Country Music in the Twentieth Century

Folk and Country music share the same wellspring. Both began as the music of rural whites and both retain the elements of American music established in the conflation in the nineteenth century of the Anglican hymn; African American Spiritual; English ballad and fiddle tune; banjo music; and Minstrel-parlor song. Both folk and country styles feature simple chords, simple melodies, simple stanza forms, and topics that relate to the life of the ordinary man. The evolution of each style, however, in the twentieth century is quite different, and the direction of each can be traced to contemporary social situations and radio and recording technology.

The Wellsprings of Modern Country Style in the 1920s and 1930s: Vernon Dalhart, Jimmie Rodgers, and the Carter Family

Surprise Commercial Possibilites in the 1920s and a Style of Singing: Vernon Dalhart

Vernon Dalhart was born in Jefferson, Texas, in 1883. His real name was Marion Try Slaughter, but the principal name under which he recorded came from Vernon and Dalhart, two towns where he worked as a cow hand in his teenage years. Dalhart was raised on a ranch a few miles outside the river town of Jefferson, the seat of Marion county. Dalhart was a musical child, learning to sing and to play the harmonica, the jew’s harp, and the kazoo. In later life, he often included these instruments on his recordings. His singing was encouraged. Dalhart likely began singing professionally at an early age. The Kahn Saloon in Jefferson was a likely early venue, but was also the site of his father’s death when Dalhart was ten. The death resulted from an argument between his father and maternal uncle.

In Dallas, the young Slaughter was encouraged to develop his voice, and he began studying music at the Dallas Conservatory of Music while working at various jobs to support himself and his growing family. He had married Sadie Lee Moore-Livingston in 1902 and by 1904 had a son, Marion Try, III, and a daughter, Janice. Sometime before 1910 he moved his family to New York to further his musical education. He supported his family by working in a piano warehouse and taking occasional singing jobs, mostly as a church soloist, while studying voice to prepare himself for opera and the concert stage, his eventual goal.

Dalhart had limited success on the stage. In 1912 he played a minor role in Puccini’s Girl of the Golden West. In 1914, he played the lead tenor role in Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore, and toured with various companies. In 1916 he auditioned for the Edison record company to record. In a second audition he sang directly unto the wax role for Thomas Edison, who liked Dalhart’s singing because every word was clearly pronounced.

Dalhart’s releases on the Edison label, as well as other titles on other record company labels under other names, had limited success. One favorite alias was Bob White. One aspect of his employment for Edison involved demonstration/recitals in which the audience was asked if it could tell the difference between the live and recorded performances. During this period he discovered, however, his predilection for “dialect” songs, songs that required regional accents and colloquialisms. Chief among them was the Southern black accent, an accent he claimed was just his natural Texas speech.

In 1918, Dalhart had left Edison (his contract expired in 1919) and began recording as a freelancer for the Victor Talking Machine Company. The early dozen recordings were only moderately successful. The Victor publicity of the early 1920s called Dalhart “one of the best light opera tenors in America…there is no burlesquing in Mr. Dalhart’s singing of negro songs. To quote his own words, he simply imagines he’s ‘back home’ again and he sings as the spirit and his home experiences dictate.” The million-seller success in 1924 of “The Wreck of the Old 97” and the record’s B side, “The Prisoner’s Song,” (on CD), on the Edison label, assured his place as a star but also defined the direction of the rest of his career. For nearly the next nine years, Dalhart recorded several hundred songs, nearly all of which were “hillbilly” songs. He recorded this body for several labels, and to avoid contractual obligations, he used pseudonyms including Al Craver, Tobe Little, and Jeff Fuller. The materials from one label to the next were often the same. With releases on subsidiary labels, his issues ran into the thousands and he virtually dominated, though under an extensive variety of names, the hillbilly market.

A typical Dalhart recording featured, in addition to the singing, a violinist, often Adelyne Hood or Murray Kellner, and a guitar accompaniment, most likely played by Carson Robison, his recording from 1924-28. These accompanists sometimes sang harmony, in turn, and Robison also composed many of the songs and whistled. Occasionally Dalhart would play his harmonica or jew’s harp. [L. Raderman plays the viola on “The Prisoner’s Song”]. The mainstay Dalhart repertory included minstrel-stage songs and cowboy songs he learned as a child in Texas, but his most successful songs were topical ones inspired by current events. He was an extremely versatile musician, however, and felt at home singing repertory as diverse as to include light opera, popular songs, hymns, comedy songs, and children's songs. He also often sang and recorded in duets, trios, and quartets. He even occasionally sang for dance bands. His recording output was stupefying in its magnitude—over 3800 sides in the United States and another 1160 overseas.

Like many other musicians, Dalhart’s music career ended with the Depression. He made a considerable amount of money after the success of “The Prisoner’s Song,” but he had also invested a good deal of his earnings in the stock market shortly before the Crash of 1929. Attempts to revive his career in the 1930s failed. By 1938, he was forced to sell his large estate in upstate New York and move into more modest quarter. He moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1940, where he advertised himself as a voice coach. During World War II, he served as a guard at a local defense plant. After the war, he worked as the night clerk at a Bridgeport hotel until his death in 1948. The style of music to which he had contributed so much had evolved past him.

