Monday, April 17, 2006

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

Contributions of the Ancients

Survivng instruments, depictions of musicians in art, fragments of music score and, later, writings on the subject offer our only insight into the music of the ancient world. Even the hard evidence in hand is not helpful; scholars still work to decipher the music notation. Little is known, then, about how the music of the ancient world actually sounded. Even with its limitations, however, the evidence affords authentic glimpses into the life, culture, and music of very distant times.

The Singer of Amon, Zedkonsaufankh, Plays the Harp Before the God Marmakhis, Egypt, New Kingdom (c1400 B.C.) Painted Wood (Louvre)

Alkiaos and Sappho with Lyres,

Greece, Detail red-figure Clay Vase

(c450 B.C.) (Antiken Sammiun, Munich).

Throughout the intervening centuries, artists have made drawings, by studying ancient renderings, to identify the instruments imortant to the ancients and to show their aspects. For the Greeks, the lyre, the kithara, and the aulos were central to music-making. The lyre was a plucked string instrument whose invention has been ascribed to Apollo. Its basic acoustic principle exists today in both the harp and necked-string instruments such as the guitar. Another ancient Greek instrument, the aulos, featured a double reed. The modern oboe is the instrument that most closely resembles it in its properties. The two instruments, along with the kithara, a close relative of the lyre, were among the most important in ancient Greek music. Drums and pipes were also known, but the lyre, with its associations with the revered poet, and the aristocratic aulos remained central to Greek music.

aulos

lyre

Western culture does not begin in ancient

The subsequent entries identify the most important contributors to the scientific study of music and the formulation of a music theory discipline. They also address the powerful philosphical polarities at work in our species, and hence our music. The entries describe the contributions of each figure, and the overview of the ancient Greeks will serve as a portal into the study of music of later times.

The earliest contributor to a systematic, scientific, and arithmetic study of music was Pythagoras or, more likely, the members of the cult that surrounded him during the sixth century B.C.E. In the view of Pythagoras and his followers, numerical ratios could be applied to explain the natural phenomenon of the universe. The concept that all aspects of the universe were regulated by numbers and their ratios, called harmonia, informs the general approach of the ancient Greeks to their world. It at once embraces early arithmetic and the pragmatic and logic-driven methodology that would profoundly inform Western civilization, especially in the late Medieval formualtion of Humanism.

Pythaogoras' exploration, or more accurately the explorations by members of his cult, of fundamental realtionships of sound led to the generation of the modern natural major scale. To this end, the investigation moved forward using a purpose built "musical" instrument called a monochord. The monochord consisted of a single long string pulled taut enough to produce sound. He divided the string in consecutively smaller ratios by damping measured portions of the string. For example, the first division, in which half the string was stopped from vibrating, yielded a pitch higher than the original in a relationship called in modern terms the interval of an octave.

One can experience first-hand the phenomenon by first pressing a key on the piano and then pressing the correspondent key elsewhere on the keyboard. Similarly, the guitar will yield the same experience if one first plucks a string without placing a finger on the neck. To hear the octave, one squeezes the string at the twelfth fret and plucks again.

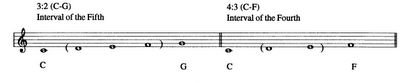

Two other divisions of the monochord critical to Western music are the next two ratios in the sequence of division. These ratios are 3:2, called the interval of a fifth, and 4:3, interval of a fourth. The two intervals became critical later in Western music in the division of the octave and the evolution of harmony. In a stepwise sequence of notes beginning on C, G is the note that relates to C as its fifth (C D E F G). Note that the C note is counted as "1." In the same sequence, F is the note that relates to C as its fourth. Conversely, the C note can also relate as the fifth of the F note if the F note is used as the starting point (F G A B C). Likewise, C note can relate as the fourth of G note if the G note is used as the starting point (G A B C).

By using the three ratios (2:1, 3:2, and 4:3) in subtraction and addition, Pythagoras and his follows were able to generate the pattern of notes known today as the natural major scale, a series of notes that begins on the note C and is bound at the lower and higher ends by the octave. The notes are, in order from lowest to highest, C D E F G A B C. In his construct using ratios, the E and A notes sound sour to modern ears.

The process of addition and subtraction embodies the use of fractions. For example, Pythagoras was able to determine the difference between the interval of a fifth and the interval of a fourth by converting them to fractions and subtracting one from the other: 3/2 - 4/3 = 9:8. The ratio 9:8 expresses the interval of a second, precisely the ratio of the scale notes F and G but also the ratios of C-D, G-A, and A-B. Although also consecutive, the notes E-F and B-C do not exist in the same ratio as F-G. The intervals between E-F and B-C represent the smallest between notes in Western music, are called half-steps, and are reckoned in a ratio smaller than 9:8. All Western musical instruments reflect the half-step in their construction. The distance occurs in the movement on the piano from a white key to the nearest black key or from one fret to the next nearest on the neck of the guitar. The pattern of whole steps and half-steps found in of Pythagoras' scale, and hence the modern natural major scale, is w-w-h-w-w-w-h.

The remaining intervals of the second (C-D, D-E, F-G, G-A, and A-B) occur in the ratio 9:8 and are called whole steps. Other cultures, especially those of the

The octave pattern of notes identified by Pythagoras stood for centuries as the model to be taught in music education, though the natural major scale did not come into actual common use until the mid-sixteenth century! The natural major scale is still in use today as the starting point for musical composition and musical training.

In identifying the tones of the natural major scale and assigning ratio values to them, Pythagoras formulated the model that later Western musicians used first as a standard in teaching and finally as a standard in making music. The exclusion of microtones from practical music did not occur in ancient times, but somewhat later as the musical liturgy of the young Church evolved a European, rather than Middle Eastern, identity.

Scales used by in early Christian times in Europe did not replicate the natural major scale of Pythagoras but derived from it, using the same fixed pitches in sequences starting on different notes (i.e. D E F G A B C D or E F G A B A D E). The resulting scales are called modes . The use of a single set of eight, immutable pitches are critical in the development in ninth-century

The Doctrine of Ethos was the result of the observations and thinking of two fourth-century B.C. E. philosophers, Plato and Aristotle. They believed that music had an effect not only on behavior, but also upon shaping personality. Hence, listening to certain scales and types of music could determine the basic characteristics of a person. For example, continued exposure to martial music could produce a soldier. The Doctrine of Ethos seems a little extreme to the modern reader, yet music can have immediate though temporary effects upon the listener. Music can calm, stimulate, and affect moods.

