American Music Takes Shape: the Musical Melding of Two Cultures

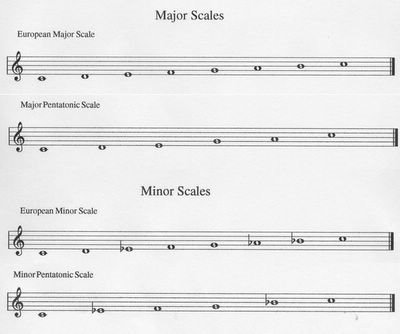

Since the late sixteenth century, European music has been characterized by melodies that are composed using either the major or the minor scale supported by chords derived from those scales. Curiously, many of the folksong and fiddle tune/dance tunes of the British Isles, especially Scottish music, uses a variant in which the fourth and seventh notes of the major scale are omitted. African musicians, especially fiddle players, were first exposed in the colonial days to this scale. The adaptation of existing melodies to make new ones is not unlikely. Today the scale is called the “major” pentatonic. African Americans absorbed it into their music, almost as the preferred scale, from their master’s culture. The majority of Spirituals utilize the major pentatontic scale. The spiritual "You Can't Cross Here" exemplifies the sound of the major pentatonic scale.

A partial explanation for the heavy emphasis in slave music upon the major and major pentatonic scales is found in the rules established by the slave owner; up tempo, major-key songs kept the work moving and the slaves’ spirits high. African American songs that utilized the minor scale were rare before the late nineteenth century. Because minor-key music was suppressed, music such as the “sorrow song” spiritual could not emerge until mid-century or later, when former slaves were free to sing what they pleased. “Gang” work songs, one of the musical staples of slave life virtually disappeared with the end of the plantation system. As noted, this type of work song lived on in the penal and military systems.

Minor keys, discouraged by work overseers, found use in "sorrow songs" that emerged at mid-century. The sorrow song may be regarded as the prototype for blues. The scale used by African American singers was a variant of the European minor called the "minor pentatonic." Like the major pentatonic, it was a gapped scale that omitted the second and sixth notes of the scale. The minor pentatonic scale is the most prominent scale in early rock ‘n’ roll and in white blues of the 1960s. The minor pentatonic scale is exemplified in the video "Motherless Child".

Comparision of European to Penatatonic Scales (as used in Amercian music)

It was not unusual for African American musicians to combine the major and minor pentatonic scales. Often, a spiritual might be sung nearly all the way through using the major pentatonic. In the closing measures, however, the sing might opt to borrow the third from the minor pentatonic, effectively creating what would later be called in in blues and jazz, a "blue note."

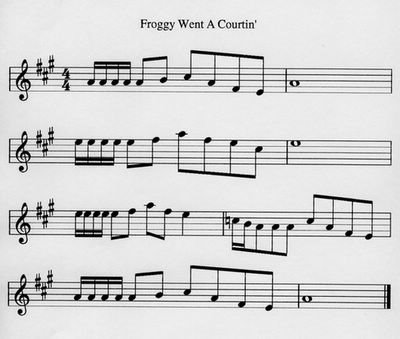

In the nineteenth-century, Spiritual-influenced folksong "Froggy Went a Courtin,'" the melody uses the major pentatonic scale until the sixth measure. Here the third note of the scale, C#, is lowered to become the C natural note of the minor pentatonic scale. Here the musician actually sings or plays the third from minor in a song in a major key. The shifts between the major and minor pentatonic scales became the backbone of blues and supplied the notes, primary among them the minor third, that we today call "blue notes."

"Froggy Went A Courtin'"

Harmony

Harmony, or the interrelated quality of the notes of a scale as they are sounded simultaneously with other notes from the same scale, is one of the crowning achievements of Western culture. African musicians encountered it when they were brought to the mainland from the islands of the Caribbean in white songs, hymns, and dance music. The earliest slave usage would seem to be in the music of the “strum-strum,” or banjo. Since very little African American music was recorded earlier than the second half of the nineteenth century, the nature and sophistication of chords used in dance music, if chords were used at all, is unknown. Usage of harmony in a way more consistent with European tradition, that is, in the regular repetition of a pattern of chords as a background or superstructure for a melody, is implicit if not explicit in the melodies of the Spiritual.

