African-American Currents in Rock ‘n’ Roll: Gospel, Doo Wop, and Other Styles in the 1950s and Early 1960s<

In historical accounts of rock ‘n’ roll evolution, Doo Wop is often largely ignored. In fact, Doo Wop emerged not only as its own style, but some of its basic features had considerable impact in other areas of popular music. Doo Wop was primarily an urban music centered in cities such as New York and Philadelphia rather than a southern phenomenon. Southern radios stations concentrated on “Rockabilly” and County-Western music. Nonetheless, total sales in the 1950s of Doo Wop records accounts for as high as 18 percent of the total!

Doo Wop emerged in stages. The origins of Doo Wop can ultimately be found in Gospel music, and the earliest seed of Gospel is, of course, the Spiritual of the nineteenth century. The Gospel style of singing dates back to the earliest tours of the choir of Fisk University in the late nineteenth century, tempered throughout its history by jubilant African-American Protestantism.

A significant offshoot of Gospel and an important intermediate stage was the commercial vocal singing group that emerged in the 1930s and 1940s. These groups and the music they sang are represented by the Mills Brothers and later by groups such as the Ink Spots. The music is not religious in text content like the Spiritual, but addresses the usual topic of the pop song, love, as well as humorous or pleasant everyday experiences.

Many of the basic tenets of the style may be found in these early commercial groups. First, the groups use instrumental accompaniment, but do not include the instrumentalists as formal components of the group. If there is instrumental accompaniment, it is kept to a minimum support function and, except for introductions, pushed far into the background. The parts normally carried by the instruments are carried instead by human voices. The typical commercial group and, by extrapolation the later Doo Wop group, consisted of a lead singer and several other back-up voices in various voice ranges. The groups invariably had someone who could sing bass, and another who could sing falsetto. Falsetto is the high-voice imitation of female singing by a male. Frankie Vallee of the Four Seasons is a prime example of a later white falsetto singer. The vocal-dominated texture was carried past commercial and Doo Wop music, serving as the model for later vocal groups such as the Shirelles and nearly the entire Motown entourage. Motown’s performer list included, of course, Diana Ross and the Supremes, the Four Tops, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, the Temptations, etc., all of which retained the musical textures established by the early commercial groups and Doo Wop.

The musical textures featured tight sung background harmonies that supported the lead or soloist. Sections of music sung by the group often alternated with sections sung by the lead singer. Other typical features included instrumental sections over which one member of the group would speak rather than sing a commentary on the song. In later pop songs that drew upon the style, the talking sections sometimes migrated to the beginning of the song. Here they served as an introduction that set the stage for the song to follow, as in “Runaround Sue,” an early 1960s hit by Dion and the Belmonts:

About a girl, I once knew.

She took my heart and ran around,

With every single guy in town.

The song that follows warns that Sue delights breaking hearts, sung from the point of view of someone who has been beaten at his own game. At work in this song is the double standard—it’s fine that men make sport, but it’s not fine when the tables are turned.

The chord progressions and principal melodies of the commercial and later Doo Wop songs were always kept simple, making them immediately understandable to the listener. The arrangements always contained a “show biz” or entertainment component, making the songs and performances first and foremost light entertainment. The groups were African-American, but the audiences were white. While the music of the early commercial groups possessed an easy, sing-song quality, the musical character of later offshoots underwent considerable changes with each successive generation. Doo Wop singers of the 1950s maintained a ballad character in some of their songs, but others started to display the forward drive and faster tempi of contemporary rock ‘n’ roll. Many of the songs built their musical tension by using triplet backgrounds (each beat is subdivided into a one-two-three count).

The triplet division also found its way into Rhythm and Blues and some later rock ‘n’ roll songs, and a particular chord progression became associated with Doo Wop. This chord progression was probably less often used than it is purported to be among the common folklore, but the progression is invariably given alongside twelve-bar Blues in beginning guitar lessons as one of the mainstay, “must know” chord patterns.