Aristotle and Plato also felt strongly the music was necessary to proper and complete education. They regarded music study as belonging to the sciences rather than to the arts, a feature that would be retained until the Renaissance. The study of music also came with an admonition: music should be studied in moderation. The development of virtuostic skills was not regarded as desirable since it came that the cost of the development of other areas of expertise and learning. Today their thinking is reflected in the inclusion of music study as part of a broader education, yet it is regarded, as is the study of other arts and literature, as essential to the development of personal refinement and human enrichment.

The next great strides in Western music came with the codification by Ptolemy and Cleonides (c.2th century C.E.) of octave species. An octave species is an eight-note scale. Ptolemy called these octave scales "tonoi." Cleonides called his codification the "system of octave species." Quintillianus would also offer similar octave species in the 4th century C.E.

The octave species of Cleonides and Ptolemy differ from the model offered by Pythagoras in several respects. They are not generated by monochord division but based upon observation of actual musical practice. Although they utilize the same pitches identified by Pythagoras, the pattern of whole steps and half-steps differs from the scale of Pythagoras. The tonoi may be played on the white keys of the piano, with each consecutive mode or octave species beginning on the next white key. Names, such as Dorian, Phrygian, and Lydian, associated with each scale likely refer to the poetic and musical practices of various ethnic groups. The same names were applied to the Church Modes, but it is important to note that the names found in the tonoi do not describe the same scales in the Church Modes. In the following exampel, each consecutive mode or octave species is played beginning on the next white key.

The fixed pitches of Pythagoras' scale represented the first step toward a scientific study of music. His scale's sour third and sixth notes (E and A) highlighted a problem that arose in the difference between the purely arithmetic measurement and the pitches that actually occurred in practical music. The position of Aristoxenus (c.late third century B.C.E.) stood in direct opposition to that of the cult of Pythagoras.

His approach advocated the adjustment of pitch on the basis of aural perception. To his thinking, the singer or player could adjust the note to sound "in tune" even if the note fell outside the Pythagorean model. To back up this license, Aristoxenus cited a new mathematic discipline developed by Euclid and others, geometry. Geometry could prove measurements smaller than those that result from the addition and subtraction of fractions. Aristoxenus cited the capability of geometry to measure more precisely not only as a means adjust pitch, but also to prove the existence of the adjusted pitch. Foremost to his music thinking was that empiricism, that is aural perception, should determine where the pitch was sung or played.

Additional advances in music theory are found in Aristoxenus' description of the usable range of pitches from highest to lowest, which he called the Greater Perfect System, and his division of the gamut, which included notes in this range arranged in a stepwise order, into "tetrachords." Aristoxenus gave as his lowest note the A in the lowest space of the bass clef. The highest is the A note above middle C.

The Greek gods embodied characteristics of the human psyche. Two gods, Apollo and Dionysus, possibly represent polarities of thought and behavior particularly important to art and music.

Apollo

The other symbol associated with Apollo was the lyre. He used the lyre to instruct in the merits of music, regarded in the ancient world as a mathematical discipline, poetry, and dance in elevating the human soul (and character). He called men with his lyre to ephemeral communion with the gods. Later humanist thinkers easily transferred his meaning, and applied it to encompass justice, purity, intellectual pursuit, reason, restraint, sobriety, and dispassionate and objective empiricism (i.e. scientific method). More public ramifications include Christian morality, courtly chivalric code, civic responsibility, and civil order and law.

Dionysus

Although also a son of Zeus, Dionysus personified the sensual side of human nature. Also known as Bacchus, he was associated with the life-giving fluid component of nature such as sap, juice, and lifeblood, and with fertility. To this end he ruled the satyrs and Nature as the god of vegetation and fruitfulness, as in the display of nature's fertile regeneration in springtime. In the simplest human application, he represented wine and ecstasy.

The Gods and Polarities in Western Art

The states of being embraced by each god clearly represent two profound forces in eternal competition in human nature. In Western art and music, the forces could be interpreted, regardless of time period, in "Classical" or "Romantic" terms. Beyond the catch-all label "classical music," a general term which in the twentieth century has come to signify all art music from all periods of time that is not born of popular culture, music with clear classical influences contain certain characteristics.

Classical aspects in music are apparent, as they are readily in architecture and art, as clarity of texture and form, balance, symmetry, restraint, elegance, transparency of texture, and logic in the relation of the parts to the whole and the resolution of formal problems. Although classical music might contain powerful expressive elements, it is absolute in character, that is, its value is its reason for being.

By contrast, music that displays romantic traits deliberately seeks to strongly express or represent intense emotion. The music is often programmatic, that is, narrative in its telling of a story. It contains sharp contrasts, even excesses, of timbre, tempo, dynamics, rhythm, and texture. Programmatic or romantic music is often through-composed. Furthermore, elements such as motives or unusual harmonies in the music often symbolize an idea, character, state of being, or event. The impetus to compose is not the music, but the emotion it conveys.

Although the complexity or the character of a piece of music or art can depend on the state of technical sophistication of the medium at the time of creation, the classical or romantic spirit still shines through.

Monday, April 10, 2006

Greek Sculpture as a Model for Understanding Evolutionary Process in Western Music

The polarities of "classical" and "romantic" are, of course, embodied by Apollo and Dionysus. The adherence to one tenet or the other is not wholly determined by the creator, but often by the state of technical evolution of the genre in which in he works. The reality is apparent in the evolution of Greek statuary, and the nature of the process holds true for other art media including music. The cycle depicted in Greek statuary is repeated in Western music, and will become a touchstone.

There are three stages of ancient Greek sculpture, archaic, classic, and Hellenistic. The emergence of a romantic spirit in art or music, as in the sculpture below, assumes that there is an inherited starting point with regard to form and that the realization of the romantic spirit is ennabled by the technical progress in the medium. Finally, the classical or romantic spirit does not necessarily have to dominate a work; both can be present in varying degrees.

The earliest stage of Greek sculpture clearly draws upon the achievements of the Egyptians. The first sculpture, "Mycerinus and His Queen," is an example of Egyptian sculpture which dates from c2500 B.C. It is clearly representative, though the actual features are clearly idealized rather than reflective of how the characters actually appeared in life.

Mycerinus and His Queen

The straight-on frontal view of the king and the placement of his feet, one before the other, is retained in the second sculpture, the Greek "Kouros (Standing youth)," a work dating from c600 B.C.

Kouros

In the case of the Kouros, however, the placement of the feet represents a significant forward stride in engineering. The placement permits the statue to stand unsupported. The idealized rendering of the parts of the body, a characteristic of Egyptian art, is also evident in the Kouros. Egyptian artists represented the part of the body from its most typical angle, that is, the chest is depicted from the front, the arms and legs from the side, and so forth. The custom is not apparent in the example of sculpture, but is easily found in paintings and bas reliefs.