Many scholars do not regard Dalhart as contributing significantly to the stylistic development of country music. Yet they overlook the facts that the commercial success of Dalhart’s recordings and their wide circulation disseminated a body of songs embraced and absorbed into the repertories of both amateur and professional country musicians. His singing style brought the flavor of country (and Southern) music to an audience not receptive to hillbilly music, hence broadening the consumer base for the genre and popularizing it among new audiences. The legendary record producer who had discovered and made the careers of both Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, Ralph Peer, said of Dalhart in Variety in 1955 “Dalhart had the peculiar ability to adapt hillbilly music to suit the taste of the non-hillbilly population . . . he was a professional substitute for a real hillbilly.” Because Dalhart drew upon in part upon American folksong sources for materials, he may be regarded as the prototype of the later folksong collector and singer. The category must include the Carter Family, Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, the Kingston Trio, and Joan Baez, among many, many others. Dalhart’s singing style also established a model of the straightforward, unadorned delivery of the melody. The style stands in sharp contrast to the heavy melodic ornamentation of Jimmie Rodgers, Billie Holiday, and others Blues-influenced singers, but its role as a model can be seen in the singing of the Carter Family, Bob Will’s vocalists, Patsy Cline, and many singers to the present. Finally, it should be noted that Dalhart made the shift from "ole-timey" hillbilly instruments before both Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family. The guitar replaced the banjo, and the violin, an American hillbilly mainstay, is played in a more classical style, not in the style of mountain fiddle.

Vernon Dalhart

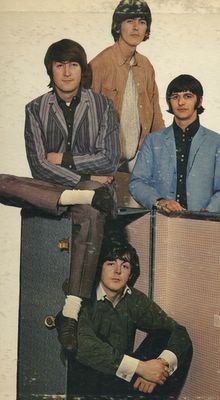

The “Father of Country Music,” Jimmie Rodgers

Rodgers was born on September 8, 1897 in Meridian, Mississippi. During his early years is lived alternately with relatives in southeast Mississippi and southwest Alabama. His father was a maintenance foreman on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. His love of show business and wanderlust began early, and by the time he was thirteen he had organized and begun traveling shows. In each case he was retrieved by his father and, soon thereafter, his father got him a job on the railroad as water boy for his father’s work gang.

A few years later and with the help of his conductor-older brother, he became a brakeman on the New Orleans and Northeast Railroad.

In 1924, Rodgers contracted tuberculosis. The disease temporarily ended his railroad career but afforded him to return to his music. He organized a successful traveling show, but its run was cut short by the devastation meted upon its assets by a cyclone! He was forced to seek more regular employment and despite poor health, took another brakeman job on a Florida railroad based in Miami. As his disease worsened, he relocated to Tucson, Arizona, in hopes that the desert air would give him some relief. There he worked, again on a railroad, in the less arduous position as a switchman. When the job ended in less than a year, he relocated, with his wife and daughter, first to Meridian and then, in 1927, to Asheville, North Carolina. Asheville had no railroad, but it had a newly-flourishing music industry.

Rodgers first performances, backed by a band from Tennessee that he had recruited, were broadcast on Asheville’s radio station WWNC. His band mates proved to be instrumental in securing the first big break by arranging to audition for Ralph Peer, who had come recruiting to Bristol. During the recording audition an argument arose over how the group would be billed. In response, Rodgers offered to sing one of the takes by himself. Suddenly Rodgers found himself on his professional way alone!

Rodgers auditioned in August 3, 1927. Peer’s response was immediate, and Rodgers cut his first solo test tracks for the Victor Talking Machine Company the next day. The tracks were released in October of the same year and were a moderate success. By November, he convinced Peer to record him again. He traveled to New York and recorded in the Victor studios in Camden, New Jersey. Camden session resulted in four tracks, among them “Blue Yodel,” originally titled “T for Texas.” Another cut. “Away Out on the Mountain” sold half a million copies. “Away Out on the Mountain” made Rodgers a star, billed as “Jimmie Rodgers, the Singing Brakeman.” “Blue Yodel #9,” originally titled “Standin’ on the Corner,” was recorded in 1930 and featured a struggling young jazz trumpeter and his piano-player wife, Louis Armstrong and Lil Hardin. Tours, including ones with the great humorist Will Rogers, followed, and the houses to which he played were nearly always sold out.

By 1932, Rodgers’ tuberculosis had significantly worsened. He had given up touring but still played a weekly radio show in San Antonio, Texas. His last recording sessions began in New York on May 17, 1933, where he had agreed to record twelve new songs. Rodgers was so sick that he was unable to record more than three or four songs at a time. Three sessions stretched into a week. Rodgers collapsed on the street on May 26. He died a few hours later in his hotel room of a massive hemorrhage.

Jimmie Rodgers in street clothes

Jimmie Rodgers’ music was a mixture of elements from many different styles of American music. The influences include older traditional and folk melodies of his southern home, German yodeling (refined in his treatment to become a standard feature of country music), the work songs of railroad work gangs, and even jazz. Central to his style, however, is rural Blues.

