Early American Musical Theater: Minstrelsy

A great part of the disparity of characterization is ascribed to the region that spawned the minstrel show. Minstrelsy was not a southern invention, but a northern one! Although the little skits that led to the minstrel show existed for at least two decades, the first formal minstrel show was mounted in Boston in 1844. Northern cities, including New York, became the home of this new type of entertainment.

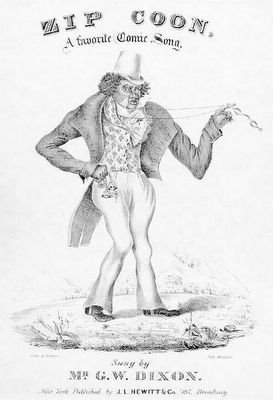

Two Racial Stereotypes: Jim Crow and Zip Coon

Two particularly vicious racial stereotypes emerged as principal characters in Minstrelsy, "Jim Crow" and "Zip Coon." The earlier Jim Crow character emerged in the 1820s, the product of a stage persona/negro impersonation developed by Thomas Dartmouth ("Daddy") Rice. Jim Crow was protrayed as an embittered and raggedy servant who believes, perhaps correctly, that he is more intelligent and knows more than his master. Jim Crow was often portrayed as suffering an infirmity in one of his legs, and his grotesque dance added to the amusement of the audience. The character is believed to be based upon a real servant that Rice observed. Segregation laws enacted in the first decade of the twentieth century, the "Jim Crow" laws, derive their name from the Minstrel character.

Jim Crow

The persona of "Zip Coon" was developed by George Washington Dixon, an outgrowth of his circus act modified for the New York City burlesque stage. The character, whom he introduced around 1929, became his greatest theatrical success. Dixon portrayed Zip Coon as a dandy and a blowhard who both portrayed himself as a "educated scholar" and incessantly bragged about his sexual conquests. Zip Coon was also known to frequently bother with his advances one of the female kitchen help named Dinah. Dixon's black-face impersonation was acccompanied by singing and dancing, and the melody of the "theme song" Dixon associated with the character comes to us today as "Turkey in the Straw." The lyrics follow:

O ole Zip Coon he is a larned skoler,

Sings posum up a gum tree an coony in a holler.

Posum up a gum tree, coony on a stump,

Den over dubbler trubble, Zip coon will jump.

Zip Coon

Stephen Foster: the Commerical Aspects of the Parlor and Minstrel Song

Stephen Foster (1826-1864) is credited with fusing the disparate elements of American music into the first coherent national song style. Foster was also, however, one of the first to have helped to forge Minstrel and parlor music into a specific style and to capitalize on them.

Foster was born into a middle class family in Pittsburgh in 1826. As a child, he showed a keen interest in music and throughout his early years was tutored in the subject. His most imfluential teacher was a prominent and versatile local musician, a German immigrant named Henry Kleber. As an adolescent, Foster enjoyed the friendship of children from prominent Pittsburgh families, many of who gathered in his home to sing. One of his best-known songs, "Oh, Susanna," might have been composed for these meetings.

Foster's first song was published when he was only 18. His earliest professional endeavors, however, were not in the field of music, but as a book-keeper in his brother's steamship firm in Cincinnati, Ohio. During this time, Foster continued to publish with a local firm. Among the pieces he published was "Oh, Susannah," and the song proved not only to be his first big hit, but also the event that convinced him to turn professional.

In 1850, the young Foster, already with 12 published songs to his credit, returned to Pittsburgh. Between 1850 and 1860, he moved back and forth between Pittsburgh and New York, where his publisher was located. After 1860, he moved permanently to New York. His honeymoon trup of 1852, a month-long steamship ride up the Mississippi River was the only time Foster ever spent in the Deep South.

Foster's work method included the study of all the popular styles of music of his time, including the music brought to America by the burgeoning immigrant population. He crafted the melodies and lyrics of his songs to be immediately understood by every member of the working class. His early musical training and study of the music of immigrants was the likely source of the formality of his songs, a formality that typified the European piano art song by composers such as Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann.

