustained for very long durations.

In the Swing tune, a chord might be sustained for measure or for several measures. In Bop, the chords often changed every two beats. In Cool jazz, a chord might sustain for eight or more measures! Unlike Swing and like Bop, the chords that underpinned Miles' Cool compositions were often chromatically related. For example, an entire stanza might consist of eight measures of an A7 chord followed by eight of a G7 chord. The two chords are not in the same key.

The resulting effect is a broad musical canvas that unfolds in a "laid-back," unhurried rate. The breadth of the music, that is, that the music remains on a single chord for a protracted time span, permitted the soloist to more extensively explore not only the standard scales of the key, but to experiment with unusual nonstandard scales derived from other time periods and other cultures. Among the favorite scales were the Church modes, the scales used in Medieval times as the basis of chant! Miles developed Cool jazz away from the New York orbit, largely on the West Coast, where Davis moved as the bop movement ground to a halt. Once the Cool style had been exhausted, Miles declared that "jazz is dead." He moved on to other hybridizations created, for example, by combining jazz and rock.

Other Important Modern Jazz Musicians

Two other musicians figure prominently in the modern jazz movement, and they are Thelonius Monk and John Coltrane.

Thelonius Monk

Thelonius Monk was born in North Carolina, but he grew up in New York City. His earliest musical experiences involved Church music and, as a teen, he toured as pianist with an Evangelist group and played church organ. His interests soon turned to jazz, and he was hired as house pianist in the early 1940s at the legendary jazz club, Minton's Playhouse. The work brought him into close contact with the most important musicians of the day including Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Rollins, Milt Jackson, Miles Davis, and John Coltrane. Monk made his first recordings around 1944 as sideman to Coleman Hawkins and his first recordings as a bandleader in 1947.

Monk developed a highly personal and syncopated style of solo piano playing that overlapped and complemented but did not wholly embrace Bop. His career was derailed on two occasions by problems with the law. Both involved narcotics that were found in cars in which he was riding but which did not belong to him. The first arrest resulted in the suspension of his cabaret license, the all-critical card to musicians working in any place where alcohol was served. The second resulted in police brutality. The severe beating with a blackjack resulted in little more than a dismissal of charges. Despite setbacks, Monk rose to international prominence through his live performances and recordings, reaching the apogee in Carnegie Hall concerts and a feature on the cover of Time magazine.

Monk had the reputation in later years as an eccentric. His style of dress--the dark wuit and the sunglasses--became the standard uniform of jazzmen and the iconic stuff of modern paradies such as the Blues Brothers. On a more serious level, Monk was known to go through an entire tour without speaking a word to the other musicians, or to stand in the middle of his solo and dance instead of play!

John Coltrane

Coltrane was also born in North Carolina. He moved to Philadelphia in his teens. Coltrane's first instrument was the clarinet, but he switched to alto saxophone as he grew interested in jazz. In 1949, he had his first major professional break in joining Dizzie Gillespie's band. He remained with one of another Gillespie organization, switching to tenor sax until 1953. Coltrane recorded as early as the mid 1940s, but he received little recognition until the mid 1950s. His first truly significant recording came as second soloist to Miles Davis on the ground-breaking, "Cool" jazz composition "So What?" Coltrane's music evolved rapidly in the late 1950s, in part the result of his successful rehabilitation from heroin addiction and his association with Thelonius Monk, alto sax player Cannonball Adderly, and Miles Davis. Coltrane participated in some of Davis' most important recordings including Milestones and Kind of Blue.

Coltrane's musical sensibilites included the rapid runs of Bop played twice as fast (quadruple time). In the 1960s, he switched to the obsolete soprano saxophone, a move made perhaps as a result of his admiration of clarinetist Sidney Bechet and partially as a result of pain in his gums. New musical directions became evident in the 1960s, and Coltrane began to move toward a style of music in which harmonic structure grew less important. The style was known as "Free Jazz." The style was essentially the incorporation of Arnold Schoenberg's atonal classical composition methods, and involved melodic lines not encumbered by tradition concepts such as "key." The new directions are still often denigrated by "traditionalist" jazz musicians, but the impact in other musical styles is most evident in the work of Jimi Hendrix!

<< Home