Rodgers’ importance and impact upon subsequent generations of country musicians is beautifully summarized by Nolan Porterfield’s adaptation of the article in the Country Hall of Fame Museum’s Encyclopedia of Country Music (Oxford University Press). The entry reads:

Jimmie Rodgers’s role in country music can scarcely be exaggerated. At a time when emerging “hillbilly music” consisted largely of old-time instrumentals and lugubrious vocalists who sounded much alike, Rodgers brought to the scene a distinctive, colorful personality and a rousing vocal style which in effect created and defined the role of the singing star in country music. His records turned the public’s attention away from rustic fiddles and mournful disaster songs to popularize the free-swinging, born-to-lose blues tradition of cheatin’ hearts and faded love, whiskey rivers and stoic endurance. Although Rodgers constantly scrabbled for material throughout his career, his recorded repertoire was remarkably broad and diverse, ranging from love songs and risque´ ditties to whimsical blues tunes and even gospel hymns. There were songs about railroaders and cowboys, cops and robbers, Daddy and Mother, and home—plaintive ballads with all the nostalgic flavor of traditional music but invigorated by a distinctly original approach and punctuated by Rodgers’s yodel and unorthodox runs, which became his trademarks.”

Jimmie Rodgers in obligatory cowboy garb

The Carters

The Carter family represents a turning point between the rural music of the nineteenth century and that of the twentieth. Their music is the prototype from which modern folk and country music evolved. Contrary to common belief, modern folk music (Pete Seeger; Peter, Paul and Mary; the Kingston Trio; Bob Dylan; Joan Baez) does not have an unbroken historical thread of evolution from the earliest days of America. Modern folk music is an offshoot of country music in the early part of the twentieth century.

The Carter family was instrumental in defining the modern parameters of early folk and country music. Their music marks a switch from emphasis on the ‘hillbilly’ instruments used by rural white musicians to a concentration on the vocals. The vocal delivery includes the rough but attractive vocal harmonies modeled after gospel singing and found in country music to this day. A second feature is shared with Vernon Dalhart, and that is the straight-ahead, unadorned rendering of the music. The nasal ‘twang’ found in the female vocals of the Carter family is also a feature that carried-over into modern country music.

In jazz in the late 1920s and 1930s, changes in the jazz rhythm section witnessed the replacement of the banjo as a chordal accompaniment instrument and the tuba as the instrument assigned to the bass line. The Carters, of course, at no time incorporated the tuba, but they did follow suit in supplanting the banjo with the more fluid, more rhythmically flexible guitar. Moreover, Maybelle Carter developed a style of guitar playing that became the standard in both country and folk music. The style, in which the melody is plucked on the bass strings and the chord is strummed whenever there is a pause in the melody line, is aptly called “Carter-pickin’.” Because Maybelle tuned the strings of her Gibson L-5 guitar lower than the standard pitch, the addition of a string bass was never necessary. It is a style of guitar work heard distinctly on the audio file examples, especially in the introductions. “Wildwood Flower” and “Keep on the Sunny Side” are two of the Carter’s best known songs, the latter becoming their “anthem.” The song has also enjoyed renewed popularity with its inclusion in the soundtrack to the film “Brother, Where Art Thou?” Note the stanza-refrain form, drawn from African American music, of “Sunny Side.”

The Carters consisted of A.P. Carter (Alvin Pleasant Delaney Carter), his wife Sara, and his sister-in-law Maybelle. The women were the primary singers, and A.P. often sang baritone or bass. Maybelle carried the brunt of the accompaniment although Sara often added her autoharp or guitar-playing to the musical texture.

The mainstay of their repertory was drawn from the hundreds of British and Appalachian folk songs collected near their homes in Virginia and Tennessee over the years by A.P. The songs drawn from the public domain include "Worried Man Blues," "Wabash Cannonball," "Will the Circle Be Unbroken," "Wildwood Flower," and "Keep on the Sunny Side."

A.P.’s early music training had been given to him by his mother, who taught him traditional and “old-time” songs on the fiddle. As an adult, he abandoned the violin but began to sing gospel with other family members. He met his wife Sara in 1911, when, as a traveling fruit-tree salesman, he heard her sing and play on her front porch. They married in 1915 and until 1926, they sang at local parties and social events while they earned their living at odd jobs. During this period he rejected a recording contract with Brunswick records. The company wanted him to record fiddle tunes and only fiddle tunes—an act A.P. regarded as being against his parents’ religious beliefs! By 1926, Maybelle had joined as a regular member of the group.

The Carters

The Carters’ break came at the recording audition set up by Ralph Peer in Bristol, Tennessee, in 1927. This is the same recording auditions in which Jimmy Rodgers was discovered! Several of the takes from the session were released as singles and sold well. Peer signed the Carters to a long term contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company label in 1928. The association led to the recording of their most important songs, and turned the trio into an act of national prominence. The Depression put a significant crimp in the group’s ability to earn tour money, and during the early 193os the group was reduced to performing in Virginia school houses and covering lost income with odd jobs. In 1936, they switched to Decca records. The following year, they signed lucrative contracts with radio station XERF in Del Rio, Texas, as well as several other stations along the Texas-Mexico border. Mexican stations were not governed by American law, and their transmissions were strong enough to assure that Carter Family broadcasts could be heard nationwide in the United States.