The chords most frequently used are those built upon the first, fourth, and fifth notes of the scale, also called the primary chords. They are named after the number in the scale of the pitch, or I, IV, and V. They are still the most common chords in popular music, ranging from the spiritual and the blues to country, folk, rock, metal, etc. Two styles that stand as exceptions are jazz, in which the chord progressions are often as advanced as those of European classical music, and rap, which often does not use chords at all.

Rhythm

No sharper is the contrast of musical styles between European and African music than in rhythm. European music evolved over the centuries to place harmony, a strict system that governs the simultaneous sounding of three notes, the chord, over rhythmic subtlety. As noted, harmony is the greatest music triumph of Western culture, and other cultures that use harmony absorbed it from the West in recent times.

The use of a repeated pattern of chords as a musical superstructure is the single greatest obstacle to sophisticated rhythms. The important notes must be sung at the same time as the arrival of the chord that contains that note. The movement of the chords, then, must be regular and predictable. If you listen to any composition in the classical repertory, you will be immediately struck by the sophistication of the melody and harmony, especially in the ability of the composer to build an extended composition that is derived from a short, basic melodic idea. Listening with new ears, however, you will notice that the rhythmic components, even in the music of Europe’s most significant composers such as Beethoven, are really quite simple.

Systemized harmony did not play a significant part in African music. Melodic lines were sung monophonically. Monophony indicates a single melody (the number of singers does not matter if all sing the same tune) without harmony or second melodies. The supporting drumming patterns do not have to be linked directly to the melody except in that the melody and basic time of the drums must follow the same basic beat. As a consequence, sophisticated rhythms were used to compensate for the lack of harmony in African music. Remember that descriptions of the dancing in places like Place Congo did not need anything but a drum beat to occur!

The sophistication of African rhythms often overwhelms the Western ear. Often they do not make sense at first hearing but reward anyone who is willing to sit and listen really carefully. The apparent cacophony of African drumming is often the result of polyrhythm—two or more independent rhythms beat simultaneously! Here only the basic beat is shared, the rhythms are otherwise independent of each other. Each will share the same first accented beat when the music begins, and then the patterns will get out of synchronization with each other. At some point, however, the various rhythms will cycle through and all the patterns will come together on that first accented beat!

Another point of confusion is another African feature, additive rhythm. Here the basic number of the beat unit does not remain constant, as in European music. Hence the count or measure might feature three beats at the onset. At some point, the count or measure shifts to four beats, then five, and so on. At some point it reverts to the basic unit.

The effect, at least in the experiments in European music by early twentieth-century composers such as Igor Stravinsky, is one “chugging.” Stravinsky’s Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) features additive rhythm, and these rhythms actually caused a riot at the debut in Paris! In his years with the Ballet Russe in Paris, Stravinsky was exposed by Pablo Picasso and various exhibitions and concerts to African art and music. His interest is manifest in the polyrhythms and additive rhythms that he often employed in his ballet compositions.

The predominant character of American music in part rests upon the melding of European harmony and African polyrhythm. Slaves were exposed to harmony from their first days in the New World in hymns, white folksongs (mostly English ballads) and even white dance music. Harmony required that chords supporting the melody occurred at regular intervals of time, usually every four beats. European composers were historically content to fashion melodies in which the important notes occurred at the time of the chord change.

African American musicians found great value in harmony, but also wished to retain the polyrhythmic character of their music. Their solution was syncopation. In the narrowest sense, syncopation is defined as an accent where not accent is expected. You can demonstrate the principle by counting or beating out loud 1-2-3-4 for several cycles. First stress “1” by making it louder. Then count again, but stress “2” in one of the cycles.

The African American musician was able to create a sense of polyrhythm, essentially a “quasi-” polyrhythm, in his adoption and adaptation of Western harmonic concepts. Like European music, the chords changed regularly and predictably on the first beat of a predetermined cycle in the count. The melody, however, did not begin, end, or feature important melodic notes on the first beat of the count. Instead, he avoided the first beat, essentially putting the melody out of phase with the unfolding of the chords. The effect is a normal and accepted feature of American music and a feature that sets American music in the fore with regard to the music European music of the twentieth century. American cutting-edge music was a popular music that was so good that it could stand favorably with some of the best European classical music of the time.