"Doryphorus" (the "Spear-Bearer") is a Roman copy of an original by Policitus dating from c450 B.C. It brings Greek sculpture into its Classic era. The musculature is carefully represented but, despite the extensive detail, the proportions are not accurate to life. Instead, the sculpture was guided by the aesthetic ideals of form, balance, and clarity. The result owes its posture to the Kouri and Mycerinus in turn, but its aim is the achievement of a high level of ordered beauty. Note that the sculpture is not truly freestanding.

doryphorus

Discobolus

Vestiges of Kouros are apparent in both "Aphrodite of the Cnidians," the female figure on the left, and "Hermes," the male on the right. Both works are Roman copies after originals by Praxiteles c330-320 B.C. The further refinement of the musculature is one clue to the coming Hellenistic Age, but the real signal is found in the softening of the posture so that it borders on sensual. Moreover, Hermes posture also conveys feminine characteristics. That the figures permit a sensual component shows a subtle breakdown in the tenets of classicism that otherwise inform the works.

Praxiteles: Hermes and Aphrodite

Yet, the romantic qualities of the scene cannot completely hide the classical components that inform it. As noted, there is the symmetry. The bodies, though the details are exaggerated in their development, still represent "ideal" rather than "real" or "natural" renderings of human form. The punishment, as dramatic as it is, does not convey to the viewer the true horror of death by serpent, but instead broadcasts punishment in a frozen, antiseptic, and rhetorical sense.

Lacoon

The "Dying Gaul," which dates from c230-220 B.C., brings home forcefully the darker side of romanticism. The scale of human morphology is toned down so that it is closer to that of the normal male. The subject is not presented in a glossed, cleaned up form. The soldier is dying, and every aspect of the sculpture realistically conveys the fact from the bowed head to the slight crook in the supporting arm. The viewer is drawn into his plight and can only wait quietly with him until the end comes.

Dying Gaul

The progression occurs in three stages. First, a model is abosorbed and adapted for use, as often as not by a newly ascending or emerging culture. Second, the absorption of the model is complete in the "classic" stage, the point at which the tenets of the new style are defined and all the technical problems to realization are resolved. In the last stage, virtuostic displays often result. Here the realization of the work and the technical mastery required supplant the content of the work. The tenets as defined in the classic apogee give way to deformation of those very tenets. Three segments of the progression record the rise and degeneration of a means of expression or style of art. The third and final stage of development, of course, gives way to new ideas, and the cycle begins anew. In the course of the history of Western music, the birth to death cycle repeats at least three times, with smaller similar cycles contained within the larger ones.

Sunday, April 09, 2006

Early Christian Music: Centonization and the Establishment of a Musical Liturgy

Christianity, of course, began in the

Christianity absorbed several critical concepts from its parent religion Judaism (Jesus, if you recall, was a Jew). First and foremost was the concept of sacrifice. For Jewish priests, the sacrifice and burning of lambs upon the altar was a demonstration of faith to God. In Christianity, the sacrifice entailed that of Jesus, the Son of God, upon the cross. Sacrifice, then, is moved to a central place in Christian belief and worship. A second Jewish element to be absorbed was the singing of the Psalms in the synagogue and home. Early Christians continued the practice (the Old Testament is shared by both religions), and the Psalms became the source of texts for Chrisitan liturgical music.

Centonization and the Establishment of a Liturgy

As noted, early Christian music worship practices derived from the Jewish tradition, the singing of Psalms in the synagogue and at home. The Christian musical practice of chant began as an improvisational one called centonization. In the process of centonization, common musical motives (short melodic fragments) are placed in singing end to end to build up a longer melody. The order of motives may be changed to accommodate the changing emotions and lengths of different texts. The process lives on today in Blues (see "Centonization, A Still Viable Process" in the supplemental lecture New Millenium). By the eighth century many of the chants had been sung the same way so often that they began to assume a fixed form.

The components of the worship celebrations became standardized between the second and third centuries A.D. There were two different types of worship, one for the monastery and the other for the public. Monastery worship is called the Offices and consists of services spaced throughout each twenty-four hour period at intervals of about four hours. Some of the names of the specific services come to us today as the names of special choral concerts such as Vespers, Matins, etc. The worship service for the public is called the Mass. It is also divided into two parts, the Proper and the Ordinary. The content of the Proper is specific to the holiday. Each day of the year is a holiday, that is, a day representing some event in the life of Jesus. The Ordinary is a portion that does not change. It includes the Kyrie, Agnus Dei, Sanctus, Gloria, and Credo. The five portions of the Ordinary are especially important to the study of music because they have been traditionally the focus of composers' efforts.

In the early centuries of the Common Era, Christianity spread quietly but pervasively throughout the

The

As in the

The underlying reasons are manifold for the emergence in the fifth to eighth centuries of specific European liturgies. First, direct Eastern influence was cut off when the Empire split. Second, the Fall of Rome in 467 was accompanied by invasions by hordes from the steppes of central

Each of the different groups met particular worship needs by developing its own melodies for singing sacred texts. The generation of new melodies involved new composition, but as often the modification of chants inherited from Byzantine worship. The dialects to emerge included Gallic in

Codification of the Musical Liturgy

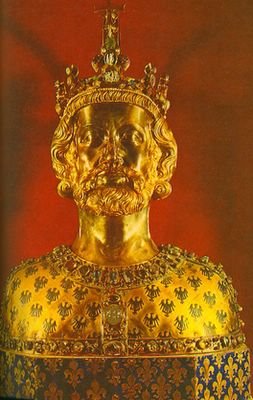

Pope Gregory II (c715 C.E.) desired that the chant repertory be codified, and he ordered that the chants be recorded in writing. Charlemagne (ruled as Emperor 800-814 C.E.) redoubled the efforts at standardization begun by pope Gregory and his father and predecessor, Pepin the Short. Charlemagne and Pepin the Short, before him, established the first great kingdom of

Reconciling the various dialects in codification presented problems, and ultimately the Gallic, Beneventan, and Ambrosian dialects were consciously supplanted by Old Roman rite. Mozarabic chant was not so easily displaced in

The process would have profound effects upon Western music. The completion of the codification process would give rise to Church prohibitions against changing the text or the notes of those chants included in the in the official sacred liturgy. Later musicians, for the most part monks, would find other ways to contribute to Church music, and their solutions would lead to the highest achievement of Western music, harmony.

Reliquary Bust of Charlemagne

Notation

Notation using heightened neumes represents a second step toward accurate notation. As in staffless notation, the singer was required to commit to memory the entire chant repertory as it was handed down by the older monks. Obviously, the neumes placed further above the text indicated higher pitches.

A critical forward step in accuracy came with the application of a horizontal line. The line represented a single, fixed pitch, and the singers could use that pitch as the standard against which to determine the relative location in sound of the other notes.