Marital strife wreaked havoc upon the group. By 1932, A.P. and Sara’s marriage was coming undone, and they separated. As the Carters finally resurrected their career, with the result of an upturn in the fortunes of Decca records, the marriage fell apart. They divorced in 1939. The group continued to perform until 1943, when Sara decided to retire and move to California with her new husband, A.P.’s cousin. Maybelle decided to record and tour with her daughters Helen, June and Anita. June, of course, married Johnny Cash. A.P. returned to Virginia, where he ran a store.

A.P. and Sara decided to reform the family with their grown children in 1952. Although their concerts around their new home in Mace Springs, Florida, attracted a record contract, newly recorded songs did not sell and the group disbanded again in 1956. A.P. died in 1960. In a final gasp, Maybelle and Sara reunited in 1966 to play a series of folk festivals and even to record for Columbia records.

The importance and influence of the style of music developed by the Carters cannot be understated. The music was one of the important starting points for Bluegrass and also provided the model scaffold for the modern country song. The echoes of a musical texture dominated by Gospel inspired vocal harmonies and backed by Carter-style guitar are still significant. Musicians who have clearly been influenced include, to name just a few, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Bill Monroe, the Kingston Trio, Doc Watson, Bob Dylan, and Emmylou Harris.

Audio Files! “Wildwood Flower” and “Keep on the Sunny Side”

A scarier and more famous photograph of the Carters

Texas Swing, Honkey Tonk, and the "Nashville Sound"

Bob Wills and "Texas Swing"

One of the early pioneers of country music was Bob Wills and his group, the Texas Playboys. Wills' grandfatehr and father had both been champion fiddle players, so his fate as a musician was pretty much sealed from the outset. As he grew up, he absorbed the influences of the music he heard around him, including the African American worksongs he heard working as a child in the Texas cotton fields.

Wills' music is a melange, and that is precisely what makes it so important and so interesting. The vocal delivery does not differ from the straight ahead, unadorned vocals found in the music (on the CD) of Vernon Dalhart's famous "Prisoner's Song." Will's incorporated the English and English-based American fiddle tunes he learned on his instrument, but he also added in Blues elements, the two-step from ragtime and the Fox Trot, and the "swing" of Swing. His metric treatments are dynamic and unusual. The stanza portion on non-Blues tunes is invariably a two-step, but the bridge section switches to the four count of Swing. The forms of the non-Blues songs are usually AABA, the form most frequently found in Swing. Often, Wills modifiies the form to ABA.

Wills is the first to incorporate the Hawaiian guitar, today called the "Pedal Steel," an instrument which has become the defining one of country music. Curiously, the pedal steel guitar is heard still only in Hawaiian and country music. The most famous of his pedal-steel players was Leon McAuliffe, a master by any standard in any time.

Wills' band was a large one by today's standards but small in comparison to contemporary big-bands. The group usually numbered around twelve members. It was first and foremost a dance band, and took to the stage in cowboy outfits. The talking you will hear in the audio files is Wills, as is the fiddle playing. The talking is annoying at first hearing, but after repeated times, one comes to love it! The talking is Wills accomplishing the two crtical two tasks of the leader--he is announcing to the audience the song title and he is cueing his soloists.

The "sound" of Wills' music has served as a model of so much music that would follow that the sound is familiar to us. The remarkable aspect of the music is its successful and modern mixing of stylistic elements and is this music first emerged: the 1930s! The overall impression is urban hillbilly two-step that somehow cooks. The instrumental parts are truly remarkable. Careful listening reveal that the musicians playing obbligato parts are not playing country, they're playing jazz, and incredibly good jazz at that!

Despite the commerical nature of the music, which was intended dancing on Saturday nights in large ballrooms, there is are several features that prevent it from becoming just a curious and short-lived music style. For one, many of the songs go past their dance functions and have the power to tug at the heartstrings. At the very best, the musical quality of the melodies makes some of the songs great ones; at the worst, the melodies are, at least, well-crafted. His musicians were all top notch, and their obbligatti and solos, which Wills left up to each player, are "listening-quality" jazz rather than background music. As times changed, large groups became financially more difficult to maintain. As noted, Wills' music served as a model for later country. Since the music was intnended for the common man, it is easy to see how the music could also be regarded as the very first in the "honkey-tonk" style.

Commentary on Selected Songs

"Rose of San Antone"-one of Wills' best known pieces after "Milk Cow Blues," it features the the metric shift from two to four described above. It's form is ABA. Listen to the pedal steel in the background!

"Milk Cow Blues"-the best known of Wills' songs, it is a white, Texas take on the twelve-bar blues. Wills is quite talkative on this track and his "voice-over," which is done live, is an outgrowth of the barn-dance call tradition, a tradition in which Wills' was immersed as a fiddler.