The syncopation of African music, as it has been absorbed into American music, is the feature that gives our music its rhythmic forward drive, its “up” character, and its swing. It pervades nearly all styles of our music, from the geriatric tunes of the elevator-music orchestra to the most raw from the street. We’ve all grown up accustomed to hearing these syncopations. Curiously, most Americans become aware of the complexity of syncopation when they take music lessons and see it for the first time written on the page!

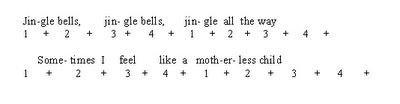

A student-participation comparison follows. “Jingle Bells” demonstrates European rhythmic sensibilities. The "sorrow song" spiritual “Motherless Child” demonstrates the African American compromise of chords and polyrhythm (see below for full text and music). In the latter, the melody “straddles the bar,” that is, begins and ends in mid-count. Tap your foot down on each number. This "down tap" is called the "downbeat." The symbol “+” represents the "upbeat," or the highest position of the toes when one lifts his foot to tap. In each example the appropriate chord is stummed on each "1."

Comparison of melodic rhythmic distribution in "European" and African-American music (it was a standard practice to sell apart families, hence the source of the title "Motherless Child")

Song Stanza and Text Forms

The formal influence of strophic art song (songs that have repeated musical stanzas and high brow texts) and the Protestant hymn upon the British ballad is apparent. Dance music, with its clear sections of music, was also influential. Both aspects found their way into white American folk songs in the four–line stanza that remains in use today. Another salient poetic feature is the presence of rhymed line ends:

Yankee Doodle went to town a’ riding on a pony,

Stuck a feather in his hat and called it ‘macaroni.’

The form of slave songs, by necessity, evolved quite differently. Responsorial singing, especially in work gangs, gave rise to forms in which the first part of the line, the “call” was sung by the soloist and the “answer” was sung by the gang. The call presented the new information that moved the song along. Often the texts were improvised by the leaders, and didn’t make a great deal of sense. The answer contained the same text, usually an affirmation. An excerpt from an 1841 Virginia “corn” song illustrates the form:

Call: I loves old Virginny

Answer: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: I love to shuck corn

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: Now’s pickin’ cotton time

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: We’ll make the money boys

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: My master is a gentleman

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: He came from the old Dominion

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: And mistress is a lady!

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: Right from the land of Washington

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: We all live in Mississippi

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: The land for making cotton

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: They used to tell of cotton seed

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: As dinner for the negro man

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: But boys and gals it’s all a lie

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: We live in a fat land

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: Hogmeat and hominy

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: Good bread and Indian dumplin’s

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: Music roots and rich molasses

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: An old ox broke his neck

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: He belong to old Joe R---

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: He cut him up for negro meat

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: My master say he be a rascal

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: His negroes shall not shuck is corn

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: No negro will pick his cotton

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: Old Joe hire Indian

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: I gwine home to Africa

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: My overseer says so

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: He scold only bad negroes

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

C: Here goes the corn, boys

A: So ho! Boys! So ho!

Once the original leader has run out of ideas, a new leader steps in without missing a beat! The soloist was free to improvise the melody of the call as well as the words, but the answer was sung to the same words and music. The answer, then, may be regarded as a refrain.

The impact of the Spiritual, which was modeled after the Protestant hymn, upon form is evident in stanza structures that began to emerge in the nineteenth century. Each line of the first three lines is sung to a similar melody; the last line of the stanza, the one containing the important information or the “punch line,” is sung to a different melody. Variants also may be found in which two lines are repeated and the third line is the punch line. The melodic structure is still call and answer, but both parts of the line are sung by a single singer. Note that the text changes in the three line portion. The form is a crucial one in the early blues.