In the early 1960s, Doo Wop began to absorb rhythmic patterns from other styles. Reflecting the contemporary mambo trend in inner-city Hispanic music, the experiments in jazz by Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis, and the Hollywood television fascination with Florida as the hot place to be (Hawaii was the other paradise of the time), Doo Wop began to absorb rumba and tango. Most notable among the rumba influenced hits was the music of the Drifters. Some of the group’s hits were so well received that they are known today, directly or through “covers” (remakes by other artists), even among a younger generation not yet born! They include “There Goes My Baby,” “This Magic Moment,” “Save the Last Dance for Me,” “Some Kind of Wonderful,” “Up on the Roof,” “On Broadway,” and especially “Under the Boardwalk.” The resulting dance craze was the “calypso,” which was wholly misnamed since rumba and true calypso music have little to do with each other. Nonetheless, the calypso dances was an extremely effective weapon wielded in 1960s high-school dances by girls to prevent the boys from dancing with them! There are several features worth noting about “Under the Boardwalk.” First, the production values and carefully calculated arrangement are closely allied to the same kinds or values which characterize the Nashville Sound. Nashville producers discovered the relationship of “slick” and saleable in the music of Patsy Cline and others, and producers in other music styles learned the same lesson very quickly. In the 1950s and 1960s, the musicians recorded a track at the same time. Extensive editing of the recording was not possible, so the best take ended up as the release. The fact explains the simpler musical parts each musician played, but at least the recording reflected how the musicians actually sounded in live performances. The process stands in sharp contrast to today’s recordings. Editing may be performed to a fraction of a note, often a process now most often applied to make someone who has no talent into a star. Instead of actually performing live, lip-synching, dance routines, and light shows supplant artistry and ability.

Second, the background guitar work is more reflective of Mexican music than Cuban rumba! Lastly and not evident in listening, nearly all the Drifters’ hits were composed by the modern equivalent of Tin Pan Alley composers, the hired guns of popular music from the beginning of the twentieth century. The list includes, among others, the songwriting teams Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann and Gerry Geffin and Carole King. We meet up again with the latter in the music of the Shirelles. Carole King had a twenty-year career as a songwriter, like Willie Nelson in Country music, before she came into her own as a performer.

Doo wop-derived music underwent yet another change in the Motown era of the 1960s, the music unfolding with a moderate-tempo forward push furnished by a very prominent and heavy electric bass guitar line. The heavy bass line reaches back to Blues and in turn to African drum dancing of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries!

Doo Wop Chord Progression

Early Commercial Singing Groups:

Mills Brothers, “Tiger Rag”

Ink Spots, “Java Jive"

Doo Wop Rumba: Drifters (with Ben E. King), “Under the Boardwalk”

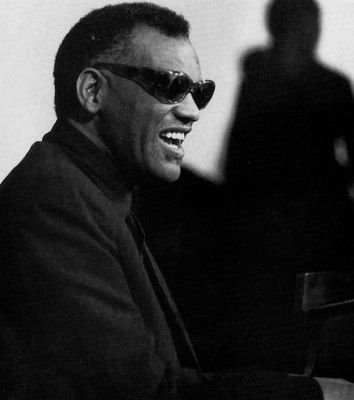

Ray Charles, Gospel, and Rock

Probably no other black musician of the era produced music that so well exemplifies the melding of many disparate musical and cultural styles as Ray Charles. Like his white counterparts in rock ‘n’ roll and country, notably Elvis Presley and Patsy Cline, the body of Charles’ work bears the marks of marks of many of the styles that preceded him but blends these older elements in new ways. Not insignificantly, the popularity of his music across racial lines bespoke an America that would soon be ready for the civil rights developments of the 1960s. Regardless of musical treatment, Charles’ songs are always within the bounds of good taste, a feature that added a dignity to the music without diminishing its musical, emotive, or lyrical punch. In this regard, Charles follows in the line of supper club singers but far exceeds their scope in universal content and sales.

Ray Charles

A very strong presence in Charles’ music is evidence of Gospel. The Gospel influence manifests itself in a certain angular and animated rhythmic feel and Charles’ almost universal use of background singers to compliment his singing. For the most part, Charles’ melded the Gospel practices to the ever-reliable Blues. His treatment of the music from song to song, however, differs significantly. Some of his songs, such as “Night Time,”come very close to earlier Blues, while others retain the “rift,” as well as some of the brass instrumentation, from the Swing orchestra.

Notably, many of his pieces incorporate not only Latin rhythms, but vestiges of Latin percussion treatment. The favored Latin rhythm is the rumba, and Charles was one of the first of the mainstream popular musicians to incorporate it. Yet other pieces reflect influences from a very unlikely contemporary style—Country! Two of his most important pieces, “Georgia On My Mind” and “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” feature the careful arrangements, string orchestra, and high production values that were concurrently cultivated in the Nashville Sound. Remarkably, both these songs were immense crossover hits, holding their own on the popular and Country charts!

Charles occupies an important place in popular music of the 1950s and early 1960s. His significance lies in the melding of disparate styles, without artistic compromise, into music not only desirable to a broad segment of the public, but embraced across racial and cultural lines. In short, Charles and his music stood as a bridge between very the different social realities of the America of the day.