"Faded Love"-probably the very best of Wills' songs and, as effective as it is in this rendering, its full potential to break one's heart remained unrealized until Patsy Cline's version fifteen years later in the 1950s. Like the "Rose of San Antone," "Faded Love" also has a metric shift in the bridge. It is not as obvious as that in "Faded Love" because the bass, the part in which the shift occurs, does not play every measure in a uniform four-count. Cline's version should be included in the listening for comparison.

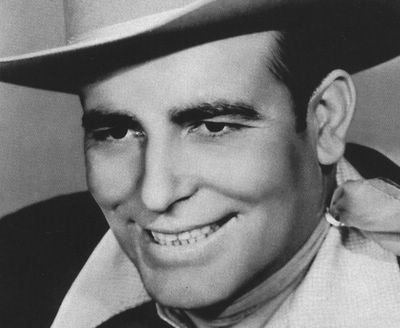

Bob Wills

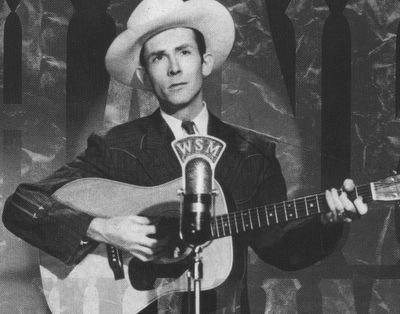

Hank Williams: The Tragic "Honky Tonk" King

Hank Williams career at the pinnacle spanned only a few short years, based on his recording dates, from around 1949 to 1952. Unlike many of the artists that came before him or were his contemporaries, Williams was not a folksong collector/singer but the author of his own music. His greatness as a songwriter lies in the quality of the music and the texts and what they reveal that is universal to us all. His greatness as a singer is that his delivery can't hide his pain. He sings the lifestyle he led, and the best assessment of it, now a cliche, is that Williams "moaned the Blues." His was not a pretty voice, but it was genuine.

Williams' primary adversary was himself, embodied in demon alcohol and its resultant tempations, women. He was a drinker of unimaginable dimensions. His affair with alcohol might have begun as measure to ward off the pain of spina bifida but, in short order, it took on a life and meaning of its own. Although Williams could stay sober for months at a time, when he went off he went off, and the binges often lasted three or four days or more. It could be argued that alcohol gave him the material that made his songs and career possible, but alcohol also cost him dearly. At one point, he was banned from the stage at the Grand Ole Opry after drink began to interfere with his professional obligations. Alcohol nearly cost him his marriage, being likely the underlying reason for nearly all, if not all, of the strife. Finally, alcohol cost him his life. He died quietly at age 29 of alcohol-induced congestive heart failure in the back seat of his Cadillac as he was being driven to a 1953 New Year's Eve gig.

Williams' music drew upon the hillbilly and honky tonk traditions, and here it stands in some regards as a more intimate, smaller scale, less formal extension of the beer-stained, blue collar, honky tonk music pioneered by Bob Wills. If you wanted to listen to Wills, you put on your best cowboy shirt, hat and boots, put your entire paycheck in your pocket, and prepared to step high, step out, and two-step. To listen to Williams, you found a dark corner in a dingy bar and ordered another round to cry into.

Williams also drew upon Gospel and the Spiritual, as "I Saw the Light" and a series of morality stories under the name "Luke the Drifter" attest, as well as Blues and the popular song traditions of Tin Pan Alley. The Tin Pan Alley tradition is most evident in Willams' observations of the shortcomings and conflicts of domestic life, which invariably describe real problems in humorous terms.

The music may be divided into categories on the basis of the character of the songs. Regardless of their intent, however, the songs always convey the sense of life struggle from the point of view of someone who is living it. Even the humor songs contain subtle elements of this pain. Williams' songs are always couched in the vocabulary, experience, and circumstance of the lower middle class. His central figure is the working man who has worked very hard for the little he has. Many of his songs talk about home and love, the search for and loss of love and, Lord forbid, what can happen if one actually finds it!

His work included upbeat, humorous, dry-witted, and irony-laced tellings of hard luck stories of life and domestic relations. This category embraces songs like "My Bucket has a Hole in It," a general, almost non-sensical story in the vein of the old Grand Ole Opera adage "if I didn't have bad luck, I'd have no luck at all!" "Move It on Over" tells the story of a husband whose misbehaving ways force him to share the doghouse, YET AGAIN.

Williams' love songs, or more accurately, his songs about love gone wrong ("you don't love me no more") are among his most intimate. Like the ballads of Patsy Cline, these songs should carry a warning label that repeated listening causes permanent emotional damage in the listener. "I Can't Help It (if I'm Still in Love with You)," "Cold, Cold Heart," and "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry" are among the best examples. As a side note, "I Can't Help It" and the humor song "Hey Good Looking" were recorded a few hours before I was born. His heartbreak songs are the most obviously autobiographical, the result of a marriage strained by the clash of two strong wills and William's legendary alcoholism.

As noted, a third type of song was issued under the name of "Luke the Drifter." These morality vignettes reflect American values of home and faith as by expressed by someone who might have seen them, or the semblance of them, around him, and longed for an ideal that he knew in his heart was unattainable and unreal, at least for him. These songs contain the same simplicity and intensity as the melodramatic movies of the period. For this reason, they were not easy listening, then or now.