The aforementioned sorrow song spiritual “Motherless Child” follows, and two stanzas of the music are given in the video. It dates from the nineteenth century and clearly, on the basis of the content of the text, was a heart-wrenching product of slave life. Again, it must be stressed that the sorrow song is a minor key Spiritual and, as such, is the likely prototype for blues!

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

Den I git down on my knees and pray.

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

I wonder where my mother’s gone.

Sometimes I feel I’d never been borned,

Sometimes I feel I’d never been borned,

Sometimes I feel I’d never been borned,

Den I git down on my knees and pray.

Wonder where my baby’s done gone,

Wonder where my baby’s done gone,

Wonder where my baby’s done gone,

Git down on my knees and pray.

Sometimes I feel like I’m a long way from home,

Sometimes I feel like I’m a long way from home,

Sometimes I feel like I’m a long way from home,

I wonder where my sister’s done gone.

Sometimes I feel like I’m a long way from home,

Sometimes I feel like I’m a long way from home,

Sometimes I feel like I’m a long way from home,

I wonder where my brother’s done gone.

Sometimes I feel like I’m a long way from home,

Sometimes I feel like I’m a long way from home,

Sometimes I feel like I’m a long way from home,

I wonder where de preacher’s done gone.

Etc.

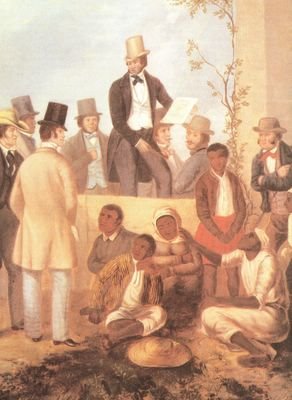

Slave auction

Some spirituals modfied the form to feature two lines of the same text followed by a punch line. This form ultimately served as the basis of the twelve-bar blues discussed in a subsequent section.

By mid-century, Spirituals began to utilize hybridized forms. The four line stanza was retained but now it was turned into a refrain to be sung by the group in the same manner as the “answer” refrain of the earlier corn song. The first two or three lines are sung to the same melody, the last line (punch line) uses a different melody. The “call” portion still gives the content, but now the song might actually start with the refrain. The “call” portion also shows the evidence of the same Protestant hymn influences that lead to the formulation of the four-line stanza of “Motherless Child.” It is obviously a three-line variant of the four-line stanza form. The first two lines are sung to one melody; the third line (punch line) is sung to a different one. The melodies of the “answer” refrain and the “call” stanza are not the same except for the final shared line. The line features the same text sung to the same melody and offered the opportunity for responsorial singing in the “call” stanza. More accurately, it should be called “stanza-refrain” since a verse is a single line. This form is actually a forerunner of the “verse-chorus” form of early rock and role and contemporary popular music. It is today especially prevalent in country songs. (Note that the author of your text got this form wrong, citing it as a rock 'n' roll innovation rather than the continuation of an older practice of singing Spirituals. Getting caught out, in a printed, very public forum, is a research scholar's worst nightmare!). The text of “Sinner, You Better Get Ready” follows. Note the attempts at rhyme in some of the "call stanzas."

“Answer” refrain:

Sinner, you better get ready,

Sinner, you better get ready,

Sinner, you better get ready,

For the hour is comin’ that a sinner must die!

“Call” stanza:

I looked at my hands, my hands was new

I looked at my feet, my feet was, too!

The hour is comin’ that a sinner must die.

“Answer” refrain:

Sinner, you better get ready,

Sinner, you better get ready,

Sinner, you better get ready,

For the hour is comin’ that a sinner must die!

“Call” stanza:

My name’s written in de book of life,

If you look in de book youll find it there,

For the hour is comin’ that a sinner must die!

“Answer” refrain:

Sinner, you better get ready,

Sinner, you better get ready,

Sinner, you better get ready,

For the hour is comin’ that a sinner must die!

“Call” stanza:

De good old chariot passing by,

She jarred the earth and shook the sky,

For the hour is comin’ that a sinner must die!

“Answer” refrain:

Sinner, you better get ready,

Sinner, you better get ready,

Sinner, you better get ready,

For the hour is comin’ that a sinner must die!

<< Home