“Night time” and “Busted” fall closest to the Blues category. “Night Time” is a twelve-bar Blues with accompaniment that sounds very close to the Chicago style. Principle, however, are found the use of the sax in place of the harmonica and the Gospel-style background vocals. The triplets in the background (the “one-two-three” count to each beat) link the song to both Blues and Doo Wop. The character of “Busted” is more rural, to a large part the function of the lyrics, despite the Swing Band orchestration and rifts in the background.

“Fool for You” blends style elements from Blues, Gospel, and Doo Wop. The Charles’ vocals stay very close to Blues, but his piano work and its bouncy, joyous dance through the current chord are more characteristic of church piano work. The background triplets are very heavily emphasized, a trait shared with Doo Wop that makes the overall progress of the rhythm seem labored yet fraught with energy.

The first part of the piano introduction to “Hallelujah I Love Her So” is straight Gospel piano, but it gives way in the second part to big-band Swing. The vocals are supported by “jazz-blues” and use “stop-time” to heighten the celebratory tone of the song. Even the “hook” line refers to the joy of Gospel in its borrowing of the word “Hallelujah,” a Gospel refrain standard. The chord progression is, as in all the other songs, Blues derived.

The rumba underpins “What’d I Say” and “Sticks and Stones,” though more obviously in the bass line of the former than in any particular feature of the latter. The use of rumba paralleled developments in modern jazz, particularly Dizzie Gillespie’s experimentation and promotion of it, and contemporary developments, largely confined to the Latino community in New York of Tito Puente and the mambo. Charles uses stop time as a prominent part of the stanza in “What’d I Say.” The electric piano and lack of horns gives the impression more of a piano-dominated rock band rather than a stripped-down Swing band or modern jazz combo. The overall effect of the accompaniment “Sticks and Stones” is of a 1950s jazz combo than of a Swing band. The use of the rumba in a commercial song intended for a “rock ‘n’ roll” audience, as was Presley’s “Hound Dog,” in bringing Latin rhythms to a mass audience.

“Georgia On My Mind” and “I Can’t Stop Loving Her” display all the same components of the contemporary Nashville Sound. Each song unfolds in very carefully prepared and controlled arrangements. The songs themselves are not Blues songs. “Georgia” was composed by Tin Pan Alley composer Hoagy Carmichael, the same musician who composed “Heart and Soul” on you CDs. “I Can’t Stop Loving You” was composed by Eddie Albert, an important country singer and composer of the period who also composed “You Don’t Know Me.” The use of bowed strings on both songs is reminiscent of those found on Patsy Cline’s ballad-torch songs. Charles’ piano work on both songs, played without using the left hand (bass) to furnish very tasteful and melodic “fills,” is also a feature one hears on Cline’s recordings and other country ballads. The background singers of Gospel are still present but, on “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” the number of singers has swelled to that of a small choir!

Finally, no playlist of the music of Ray Charles could be complete without “Hit the Road Jack.” The song is actually a set of variations over a prominent, descending repeated bass melody. The bass line was actually first developed extensively in the harpsichord music of the musicians at the Court of Louis XIV in the seventeenth century, but found new life in the rock ‘n’ roll of the 1950s and 1960s. It is found in songs such as Del Shannon’s “Runaway” and in Led Zepplin’s “Stairway to Heaven.” As different as it is melodically from the barrelhouse walk found beginning in 1930s Blues, the use of a repeated bass melody as the central component of the musical superstructure conceptually links this descending melody directly to the barrelhouse walk. Again, the “mice” (background singers) from Gospel play a prominent role, actually carrying the entire melody of the refrain!

New Directions in a Universal Style: Motown

Motown may also trace its roots to Gospel, but the forging forces were considerably different than a need for race-oriented musical voice. Berry Gordy, Motown’s founder, found that he could not sustain himself selling his beloved jazz records from the store he opened with his G.I. separation pay. Soon afterward, while working on the assembly line at the Ford Motor Company, he resolved to invent a new style of music that would sell and that would cross all lines of race, religion, or economic background.

Motown’s first home was a rented house in Detroit. There Gordy and others composed, rehearsed, and recorded their earliest music. Gordy’s corporate vision was one which reached from the top down. He maintained control of every aspect of the music, from its content and musical style to the clothes and deportment of his performers, on and offstage.

Gordy’s music usually followed certain formulas. The songs invariably contained “hook” refrains. Each song told a story about the truly universal topic, love, in order to make it appealing to both black and white audiences. Each stanza in a song told just a little more of the story, so that the listener had to listen to the entire song to learn what happens. The musical texture was both bass-heavy and layered, each layer consisting of a musical motive played on one of the instruments. The rhythmic layering was essentially a reinterpretation of the texture of African drum dance music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The guitar was pushed back into the rhythm section and, if there was an instrumental solo, it was played on the saxophone, a vestige of both Big Band Swing and Gordy’s beloved jazz.

