Chicago Blues: An Urban Voice with Rural Origins

Elements of Style and Instrumentation

In cities such as Chicago, blues ensembles began to form that often consisted of string instruments. This shift at once represented the evolution of the rural Blues and a break from the traditions of the brass ensemble found in cities of the deep South such as New Orleans. These ensembles featured a new invention, the electric guitar, and the music they generated was intended as a club entertainment to which one could dance. The harmonica also grew in importance as a solo instrument. The piano was also sometimes included, though it essentially replicated the role of the electric guitar as both solo and rhythm instrument. Urban Blues was the critical intermediate stage to "rock 'n' roll."

Text subjects, often improvised, were also more sophisticated and reflected the difficulties of urban rather than rural life. The texts more often feature woes induced by alcohol, infidelity, jealousy, and the lack of material goods that whites more easily acquired. Even cars received mention, the Cadillac and Lincoln automobiles, the badges of success and status in the day, were the favored for inclusion. Humor often disguised real pain. A memorable line from a Muddy Water's tune describes infidelity and betrayal: "Luther, there's another mule kickin' in your stall."

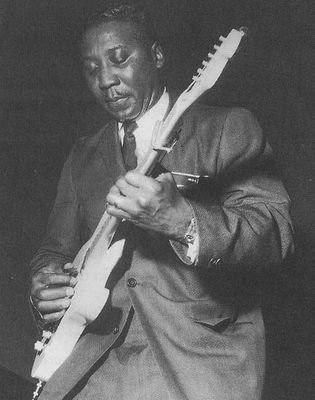

The pioneer of urban Blues was, of course, McKinley Morganfield (1915-1983), aka Muddy Waters. Waters grew up in Clarksdale, Mississippi, a part of the Delta, and was a singer and guitarist. Like so many before him, he found his way upriver to Chicago, where he adapted the rural Blues of his youth to the new environment of the rough, black working-class bars of this industrialized northern city. His importance is inestimable: nearly every subsequent important urban blues singer, guitarist, or piano player was at one time or another an alumnus of his band, including Buddy Guy. An exception is B.B.King, who is part of the same tradition and likely the only living representative of the early school.

McKinley Morganfield, aka Muddy Waters

An arrangement for two guitars of Muddy Waters' "Standin' Around Cryin'" is given in the audios. It is transcribed note-for-note from the original song. To demonstrate the strong similarities of urban and rural blues, a version of Robert Johnson's rural blues song "Love in Vain" is also given among the audio files. Unlike the original, it is given the treatment of the urban blues. Here song is given in a distillation of how Johnson sang it. The bass, singer's melody, and guitar answers remain intact. A second guitar part, however, is improvised over the original song in emulation of the early Chicago style to show the methods by which Muddy Waters "modernized" the rural blues of the solo singer/player to become electrified music for the small electric string band.

<< Home