Romanticism in Art

Three types of content became manifest in painting, beginning in the Roccoco and extending into the middle of the nineteenth century, reflected the intellectual and political upheavals sparked by the Enlightenment, itself the philosphical offshoot of the Scientific Revolution.

In the Roccoco, an isolation of the wealthy, aristocratic class from the lower class is evident in the art created for the consumption of the former. It is characterized by an "otherworldly" quality, a fantasy world portraying not only the physical trappings of the aristocracy, but also reflecting a creeping decadence in the often sensual character. The focus upon the tangible and the covertly erotic stands almost as a denial of events threatening from the real world.

The paintings of Antoine Watteau record a shift in style and in French Society. After the death of Lousi XIV, many members of the aristocracy moved back to Paris from Versailles and environs. The city houses did not permit extensive decorative development to the exteriors. New, smaller accomodations required decorative art to be reduced in its scale and to be intended for indoor display. Emphasis was placed upon intimacy, elegance, and delicacy.

Like most of his paintings, "A Pilgimmage to Cythara," the isle of love, portrays the aristocracy in a park-like setting. The link to the love of the beauty of nature would remain as a component of later Romantic thought. Dramatic depth comes in the moment of sadness that fleets across the otherwise happy scene--it is the moment of departure. Also inherent in the painting is the interweaving of real life, fantasy, and theatre. The elements combine to create both an ephemeral heaven on earth, rather than in the afterlife. The style also conveys a special world of elegance, grace, privilege, and beauty that exists in the collective aristocratic imagination and that does not admit any of the ugliness of life, including the poor.

Antoine Watteau, "A Pilgimmage to Cythara" (1717)

Jean-Honore Fragonard's paintings bespeak a sensuality and playfulness characteristic of aristocratic decorative art. Like Watteau's "Pilgimmage," Fragonard develops his atmospheric effects. Unlike Watteau's work, the atmosphere of "The Bathers" breathes a delicious sensual abandon. Fragonard's work fell from favor as the Revolution approached.

Jean-Honore Fragonard, "The Bathers" (c1765)

Thomas Gainsborough made his living as the premier portrait painter of English society. Not surprising to learn after viewing "Robert Andrew and His Wife," Gainsborough began as a landscape painter. His scene contains a certain charm to modern eyes and differs significantly compared to the previous French examples.

The reasons for the differences among the works lies in the entanglement of politics and religion. The English temperament of the time was profoundly formed by the violent end of their monarchy and the prevalant religious climate of Puritanism. Nonetheless, the scene is one of quiet wealth and security and, like the French paintings, is tied to the beauty and bounty of nature. Although Gainesborough does not depict an orgy of warm or sensual emotion, the immense well-being of the couple, seated in their perfect, beautiful world, cannot be missed.

Thomas Gainsborough, "Robert Andrews and His Wife" (1748-50)

Revolutionary images, or at least images that dramatically championed the rights of man or condemned injustices against him, began to appear in France around the time of the Revolution and continued to be produced into the mid-nineteenth century. They were intended to inflame spirits. Many of the paintings were inspired by actual events.

Eugene Delacroix chose the female figure as the ideal embodiment of freedom, liberty, decency, and human rights in two important paintings. In one of these paintings, "Liberty Leading the People (1830)" (see Supplemental Lectures icon), the female is the symbol of hope and inspriation. In the second, "Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi," she is soon to be a maytr. Delacroix had great sympathy for the Greeks in their war with the Turks, and one of his earliest important works depicts a Greek family waiting in Turkish capitivity to be starved to death or executed outright.

Eugene Delacroix, "Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi" (1826)

Other painters depicted atrocities committed by government or the private sector against humanity, invariably protrayed as the peasantry or as members of a defenseless working class. Francisco Goya's "The Third of May, 1808," recorded the wholesale slaughter of villagers by Napeoleon's troops, dashing Spanish hopes that the French would bring social reform.

Francisco Goya, "The Third of May, 1808" (1814-15)

Theodore Gericault chose to marry the busy Renaissance-Baroque group scene, with its careful, classical, and dramatic rendering of muscular and beautiful human forms, with content of unimaginable horror. The survivors of the shipwreck of the French government ship Medusa, afloat on a makeship raft, were allegedly forced to resort to cannibalism. Gericault heightens the impact of the scene by capturing the instant the seaman make contact with the rescue ship, the Argus.

His studies of anatomy and its dramatic posibilities, in both Renaissance and Baroque art and in the morgue, allowed him to imbue the painting with immeasurable force. There are many levels of meaning here. Each person tells his story but, taken as a whole, a primary theme is the heroism of man against the elements and his triumph over it.

On a darker note, the hunger that drove men to desperate measures will almost instantly be replaced by shame and self-loathing once aboard the Argus. A greater culprit, however, in bringing the sailors to this test is the corporate ship-owner, the monarchy restored after Napoleon.

Theodore Gericault, "The Raft of the Medusa" (1818-19)

The art of French painters such as Delacroix, Gericault, Jean-Auguste Ingres, and many of their contemporaries contain strong calssical elements and so seem to link, at least formally, this art to an earlier age. Postures and body details echo those of ancient Greek Hellenist statuary or the dramatic scenes depicted in Renaissance and Baroque art. Gericault" "raft" uses the well-proven Baroque pyramid structure to organize the figures.