Elements of blues were kept to a minimum. The twelve-bar blues progression was forsaken in favor of more sophisticated harmonic progressions derived from jazz but simplified by being filtered through pop music sensibilities. As in Doo Wop, his performers consisted of small vocal groups of three or four singers, of which one was the soloist. Gordy groomed his performers as musicians and as performers. There clothing was carefully chosen and simple dance choreographies that each group would follow onstage were developed. The performers were expected to adhere to high professional standards, and an arrest in private life invariably meant that the artist was dropped from the Motown line-up. Most of Gordy’s early groups are legendary today and include Diana Ross and the Supremes, the Temptations, the Four Tops, Smoky Robinson and the Miracles, Martha and the Vandellas, Mary Wells, Marvin Gaye, Jr. Walker and the All-Stars, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Stevie Wonder, and, yes, the Jackson Five.

Motown Traits Derived from Rock 'n' Roll

Rock 'n' Roll differs from Blues primarily in its energy, though other important traits include a more formal, contrived, self-conscious "white" delivery (even by Black musicians) and story lines that do not deal with love in the same way as Blues. Rock 'n' Roll is almost like "hyper" Blues, a trait clearly absorbed from the post war jump bands.

Motown shares this energy with Rock 'n' Roll, and might even have used Rock 'n' Roll as a model. In Rock 'n' Roll, the energy is found in the frenetic character of all the parts and at all levels of the music. In Motown, the vocal delivery is more relaxed, but the Rock 'n' Roll drive is retained in the rhythm section. The back beat is a pronounced feature, the most dominant characteristic after the vocals, and that back beat hunts down the listener tirelessly and relelentlessly. The bass line reverts back to the repeated note of early Blues in most cases, a characterisitic first modified from drum dancing. The bass drives the music, runs down the listener, and is found in nearly every early Motown song. "Heat Wave" by Martha and the Vandellas and the Supreme's somewhat later "You Keep Me Hangin' On" exemplify the device.

Suggested Listening

Martha and the Vandellas, "Heat Wave"

The Supremes, “You Keep Me Hanging On”

The Four Tops "(Sugar Pie Honey Bunch) I Can't Help Myself"

Diana Ross and the Supremes

If a melody is given in a Motown bassline, it is as an ostinato. An ostinato is a melody that is repeated (in the bass) throughout the song. The device emerged first as the "barrelhouse walks" of Blues. The barrelhouse walks were quickly picked up by Country musicians (i.e. the bass in Patsy Cline's "I Fall to Pieces") and early Rock 'n' Roll (i.e the bass in Elvis Presley's "Good Luck Charm").

More sophisticated ones emerged later in Rock in songs like Clapton's "Sunshine of Your Love" and Iron Butterfly's "In-A-Godda-Da-Vida." The latter title is the drunken singer's distortion of "in a garden of Eden." The ostinato is currently being used in a television commercial for a financial investment firm. If you are a younger student, embarass your parents by asking them if they own the record, then borrow it. In the case of Motown, the most famous ostinato of all time is found in "I Can't Help Myself." The ostinato is infectious and, again, as in most early Motown recordings, the beat is relentless.

Rhythm and Blues

Rhythm and Blues represents a black mainstream music that ran parallel, starting in the 1960s, to rock ’n’ roll and Motown, as well as other popular music styles. It also overlapped later styles, such as Funk, that evolved from it. Rhythm and Blues has, for the most part, remained separate from rock ‘n’ roll serving, as it will as music produced for blacks for blacks. It's connection to earlier black commercial singing groups, Doo Wop, and even Motown, especially in the use of chord progressions not based in Blues, is evident. The style was essentially an inner city one that could be compared in purpose to those found on earlier race records, that is, records produced by white record companies exclusively for black consumption. Rhythm and Blues evolved over time and, by the 1980s, began to feature musical style that had become, through the absorption of both jazz and commercial elements, one of great subtlety, sophistication, and talent, as it remains to this day.

Although the text covers R&B, a closer look at one of its most important icons, Otis Redding, is wothwhile. Redding is known today by most Americans for “Dock of the Bay,” his crossover hit, but his contributions to R&B and early Soul were extremely important. More so than many singers, Redding was able to convey a sense in his music that he really meant what he was singing regardless of the style, and this ability brings him into intimate contact with his listener.

Redding's music fit first and foremost into the category of modern race record, with some of his songs crossing to a general audience. Many white listeners who discovered him sought him out. In some respect, Redding's importance goes beyond the exciting but polished commercial products that Motown was producing on its assembly line. Redding's music stands as a message of human sensitivity at a time when white America was just coming to grips with its own racial hatred and fear.

<< Home