Williams' music is drawn stylistically from many areas, but it never gets too far in sophistication from the basic models of the Spiritual, the Blues, and hillbilly song. His band is a fine one and features stand-up bass, rhythm guitar (Williams), pedal-steel guitar, and fiddle. Drums are conspicuosly absent. The instrumental roles are subservient to the vocal part, which is solo, though introductions, fills and breaks permit the band members to set forward. Like urban Blues, most songs feature an instrumental rendering of one fo the stanzas. Like the music of Bob Wills, the musical content of the instrumental parts are left to the players, but their entrances are carefully choreographed not to interfere with or overshadow the singing. Like the music of Wills', the two-step supplies the metric underpinning. Williams' band is so good that they manage to hide the single weakest instrumental link--his rhythm guitar. Doubtless adequate when sober, he was often too drunk to be effective, as in-house pilot tapes that he made as a soloist with his guitar reveal.

One critical point must also be made here. Most music to this point in time was recorded with everyone playing at once without overdubbing or "punching-in" recording techniques. If you were a musician, you could not hide in the studio, as today, you had to have the "chops." The fact of recording all the members of the band at once also explains the tendency toward simpler musical textures and fewer instrumental pyrotechnics. The emphasis was placed upon strong rather than complex melodic parts. In the studio, the best of several takes was the one that was turned into the record. Mistakes remained for posterity, but at least the performers sounded in live performance as they did on the record. Because the singer's best take was not always the best take for other members of the band, some rather horrific solos (at least if it was your solo) have been preserved for all time, as in Scotty Moore's unsuccessful experiments on "I Love You Too Much." Everytime I hear the solo I am reminded of the words of the TV commercial for the footage of airplane disasters: "be there when it all goes wrong!"

These tunes fall into the category of dry-humored, light-hearted songs of blue-collar life that pepper Williams' output. Like nearly all his songs, they are drawn from his tempestuous relationship with his wife. She may be seen in the photograph on the contents page to this lecture. Two songs chronicle the down moments in domestic life. "Move It On Over" Tells the story of a repeat offender, home drunk and late once more. "Mind Your Own Business" is a less than diplomatic approach to the neighbors. "Hey, Good Lookin'" is a hillbiily pick-up line, and the song is the likely model for later, considerably less original or humorous tunes like "If I Said you Had a Nice Body, Would You Hold It Against Me?" "My Bucket Has a Hole In It" is a song of generalized but nonsensical complaint. At first glance, it is the lament of the someone run out of beer, but in short order one realizes he's really singing about the guy whose lot in life is always to come up a day late and a dollar short, in brief, the working man.

<>

"I Saw the Light"seems like a white Spiritual and, for all practical purposes, it is. Its origin, however, is a quite different from a religious event. As the story goes, Williams got drunk and lost in the woods, where he wandered about for some time. He finally came to the edge, where he saw the lights--the runway lights of an airport! The experience was the spark of the song, or at least its title.

"I Can't Help It (if I'm Still in Love With You)," "Cold, Cold Heart," and "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry" are three songs that are among his best known after "Your Cheatin' Heart" (on CD). These songs are the most emotive and powerful of all his songs. They are all love songs, again likely drawn from experiences with his wife (neither were faithful). They sing from the perspective of the desperation of rock bottom. "I Can't Help It" is a song of loss. She was the love of his life, and there is no getting her back--she's gone for real and she's gone for good. The love songs add a deeper dimension and a note of very real pathos to Williams' body of honky-tonk songs.

Hank Williams

The Nashville Sound: Patsy Cline, Country's "First Lady," Then, Now, and Forever

Patsy Cline was born Viriginia Patterson Henderson in Winchester, Virignia in 1932. From an early age she was musical, often entertaining the neighbors with her singing. Her early devotion was to country music, and her career started singing at local venues such as country fairs. Her marriage was a very unusual one, not only in that her husband Charlie Dick stayed home with the kids, but that she felt free do do as she pleased, discreetly, with regard to other relationships. Much of the heatbreak in her songs likely did not originate in her marriage.

Like the music of Hank Williams, Patsy Cline's music may be categorized by type. Like Williams' work, a portion of her songs were designed to sell records and, as a consequence have an upbeat and often humorous irony to their story lines. These songs tend to show the greatest diversity of stylistic and hence popular song influences, ranging from early rock 'n' roll to "white" Blues to jazz to Latin elements such as tango. A second category, the one for which she is remembered, consists of the ballads.

Unlike Hank Williams, Patsy Cline did not write her own material. Her greatness lies in her ability to interpret songs, to infuse them with intense emotion. Curiously, the body of her work could not really be described as country. The arrangements and song choices were the product of the "Nashville Sound," a movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s to make the product as slick, appealing, and saleable as possible. For Cline, this treatment meant carefully carefully detailed, varied, and rehearsed instrumental backgrounds that featured some of the very best studio musicians but also featured such overblown, at least for country music, features as string sections.

That movement to "refine for sales" continues today, and the fact explains why so much of contemporary country music is watered down in content, intent, and style. The "star-making machine" begun in the Patsy Cline era is in full bloom today.