Staff notation, consisting of a four-line system, permitted the accurate notation of chant and, more importantly, the capability of a singer who did not know the chant ot render its notes correctly. The advance is recorded in Guido d'Arezzo's Micrologus (c1025) (Guido's contributions are assessed in subsequent Supplemental Lectures). A single but profound problem that remains today lies in interpreting the rhythm of the neumes.

Within chant, there are three classifications of the relationship of the text to the words. A syllabic setting is one in which one note is matched to one syllable. In a neumatic setting, several notes are matched to a single syllable. In a melismatic setting, many notes are sung to a single syllable. Florid melody typifying the last treatment is sometimes called a melisma.

Early Christian Thought On Music

Early church leaders and thinkers such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen, St. Basil, St. John Chrysostom, St. Ambrose, At. Augustine, and

Music in Medieval Europe also benefited directly from the writings of the ancient philosphers, arithemeticians, mathematicians, and music theorists. Their findings and empirical conclusions survived the tremendous political and social upheavals of the Fall of Rome in the writings of Martianus Capella and Ancilius Manlius Severinus Boethius.

Martianus Capella (early fifth century)

Martianus Capella was an important figure in the transmission of the knowledge of the ancient Greeks. His exstensive writings on the liberal arts had a significant impact upon the development of education in the West. He called the first three of the liberal arts, the verbal arts grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric, the trivium, or three paths. The remaining liberal arts consisted of the mathematical disciplines, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and harmonics. The mathematical arts were called by Boethius the quadrivium. The last of these, harmonics, consisted of the system of ratios in the intervals between musical pitches. Hence the study of music, albeit in a scientific form, became established early as a critical component of education.

Manlius Severinus Boethius (c480-c524/6)

Boethius was a Roman theorist. His compendium, De institutione musica (The Fundamentals of Music), became one of most important and influential documents of the Middle Ages. Boethius compiled is multi-volume work from the writings of other authors, most notable among them the Greek sources of Nicomachus and Ptolemy. Of the five volumes, the first three conveyed Pythagorean findings and conclusions. The fourth volume derived its content from Euclid and Aristoxenus. The fifth, which was partly anti-Pythagorean, was drawn from Ptolemy. The contradictions among the volumes did not seem a point of concern to medieval readers.

Boethius' most original contribution, however, was his division of music into three categories. The first, musica mundana, explained the movement of the planets, the changing of the seasons, and the elements as evidence of an underlying, orderly numerical system that controlled all aspects of the universe. The second category, musica humana, explains the relationship of the soul and the body and its regulation.

His third musical type, musica instrumentalis, focused upon audible music, whether produced by an instrument or the human voice. Like the earlier Greeks, he used the ratio of numbers to explain the intervals between musical pitches as an orderly system and stressed the behavioral impact of music upon humans. To this end he regarded musica instrumentalis as a critical component of education.

As noted in the entry regarding Capella's contributions, Boethius named the four liberal arts that embraced the mathematical disciplines the quadrivium. Boethius' musica instrumentalis fit into the category of harmonics. His understanding of musical study was not that meant in modern terms, that is the study of singing or playing an instrument. Instead, he advocated the study of the relative nature of musical pitches. He maintained that the true musician was not the singer, who sings by instinct, but the philosopher-mathematician who studies, measures, and critically assesses the medium and the relationships of the sounds produced in it.

Medieval Developments

The Organization of Medieval Society: the Feudal System and the Church

Feudal government was an outgrowth of several different Roman client systems. At the foundation, the relationship of landowner and the farmer was simple: the landowner provided capital or, more often, protection, and the farmer paid taxes, rents, or both to the landowner. The tenet created two large classes, the lord and the vassal, and one smaller but critical peripheral class, the soldier. The clergy constituted a fourth class fundamental to society but not fundamental to the economic workings of the feudal system. The members of the landed class often descended from regional warrior kings but were also created by the bestowal of immunities. An immunity could be granted by the king.

The recipient of an immunity gained the right to rule over his landholdings, within the canons of civil and Divine law, but owed his ultimate loyalty to the king, the only person who could supersede his word in law. Since the king lived a considerable distance and was usually preoccupied by more pressing matters, the rule of the lord was, for all practical purposes, unchallenged. Landowners often unscrupulously added to their power by adding to their landholdings.

The Church also shared some portion of the power with the king and the lords. Divine law had its source in Christianity, and the officials of the Church were its administrators. In practical terms, the king could and sometimes did participate in making religious or superseded the Church entirely, particularly if the implementation of religious law had civil consequences. Charlemagne, for example, ruled with a free hand in all matters. His coronation as Emperor was meant to signal the coming of yet another Roman Empire, the

The Church and its properties played a significant role in the distribution of the Medieval population. Roman roads already created an interlaced highway system that permitted travel through

Vassals came under the control of the lord in a variety of ways. Some were successful free farmers who fell under increasing threat from foreign invaders such, as the Muslims who invaded

Aside from the nobleman and his family, the local Church officials, and a handful of civil administrators, the entire population of the fief existed in a state of servility. Although the nobility did not work for a living, they gainfully filled their time with war, high adventure, political intrigue, and sport.

The vassals divided into several distinct classes. The largest classes were the villeins and the serfs. Villeins were small farmers who surrendered their lands in exchange for protection but were not part of the property. By law, the villain could be taxed but only within the limits set by civil law. Serfs, by contrast, were bought and sold with the land, and their labor could be exploited without recompense at the whim of the lord. By the thirteenth century, the distinctions between villain and serf had disappeared. Surprisingly, the position of the villain did not degrade to that of serf, the position of the serf had instead improved to that of the villein.

The fiefs physically reflected their class structure. The landowner, his family, and his soldiers lived within the walls of the fortifications. The vassals lived on parcels of farmland outside the gates but could withdraw into the fortifications in times of attack. The further from the fortifications the location of one’s house, the lower one’s station. The bastion against attack for the furthest houses might not be a wall, but a hedge.

Daily Life

A singular significant advance of the Middle Ages was the large scale cultivation of the land and the domestication of animals. The control over the land, which meant the clearing of significant portions of it of woods, helped to eliminate food shortages throughout the year. It also meant that not all members of the society need be occupied in acquiring food. Hence in the origin of agrarian advances one finds the beginning of professional specialization within the society and the consequent beneficial rise in the society of the quality of goods, education, and organization.

Improvements of agrarian techniques and their application did not spell the end of earlier hunting and gathering activities. Not so much of the forest had been pushed back from civilization’s structures that wild animals did not flourish. Dangerous animals such as bears often wandered in search of food into cultivated areas and presented real danger. Hunting and gathering filled the table in lean times and supplemented not only the basic available foodstuffs, but offered a necessary variety in diet and hence nutrition. Without refrigeration but with new sources available, new methods of preparing and storing food developed. For example, wine became a means to hold perishable fruit, cheese permitted a longer life to cow’s milk, and bread became important as a way to convert inedible stored grain to digestible form. Spices became increasingly important and were often used to disguise rancid meat.