Foster's early minstrel songs, which were called "Ethiopian" songs, contained racial stereotyping as well as "dialectic" language (see Zip Coon" above for an exampel). As he grew more ambivalent toward slavery, the character of his lyrics evolved in character. They did not view the Old South in a wholly sentimental light. Instead, his characters lived in the present, had identities and personalities and emotions, and interacted with each other.

"Nelly was a Lady" (1849) was likely the first song composed for a white audience by a white composer that depicted a slave couple as a loving and dedicated husband and wife. The title "lady" was one that, in its day, was reserved only for well-born white women. In time, Foster replaced the term "Ethopian" with "plantation" in referring to his songs, and ultimately replaced "planatation" with "American."

Foster even informed Christy, the leader of the tmilieu's most important minstrel troupe, that some of his songs should not be performed in a comedic spirit, but in a "pathetic," compassionate one. Likely inspired by contact with important abolitionists such as Frederick Douglas, Foster helped to publish an anti-slavery newspaper and even produced a volume of anti-slavery verse.

From the 1850s until his death, the topics of Foster's songs focused less on race issues and more on universl themes such as the longing for home and the times spent there. "Old Folks at Home" was composed during this period. Foster also understood the realities of the marketplace, and devoted significant energy to the composition of parlor music, songs intended for amateur rendering in the home.

Foster's earnings came only from the 5-10% royalties on sheet music sales. Copyright laws did not provide income from other composers' settings of his songs, pirate broadsheet printings, or performances. Despite limited avenues, Foster's yearly income would be worth, in today's terms, millions of dollars. In his later years, much of this income was devoted to a life of dissolution. He died in a Bowery hotel in 1864, at age thirty-seven, after gouging his throat in a bathroom fall. At the time of his death, Foster had about forty cents in his pocket.

Stephen Foster

Ugly Performance Realities of Minstrelsy: Blackface

It was not enough to humiliate the black man with songs, language, and dancing that demeaned nearly every aspect of his existence. The Minstrel show also found cheap laughs in attacking the very physical appearance of the African American in the practice of blackface, the application of burnt cork to the faces of white performers. White audiences grew so accustomed to blackface that later when black minstrels, called delineators, took to the stage, they too had to wear blackface in order to be well received! The delineator was purported to give a more true rendering of life and song on the plantation but, in reality, audience tastes forced them to adhere to the racial stereotyping already established in the genre.

Blackface Minstrelsy

Blackface was parlayed in the twentieth century into a larger than life phenomenon, with the invaluable assistance of the new recording and movie industry, by Al Jolson (1889-1950). Born of Jewish Lithuanian parents, Jolson had, by 1911, already developed with immense success on Broadway the key elements of his performance style. These included blackface, direct address of the audience and a remarkable rapport, exhuberant gestures, operatic-style singing, whistling, and his signature expression "you ain't seen nothing yet!"

The achievements of Jolson's career are staggering. He starred in The Jazz Singer, one of the first highly successful "talking" flims. Like Neil Diamond's version of the film, The Jazz Singer featured very little, if any, jazz. Jolson's singing and performance style were rooted in vaudeville at the turn of the century, not jazz. The song he introduced in The Jazz Singer, "Mamee," later became a racial slur.

Jolson's recording career included sales that topped the million mark, and it is estimated that the total sales of his records to 1950 trails only those of Bing Crosby, Paul Whiteman, and Guy Lombardo. Among the songs he popularized include "You Made Me Love You," George Gershwin's "Swanee," "April Showers," "When the Red, Red Robin Comes Bob, Bob, Bobbin' Along," and "Avalon." After his retirement from the stage, Jolson found a career in radio.

As late as 1948, well after his retirement from the stage and despite competition from Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, and Perry Como, the various popularity polls still voted him as the "Greatest Entertainer Ever." Later important entertainers such as Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, Elvis Presley, Mick Jagger, Rod Stewart, and Jackie Wilson have publically referred to Jolson as such, and have acknowledged a debt to him in the formulation of their stage acts. Jolson is often ignored today because his use of blackface is considered racially insensitive, but it should be noted in his defence that his usage was no different than other white and black performers of his time.

Al Jolson

<< Home