Cline herself initially rejected many of the songs she was asked to sing as being too "pop" and not enough "country." Indeed her music probably falls more into the popular song genre than it does into the country genre. Yet some of the songs at which she first balked at singing are now regarded as her best. Curiously, every recent MTV poll places Patsy Cline as number one in the list of important country singers. Her singing and interpretations are so intense and so fine that no one even seems to notice that her music isn't country!

Cline's first important song was "Walkin' After Midnight,"released in 1957. She was voted "Female Artist of the Year" in 1961 and 1962, and her song "I Fall to Pieces" was voted "Best Song" in 1962. Her version of "Crazy," a song written by a very young Willie Nelson, is to this day the most requested juke box song.

Cline died in 1963 when the small plane transporting her home from an appearance crashed in bad weather. Unlike so many other important American entertainment icons, she would be remembered for her contributions even if her life had not been tragically cut short. In an incredibly sad and eerie stroke, two of her greatest "torch song" ballads, "Sweet Dreams" and her version of Bob Wills' "Faded Love," were released posthumously. Compare Cline's version of "Faded Love" to Wills' original.

A young Patsy Cline in her cowgirl outfit!

A later photo of Patsy Cline taken after her disfiguring 1961 car accident

<>Commentary on Selected Songs

"Faded Love" (composed by Bob Wills), "Crazy" (composed by Willie Nelson), and "Sweet Dreams" are among Cline's finest torch songs. "Faded Love," of course, is Cline's take on the Texas Swing tune by Bob Wills. As noted, "Crazy" is the most requested song on American juke boxes to this day. Like so much of Wille Nelson's later music, it shows jazz ballad influences in its progression and Swing influence in its AABA form. Ray Charles possibly drew upon the flavor and arrangements of these tunes, and especially "Crazy," in his songs "Georgia" and "I Can't Stop Loving You." The influences echo still in Vince Gill's "Nobody Answers When I Call Your Name" and "Ain't No Future in the Past."

"Honky Tonk Merry-Go-Round" is a clear descendant of the music of both Bob Wills' and Hank Williams. It is a two-step, and uses the same instrumentation as Wills and Williams. "I Fall to Pieces" derives its bass line from 1930s "jump" bands, pared down Swing groups that began in the 1930s. It retains the four count of blues and Swing.

"Last Night I Dreamed" and "Try Again"are tunes clearly derived from jazz yet are not jazz. One could reasonnably categorize them as "lounge" music. They are typical of the commercialization of jazz by Nashville record companies and Hollywood producers in the early 1960s. The edge, drive, and art of real jazz have been gutted in order to make them commercially attractive. Despite fine performances by Cline and her musicians, the songs are what they are. If you like Patsy Cline, you hardly notice.

"Stop, Look, and Listen" derives its title from the "X" shaped signs that used to adorn railroad crossings. The words of warning were printed on the cross bars. The song is a rock 'n ' roll of 1950s vintage, and reminds one of the type of music produced at the time by Bill Haley and the Comets. As in 1950s rock 'n 'roll, country musicians experimented with hybrid styles. "Strange How You Stopped Loving Me" is a tango!

Patsy Cline album photo. She is wearing the same outfit as in her now famous video-taped Opry perfomances. In later years she traded the cowgirl outfit for the "housewife" look.

The last photograph of Patsy Cline taken the day before her death

The two-step has its origins in marching band music that came into popularity in the middle of the nineteenth century. Military use for music dates to Medieval Europe and beyond. Here the music furnished by drummers and brass players at the head of the column not only fired up the troops to fight, but also hopefully would unhinge the enemy and produce a rout. The military band came to America with the earliest colonizers. Its iconography is deeply ingrained in Americana and can be seen in depictions of tattered Revolutionary-War fifers and drummers as they bravely march and play through the terrible battle.

The rise of the marching band as a critical civic and musical institution occurred in the 1860s. The establishment of the municipal marching band in nearly every town in America was more than coincidental. America was at war with itself, and the marching band not only fulfilled the military needs of giving each battle group its identity, but also served the critical function of keeping up the spirits of the families left behind at home. The idea that everyone loves a parade is probably still valid, and the parade certainly served to salute those local boys willing to step forward to the defense. Parades also offered a visual self-appraisal of the strength of the fighting unit derived from the specific region, and the more grim opportunity for the community to take stock of those soldiers who did not return. The Civil-War embrace of the marching band left an indelible mark on American public-school music education, and until only very recently, the music lessons offered were only to train members of marching and stage band. Only in the last decade and a half has the American public school expanded its outlook to include training on symphonic instruments such as the violin.

Marching band music attained art music status with the marches of John Philip Sousa. The rousing marches of Sousa and his contemporaries resonated deeply in the American psyche, giving America a musical identity and becoming almost the “official” patriotic music of the country. We were “Yanks,” and now we had the music to prove it! Sousa’s music reflected the strength of the new national Union of North and South, but also issued a dare to all outsiders to “knock the chip” off our collective shoulder. America had arrived.