Hardships of environment were shared by the nobility and peasant alike. Manor houses were dark, dank, and drafty. Many of the health hazards of the peasant house, such as smoke from wood fires used to cook and to heat, were present in equal proportions in the best houses. The walls of peasant houses were constructed of wattle and daub (mud and straw). The thatched-straw roof had a hole in the middle to allow the smoke from the cooking and heating fire to escape and duly allowed in the rain and snow. The floors were dirt, the beds were fashioned from a box of straw, and the furniture was a table and several three-legged stools.

The peasant diet was limited and monotonous. He ate bread, porridge, and cheese year round. In the summer, the diet was augmented by vegetables from his garden. Further additions came from the berries and other fruits he was able to gather and from the game he was able to kill. Game meats were fresh, but those available in the open markets were often badly cured and half putrid. If crops were bad, he suffered, and death from starvation and disease were commonplace. Beer and wine were always available, and they doubtless, and this is not said flippantly, helped dull the pain of existence.

The peasant workday lasted from sunrise until after dark. Life was not regulated by the clock, since accurate time measurement did not evolve until later in the period, but by the daily cycle of the sun and the yearly cycle of the seasons. Once the animals were secured for the night, the peasant had his dinner and a few hours for himself.

Religion and the Peasant

Throughout the Middle Ages, the portrayal of Christ began to evolve in a way that made Him more accessible to the vassal. In the early Middle Ages and in concurrent Byzantine culture, emphasis had been placed upon the glorified, omnipotent, and distant Christ. Around the tenth century, the Passion began to move to the fore. The telling of the Passion and its depiction in art made Christ more accessible by making him more accessible and more human. No longer just a remote icon, He was seen in his human suffering and sacrifice, facts of life central to the vassal, and His reward for his virtue was driven home. The shift in conceptualization permitted the worshipper to empathetically embrace Him, and prompted enthusiastic lay participation in cathedral worship and cathedral building.

For the dispossessed elements of feudal society, the crofters, vagabonds, beggars, and the like, a class of people in a chronic state of uncertainty of survival, institutionalized religion was inadequate. For the class of people outside the mainstream, standard religious ideas became inadequate in the face of developments that threatened existence, namely any disturbing, frightening, or exciting event. New types of preachers, some drawn from clerical ranks and others from the laity, emerged to teach greatly expanded interpretations of a religion that already embraced mystery, sensuality, and superstition.

Excess was part of mainstream Catholicism, in action and symbolism. Self-flagellation was common practice during the plague. The gargoyle of Gothic architecture, terrible nightmare beasts that represented evil, adorned cathedral exteriors. Some were carved into the wall, at eye level, as warnings. Large gargoyle sculptures are always mounted to face outwards to symbolize the flight of evil from goodness. In mechanical function, they were often rainspouts.

Graphic and gruesome gargoyle warning to sinners

Gargoyle rainspout on Notre Dame Cathedral

Psychological Relief: High Holidays, Feast Days, Weddings, and Funerals

The Church often furnished the majority of bright spots in the life of the peasant. Sunday Mass offered a relief from the relentless routine and labor. Special occasions were truly special. The High Holidays of the Church, Christmas and Easter, were foremost among holidays and entailed feasts, splendor, and elevated ritual. By the late 1300s, the Church calendar embraced upward of fifty holidays, or roughly one per week, that involved the commemoration of the apostles, saints, and martyrs. Most welcome to the vassal, they meant the cessation of labor. In turn the vassal supported the central source of his worship, the cathedral church, with his endowments and gifts. Inns remained open, not so much to furnish drink, but rather to furnish meals for visitors.

Other occasions that permitted feasting and social intercourse were weddings and funerals. The wake was conducted considerably different than in our time, turning more often than not into crude and rowdy bacchanals called “ales” in

Chivalry

Manners and gentility did not evolve until relatively late in the Middle Ages. Prior to the emergence of a chivalric code, gluttony was among the most common of vices. The quantity of alcohol consumed was staggering by any standard. At dinner, everyone carved his bit of meat with his own dagger and transported it to his mouth in the fingers of his free hand. The dagger never left the right hand throughout the meal; it was needed in defense against assassination. The reality of dinner-time danger lingers today in two customs. The setting of cutlery on the modern table retains the position of the knife to the right, in easy reach of the hand in which most medieval diners held their weapon. Americans switch hands, grasping the fork in the right hand after they’ve cut their meat. Europeans do not switch, however. They transport the cut portion with the fork held in the left hand and retain, throughout the meal, the grip of the right hand on the knife.

Scraps were not pushed to the side of the plate and placed later into the garbage bin, they were thrown to the floor for the ever-present dogs to fight over. Women were regarded as marginal to existence. The basic fact set the rules: women were physically weaker than men. Hence women were treated, at best, with indifference and, at worst, with brutality and violence.

The emergence of the chivalric code in the twelfth and thirteen centuries brought with it significant improvements in social interaction. The code had its origins in the cult of Mary, the Virgin mother of Jesus, and came to represent the acme of social and moral behavior. Under this value system, the virtuous woman was equated with the Virgin and so warranted respect and protection. The idea never really entirely worked, and the balance of idealization and hormonal drive led to the double standard of behavior that is current today. Chivalry brought with some very fine standards. The ideal knight strove to be virtuous, loyal, brave, generous, truthful, dutiful, and reverent. He was required by code to be kind to the poor and defenseless, to disavow unfair advantage and sordid gain, and, of course, to give his life in defense of his nobleman. Chivalry elevated the status of women to high cult and elevated knighthood to an art form. The love poetry and love chansons of the late Medieval period attest to the new social organization and to the spread of education down the social ladder. Vestiges of chivalry are everywhere today, from the grace of opening a door for another to ideals of fair play in sport and war.

Guido d'Arezzo (d. after 1033) made significant contributions to practical music in his Micrologus (c1025-28). For one, his book contains the first description of a four-line musical staff that permitted accurate pitch notation.

He is also credited with a system of singer's training, known as solfege, which is employed today and which is known by the syllables do re mi. He developed the "Guidonian hand," the naming of the various joints of the hand after the notes. A choir director could use the hand to teach his choir new music quickly, efficiently, and accurately simply by pointing with the index finger of one hand at the appropriate joint of the other.

Another important contribution is his definitive identification of the eight Church Modes, the scales in use in contemporary music. There were four "authentic" and four "plagal" forms. In the authentic forms, the melody ascends from the tonic note and returns to it at the end. In the "hypo" or "plagal" forms, the melody descends from the same tonic note and ascends to it to end. In all, Guido gave eight modes.

Each authentic mode was assigned a name according to its starting note and the pattern of half and whole steps within the octave. The modes and their ranges are given below. [W=whole step, H=half-step]

Phrygian (E-F-G-A-B-C-D-E)

Lydian (F-G-A-B-C-D-E-F)

Mixolydian (G-A-B-C-D-E-F-G)

The Dorian is similar to the modern minor scale except that the sixth degree or note is raised. The Phrygian mode is also similar to the minor scale except the second degree is flatted. The Lydian mode resembles the modern major scale except that its fourth degree is raised. The Mixolydian is like a modern major scale with the seventh degree flatted.

A comparison of Guido's church modes to Ptolemy's tonoi reveals that they are the same scales and same names are used. In Guido's account, however, the names are assigned to different modes that in the tonoi. Ptolemy's Phrygian mode is Guido's Dorian, and so forth. The mismatch demonstrates the educational schism and disruption of the transfer of information from earlier to later times caused by the invasion of the hordes from the central steps of Asia, the ancestors of modern Europeans, and the subsequent fall of

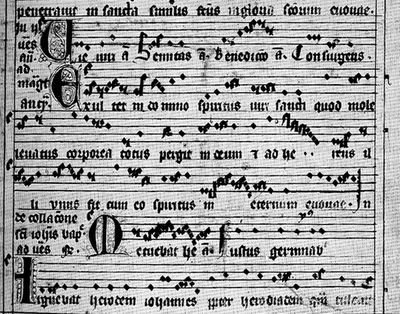

Church canon prohibited changing the notes of the chant that had been codified and standardized through the efforts of Pope Gregory II, Charlemagne, and others. Musically inclined clergy felt their creativity stifled and sought ways to make musical contributions to the liturgy without violating rules. One solution was the trope.

The practice of troping embodied the addition of music, text, or both between lines or at line ends of a chant.

The example that follows gives the textual additions but not the music. Moreover, the example is not an actual trope but nonetheless demonstrates form resulting from the trope process. Here additional material is added before and after the Psalm verse. As noted, chant was sung as a means to enhance texts drawn only from the Book of Psalms. The trope texts invariably furnished additional commentary on the meaniing of the Psalm or "set the stage" for the Psalm.

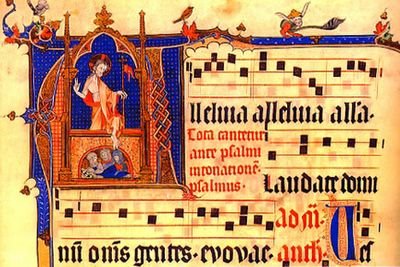

A study of the score reveals that the Psalm does not begin until the marker "Ps" in the fourth line. The Psalm itself is a well known-verse.

The Psalm verse (marked Ps in the score) follows:

Sing ye onto the Lord a new canticle, because he hath done wonderful things.

The ending is the Gloria Patri,:

"Glory be to the Father, Son and to the Holy Spirit."

The letters "E u o u a e" appear at the end of the score and do not form a word. Instead each letter is the first letter of each word of the standard closing formula of the musical portions of the Mass "as it in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end. Amen."

Tropes became more extensive with the passage of time. By the Middle Ages, the trope sections had spun off into a variety of new forms. One particular type of trope, the Alleluia jubilus exerted special influence. In the jubilus, a florid line of new music, or melisma, is sung to the last syllable "a" of the word alleluia.

The strict Church canons against changing chant melodies or text led to the addition of a second (and later third and fourth) line of music below or above the chant melody. The new process, called organum, had profound consequences on Western music, leading to the emergence of rules regulating combinations of simultaneously sounded pitches. These rules are today called harmony. The highly sophisticated system of harmony is a crowning achievement unique to Western music. Only with the global spread of Western influence in recent centuries did harmony become part of the music systems of other cultures.

Despite the inception and rise of polyphony in the ninth century, new monophonic chants continued to be composed. As noted, they were not included in the liturgy proper but used in ancillary worship. A principal composer of new chants as well as sequences was the charismatic Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179). She is the earliest composer to whom a specific body of musical works can be ascribed.

The Rise of Organum and the

The origin of organum is unknown, but the earliest records of it are found in manuscripts dating from the ninth century. Originally, organum was a type of improvised polyphony in which a second melody was fashioned above or below the melody of the chant. In its earliest form, the two voices moved note against note at the interval of a fourth or fifth.

Parallel organum

Within a short time, the musical texture began to evolve. Each note of the chant melody began to be held longer than its normal value in the original version. The protraction of the time values was described by the French verb tenir, to hold, and from the verb comes the name for the voice that sang the chant, tenor. Around the same time, the tenor was assigned to the lower voice and became known as the cantus firmus, literally “firm melody.” The improvised voice no longer sang note against note with the tenor, but instead featured melismatic passages. Since the improvised higher voice contained many more notes than the chant, care was taken that when notes of the two voices occurred at the same time, they would sing perfect consonances. This use of the chant as the musical basis became the primary compositional method, albeit with significant advances, throughout the period from the twelfth to early seventeenth centuries. Each voice sang the same liturgical text in Latin, though at different rates. The early form of this type of orgaum is called florid organum or Aquitane organum. It has become associated with the St. Martials monastery in Limoges in southwestrn France.The cantus firmus is found as the lower voice in the present example. The cantus firmus is already protracted in comparison to the upper voice. Note that there are now indications of the values of duration for any of the notes.

Aquitane, St. Martial, or florid organum

Two outstanding composers of organum, each working at Notre Dame cathedral in

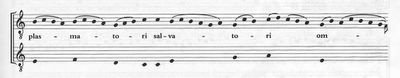

Chant and its use by Leonin as a cantus firmus

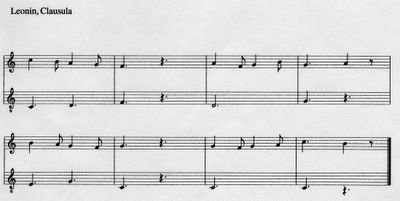

The second composer, Perotin (fl.1180-c1238), was known for his compositions in a newer type of organum, discant. Organum purum and discant differ in the treatment of rhythm. In organum purum, the singers had to take care only that the notes intended to be concurrent were sung at the same time. The slow-moving tenor permitted the quicker moving voice, the vox organalis, to unfold in rhythms not dissimilar to chant. In discant, the tempi of each voice still differed but the rhythm of each voice was closely regulated. To this end, composers borrowed several rhythms from poetry and applied them to music. The system of values was known as the rhythmic modes. Each value of each poetic voice was based in triple meter, that is, each lasted for the duration of three beats. The six rhythmic modes and their values follow. Long values, indicated by L, received two beats; short values, indicated by S received one. Triple longs values, indicated by T, received three beats. All are executed against a three count, or triple meter.