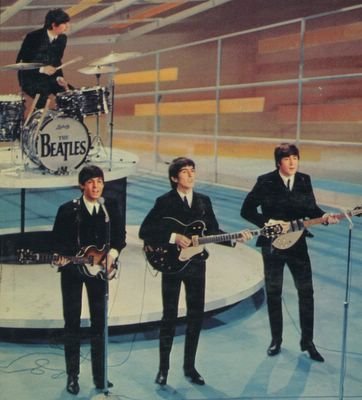

The marching was an important part of the musical culture of St. Louis, the city in which Scott Joplin lived and worked. Had a different style of music predominated in St. Louis, Joplin’s music might have been far different. As it worked out, Joplin’s advanced musical training, his need to celebrate his African-American origins and culture by incorporating the musical elements of them, and the march came together in the one of the earliest advanced genres of American popular instrumental music. His music was an important springboard to other later genres, and the legacy of the two-step would echo as one of three means to organize the metric aspects of American popular music in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The two-step is found in Country and Folk music but is not limited just to those styles. It is also a component of the music of American musical theater and some commercial popular music, including music of such British “invaders” such as the Beatles.

Identifying the Two-Step

The two-step exists within a four-beat framework, but it places the accents on the first and third beats to give the impression that measure has two instead of four beats. This accenting likely had practical origins—it would be nearly impossible to march to a fast four-beat pattern, and a slow four-beat pattern would certainly lack the power to rouse the high spirits of the march. Instead, the steps of marching band members had to occur on every other beat. In listening, one could count four within the two-beat accent structure, but the rate of the four-count is generally so fast that it is not comfortable.

The two-step is expressed first and foremost by the bass. The quintessential treatment is called “alternating bass.” In this process, the bass instrument (tuba in marching band, “stand-up” or electric bass in Country and Folk music) plays alternately the root and the fifth of the chord. In Folk music that lacks a bass instrument, the guitar both strums the chord and alternates the bass. The specific theoretical details of root and fifth are not critical to your recognition: the sound is so common that you will recognize it immediately in the audio files.

Listen to the demonstration of the alternating-bass accompaniment on single guitar and then contrast it to the excerpted audio files. I have incuded both duple-meter and triple-meter two step treatments. The triple-meter concept comes from the "waltz song," a tradition of song brought to America with the wave of European immigrants in the late nienteenth and early twentieth century. "Take Me Out to the Ball Park" is the triple meter two-step.

The two-step bass work shines clearly through all of the musical examples, whether or not alternating bass is specifically stated. A curious contrast, completely characteristic of the music of Bob Wills, is found in the relationhip of the rhythm guitar and the bass. Here the guitar strums the chords in the four-beat pattern but the bass plays a two-step. Note the quasi- “Carter-pickin’” in Johnny Cash’s guitar work, a feature that is not surprising when one considers that he married one of the Carter girls. Cash's guitar playing does not quite meet the full mastery of the playing of his mother-in-law. The guitar work of Woody Guthrie, however, does very successfully carry on the tradtition of Maybelle Carter's picking style.

Suggested Listening

“Alternating Bass on Solo Guitar”

John Philip Sousa, “Stars and Stripes Forever”

Scott Joplin, “Maple Leaf Rag”

Gene Autry, “Blueberry Hill”

Bob Wills, “Going Away Party”

Johnny Cash, “Let the Train Blow the Whistle When She Goes”

Vince Gill’s “Kindly Keep It Country”

Two-Step and Four-Beat in the Larger View

The choice of metric organization is not only critical to establishing style but also to realizing that style. Inherent, also, are other features such as statements of cultural identity and the practical need to create a certain musical effect.

As you have learned, Country music springs from the same common nineteenth-century sources as Blues, yet it is very different. Country music shares some of the same stanza forms as the Spiritual and many of the same scales and “blue notes,” yet it is very different from Blues. Part of the reason may be ascribed to the “formality” of the parlor song, a feature derived from high-flown European piano music of the nineteenth century. The formality is also a significant component of ragtime. Another feature is that Country music remains in its essence closer to the hymn, retaining an “angularity” that is not found in Blues. This angularity can contribute to the “hee-haw” quality of some country music, a point often used by its detractors to mock it.

The departure of Blues and Country in metric organization can be further found in intended usage. Blues grew from the field holler and the Spiritual, but it origins can be traced even further back to polyrhythmic drum-dancing. Drum-dancing was a component of African but not European culture. In this music, the beat cannot be spaced in time to a relaxed distance, but must be continually stated in order to serve as a superstructure in creating polyrhythm. In some Spirituals, rural Blues, and early urban Blues, this need translates as the use of the bass notes, stated on each of the four beats of the measure or count, as a drum beat. In later Blues, modern jazz, and rock, the bass would be permitted to wander from a single, repeated note to make simple melodies, but the statement of a bass note on each of the four beats would be retained. In addition to the files given below, listen to both Chuck Berry selections on your CDs. In each of these different audio examples, take note of the relentless four-beat backbeat. Also note, especially in the chuck Berry tracks, that the four-beat count is infectious and compulsory, not optional.

Suggested Listening

Walking Jerusalem

Robert Johnson, “Love in Vain”

Muddy Waters, “Standin’ Around Cryin’”