I. Trochee: L S

II. Iamb: S L

III. Dactyl: T S L

IV. Anapest: S L T

V. T T

VI. S S S

One can see a typical application of the rhythmic modes in the present example of discant by Leonin. The upper voice primarily follows the rhythm of the trochee. The lower voice, which contains the cantus firmus (melody of the chant), unfolds in the fifth mode. As noted, the application of the modes permitted easy alighment of the voices and imbued the music with a strong, dancelike, beat.

The rhythmic modes permitted the easy and accurate alignment in time of two or more voices and permitted the voices to move more quickly in relation to each other. Since all the modes are based in triple meter, different modes could be simultaneously used in different voices. Modes I and V were the most common and. in a two-voice texture that features these modes, the upper voice would express a L-S combination for every T in the cantus firmus below it.

Each section could be based in a different phrase of the cantus firmus. When the chant was exhausted, composers simply began the cantus firmus again or reused some portion of it. The upper voices of the purum and discant sections were newly composed, and each purum section and each discant section differed musically from earlier or later ones, even if the same phrase of the chant were used as the cantus firmus for more than one section. Composers, especially Perotin, began to compose substitute discants, that is, use the cantus firmus from an existing discant and compose new music for the upper voices. The new discant often substituted for the original one. The practice also prompted musicians and listeners alike to begin to regard the discant as an independent or free-standing composition.

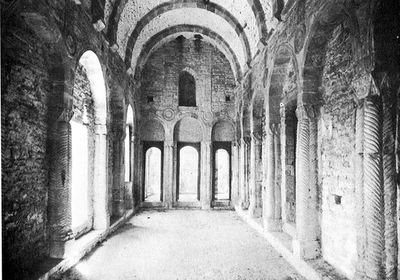

Cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris

Cathedral of Notre Dame, ParisSaturday, April 08, 2006

Medieval Christian Art: Vestiges of Earlier Times

Ancient Formal Elements

Several characteristics from ancient art are notable. In Egyptian bas relief, the artist did not portray the human figure naturalistically. Instead he depicted each part of the body from its most definitive view. Legs and arms were shown from the side view while the trunk was viewed from a full-frontal vantage point. No attempt was made to create a sense of depth of field, or illusion of "foreground-background" relationship. Here the artist worked from what he knew, not what he saw. The result was an idealized abstraction of human form, an icon whose parts reaffirmed and validated the Egyptian concept of the body. Other figures, such as birds, were similarly reduced, condensed, and abstracted. The Egyptian artist did not concern himself with relative proportions.

Portrait Panel of Hesy-ra, from Saqqara, c2650 B.C., example of Egyptian bas relief

The abstraction of form in Egyptian bas relief did not carry over into Greek or Roman painting or sculpture. The aim of the Greeks was clearly the visual celebration, not cerebration, of the beauty, power, and drama of the human body. Naturalistic rendering better suited their purpose. Whereas the Greeks portrayed gods and atheletes, the Romans built upon the Greek style by adding specific identities to their busts.

"Portrait of a Roman," dated c80 B.C.

The different needs for meaning of each society determined, of course, the nature of the realization. For the Egyptians, the figuration represented man on a fundamental level, a kind of self-validation of order. For the Greeks, the figuration offered a model of beauty and power. The embrace of beauty was far more than just sensual. The figuration conveyed visually the standard of physical conditioning to which each citizen should aspire, a physical prowess absolutely essential to survival in a world of city-states and empire-building. The Roman addition of the facial features of leaders aggrandized these leaders and helped to institutionalize them in a state larger than life.

The Market Gate from Miletus, example of Roman gate, c160 A.D.

European Christian Application: Changes in Symbollic Meaning

The significance of the arch as a portal is paramount to understanding its meaning in the Christian belief system. One enters the church, "God's house," through the portal of the arch. Inside the ceiling might consist of a tunnel created by extending arch in its depth. The altar itself is framed by another arch, and the portal created by this arch over the altar is the one that leads through true belief to the afterlife. On a side note, the most churches, then and now, have the cross as the footprint of their floor plans.

Santa Maria de Naranco, completed 848, exterior view

Santa Maria de Naranco, interior view

The two architectural examples presented here, one Carolingen, the other Gothic, are separated in time by three hundred years. Another architectural style, Ottonian, enjoyed currency in the intervening centuries. All three styles display the features described above, the arch of Roman might now imbued with the meaning of God's omnipotence and promise.

Chartres Cathedral

Between the time of the rule of Charlemagne in the ninth century and the high Gothic in the fourteenth, cathedrals grew dramatically in size and height. The cathedral played a special role in the religious and economic life of the Medieval community. The grand dimensions of the cathedral far exceeded any structure a layman could build. Once inside the front arched portal, the parishioner entered an "other-world." This "other-world" was filled with magnificent and expensive religious art, unusual light effects, sophisticated and ethereal music, "true" relics, and mysterious ritual. In brief, the rituals of belief inspired in the faithful a sense of spirituality, piety, and awe, and this emotional state was bolstered mightly by architecture on a scale so grand that it was difficult for the peasant layman to apprehend.

The cathedral could also add considerable monies to town coffers that relied primarily on aggrarian earnings. The cathedral became a source of revenue when it assumed significance as the destination point of religious pilgirmage. Size, aesthetics, music quality, and the quantity of sacred objects, such as relics, figured prominently in the success of the cathedral in attracting tourists.

The development of the flying buttress (see exterior view of Notre Dame in "Rise of Organum") permitted new architectural features. The buttresses absorded the load of the roof and diverted it outward, eliminating the need for the thick, heavy walls of earlier structures. Not only were thinner walls and considerably higher roofs made possible, but large areas of the wall could be replaced by stained-glass windows. The stained-glass windows profoundly improved the interior aesthetics. Earlier cathedrals had relatively lower ceilings. Their thick walls could safely accomodate only small windows. Inside, then, these structures were dark and gloomy. The high ceiling of the Gothic cathedral was itself a stunning achievement, and now the windows allowed multicolored light to set the vast interior space awash with light.

Chartres Cathedral, view of upper gallery windows

Moreover, the stained-glass windows fulfilled another critical function. The typical parishioner was illiterate. The windows were used to educate, and the scenes portrayed in the window designs were intentionally drawn from the Bible. The window designs themselves incorporated hundreds of shards of geometrically-shaped glass joined together at the ends by strips of lead. Similarly, the scenes were filled with abstract figures, recognizable in their identities by their activity, but not developed, as in ancient Greek or later Renaissance, Baroque and Romantic art, for their realism or beauty of human form. In a final but dangerous point, at least for this author, is the casual and unresearched suggestion that the halo and the Roman arch are not so disimilar.

Chartres Cathedral, detail depicting the "Death of the Virgin"

Not surprisingly, the arch and abstracted figuration found in Medieval architecture and stained-glass windows are also the prinicipal components in the art that adorned religious manuscripts of the period. All material items were made by hand. Books were copied by hand by monks in the monasteries for use in-house or by the literate members of the ruling families. Religious messages supplemental to the text could be conveyed in a variety of ways that also greatly enhanced the beauty and value of a manuscript. One common means, manuscript illumination, was the pictorial decoration of the first letter of the first word on a page. Another means involved scenes on the covers. Bookcovers were often carved from ivory or made from precious metals and studded with gemstones. The eqaution of power and wealth is a very old one.

The examples that follow span four hundred years, yet they all share common characteristics. One would expect to see some change in the artwork over so long a period of time. Indeed, if one visually ordered the examples on the basis of "evolution," the "Vespasian Psalter," the crudest realiztion of the set, would be placed first and the "Lorsch Gospels," the most naturalistic rendering, would be placed last. Different artisans in different regions worked to their own sensibilities, guided foremost by the tenet that the image must express a meaning that teaches, reminds, or reaffirms.

The Medieval world, then, was one ruled by symbols. Symbols pervaded every aspect of life and assumed a critical role. To moderns, the orientation toward symbology reveals a fundamental aspect of Medieval man's view of life. He lived outside the suffering of his everyday reality. He would be relieved in the afterlife and, in the meantime, he could glimpse the world to come in the intellectual, intermediate world created by the icons and signs that surrounded him.

As noted, the following manuscript illuminations have common elements. All of the examples are narrative in nature. The arch appears in some form in each example. There is no development of spatial relation within the field, that is, there is no effort to create the effect of "foreground-background." Although differing degrees of realism are found among the renderings of human form, all of them are essentially abstract. The characters are recognized by the scenes in which they are immersed or by ancilary features such as objects that a figure might hold. The open book, for example, was the symbol for the teacher. The degree of abstraction is apparent, even in the more naturalistic figuration of the Lorsch Gospels, in that the folds of the clothing define the body, not vice-versa. As in Egyptian art, scale is not important.

Gospel of St. Matthew, manuscript illumination

Lorsch Book Cover, Ivory, c810 (Museo Sacro, Vatican, Rome)

Vespasian Psalter (British Museum Cotton MS Vespian A, England, Canterbury, c800). David, Traditional Author of the Psalms with his Musicians

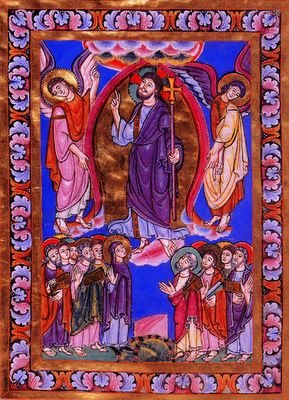

Gospel Lectionary (British Museum Egerton MS 809, Swabia, possibly Hirsau, c1100). The Ascension

Salvin Hours (British Museum Add. MS 48985, England Lincoln, possibly Oxford, c1270). Christ Before Pilate

The "Madonna in Majesty" is a painting. The gold paint contains real gold. Here the arch is abstracted into a point (review the interior view of Chartres Cathedral, above), but the flat field and abstracted figuration of earlier manuscript illuminations are still intentionally present.

Cimabue, Madonna in Majesty (Louvre, Paris; executed originally c1295-1300 for Church of St. Francis, Pisa, taken to France by Napoleon as spoils of war)

The Arch in Later Times

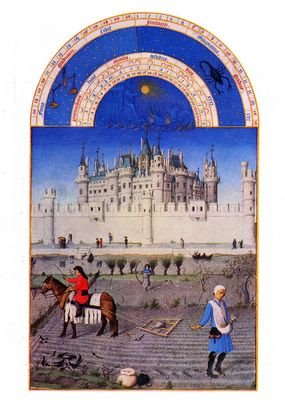

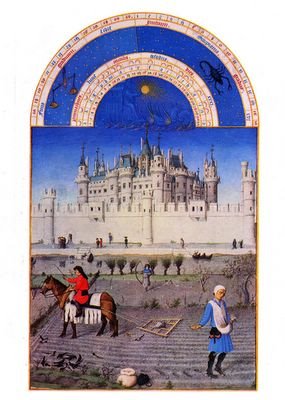

The subsequent examples date from the late Middle Ages and reflect the discoveries of perspective of Giotto (see Kamien). Curiously, the mathematics (geometry) that made the realization of perspective in art possible had been in place since the second century. "October" hints at the radical shift in art and society that Humanism (see "Humanism" in Renaissance Lectures) would shortly bring.

First, there is the perspective. The figures, though not well-developed by Renaissance standards (the clothing defines the body), make meaningful strides forward in gestures that are representative but also possess elements of realistic depiction. The figure on the right is sowing seeds for a winter crop, and the viewer can almost see the motion of his arm. Unlike the earlier images, this sower is not static.

Like the paintings to follow, however, the gesture conveys an activity of grace and refinement, not one of hot, tiring, dirty labor. The world in which this activity unfolds is one of tranquillity and purity, a significant shift in social attitudes since this world of tranquillity is earthly. Moreover, the Roman arch, by this time more a Christian symbol than an Imperial one, is interpreted in terms of the Zodiac. This arch, then, is not a portal to the Christian afterlife, but one to some small patch of peace, well-being, and relief on earth.

Limbourg Brothers. "October" from Les Tres riches <>heures du Duc de Berry, (1413-16)

"Madonna with Child and Saints" offers a curious study. First, the painting features perspective, but its execution is not convincing. The viewer sees three distinct fields instead of a graduated foreshortening that geometrically recedes into the horizon. The saints occupy the first plane, and the Madonna and Child define a second. personal plane not shared by any other figuration. The Roman arch, present in its most classic reiteration, is actually the agent of perspective.

Each of the figures holds a gesture, but only the second figure from the left expresses a "body language" that is dynamic or believable. The eye is drean to this figure instead of to the Madonna and Child, the supposed central figure. In part, the veiwer's eye is drawn to him because he wears fewer clothes than the other figures but, more importantly, because the his posture displays a natural relaxation and an element of motion.

Domenico Veneziano, Madonna and Child with Saints, c1445, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

The final examples date from the reign of Louis XIV, the "Sun King," of

Under Napoleon, classical formalism would continue to be nourished. The ancient symbols would transfer to him as Emperor. Indeed, he would fill

Versailles, late seventeenth century, interior view of chapel

"Salon d'or" in the Paris house of Comte de Toulouse, late seventeenth century (now Banque de France)