French Romanticism had to overcome special circumstances not found elsewhere in Europe. For one, the tradition of "classical formalism" in the seventeenth century had been central at the court of Louis XIV, where the art, architecture, and music strongly imitated classical forms. All three media were marked by certain traits that included decorative function, strong affectation, artificiality, subordination of content to form, and mechanization.

This classical formalism continued into the nineteenth century with the rise of Napoleon. In his evocation of the power (and legitimacy) of the ancients, Napoleon adopted ancient symbols and the ancient names for various offices including “emperor.” Moreover, he desired that Paris reflect ancient power and glory and, to that end, set about filling Paris with buildings modeled after classical ones. Not unexpectedly, the academy and classical painting simply continued under Napoleon.

After Napoleon’s final exile, French painters did not return to the style of the Revolution or that of the years of his rule. Instead Delacroix and Gericault distorted the classical formal tenets with intense, lurid scenes glorifying the struggle for freedom, social injustice, or dramatic moments from Medieval history or myth.

Jacques-Louis David served as the official painter to Napolean. The neo-classic style in which he painted was considered by 1800 to adhere too rigidly to classical tenets, though this fact would have been a reason for Napoleon to embrace him. Although considered revolutionary at the end of the eighteenth century, the neo-classic style may be regarded as yet another manifestation of the long-standing classic traditions of the French court. David's application of the style was, however, revolutionary, and he used his art work as a means to participate in the Revolution. He survived both Robespierre and imprisonment. After his release, he became an enthusiastic Bonapartist, ultimately painting important works for Napoleon.

Jacques-Louis David, "Portrait of Madame Recamier" (1800)

Later painters such as Jean-Auguste Ingres, retained the classical formalism but slipped into mannerist renderings. In Ingres "Odalisque," the pose, subject matter, and formal aspects are clearly classical and reminiscent of David's protrait, yet the dimensions of the figure are not correct. The upper and lower portions of the figure, dividing at the bottom of the rib cage, are not in the same scale!

Jean-Auguste Ingres, "Odalisque" (1814)

Other elements also shape French art after Napoleon. A strong social undercurrent, a hunger for the exotic, is evident in some paintings by Delacroix and in the paintings of his contmeporary, Ingres. The fascination for the new and unusual became established as a trend that would play a significant part in art and art music in the second half of the nineteenth century.

This interest in the exotic was fueled to a significant degree by the artifacts brought back to Europe by early archeological expeditions to Egypt and the Near East. A second point to remember is that French colonial holdings were largely in Africa and portions of the the Near East. Both Delacroix and Ingres painted exotice subjects. Delacroix's interest in the Orient surfaced in his paintings depicting the matyrdoom of Greece. Delacroix was not very complimentary to the environment that sparked the painting. He wrote in a letter that "here fame is a word without meaning: everything turns to a sweet laziness and it cannot be said that this is not the most desirable condition in the world."

Eugene Delacroix, "The Women of Algiers" (1834)

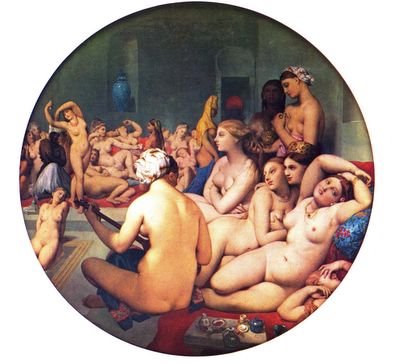

Ingres' painting, "The Turkish Bath," was conceived in a similar vein. Ingres was Delacroix's rival throughout their careerss, and both painters had some fascination for exotic, here Muslim African, scenes and customs. The "Turkish Bath" was finished late in Ingres' life. Work on it spanned nearly thirty-five years, and he considered it his consummate masterpiece. It was originally intended for Prince Napoleon, but his wife considered it too immoral and blocked its purchase.

Jean-Auguste Ingres, "The Turkish Bath" (1863)

A Later Break with the Academy: Realism

Little did Gustave Courbet (1819-77) know that his straightforward, pragmatic, and eminently practical assessment of contemporary art would result in an upheaval that would pave the way for new styles. To Courbet, the Romantic style of painting obscured the realities of his time. Romantic painting reflected the revolutionary spirit as it tranferred to the rights of man. Its emphasis on excessively emotive content, especially human triumph in the face of adversity, its imaginative but contrived exotic scenes, and its academic neo-Baroque and neoclassical ordering were simply out of step. He said, "I cannot paint an angel because I have never seen one."

Courbet chose instead to paint from direct experience. Although described today as "realism," his style and approach could more accurately be described as "naturalism." Courbet's scenes did not lack heroism or pathos, indeed his style still showed clear links to the underlying philosophy of Romanticism, but instead he portrayed, without grandiose inflation, the heroism of everyman. In "The Stonebreakers," it slowly dawns on the viewer that both workers are unsuited to punishing labor of this sort: the boy is too young, the man is too old. The figures are sympathetic, yet they to not appeal to the viewer for symapthy. In one stroke, Courbet captures not the grandiose gesture of the superhuman, but the quiet heroism of the common man.

Gustave Courbet, "The Stone Breakers" (1849)

Francois Millet (1814-75) worked along similar lines without attaining the same honesty. Both painters shared rural backgrounds, and Millet settled in the village of Barbizon near Paris to concentrate upon painting landscapres and rural scenes. Millet's assessment of the worker is more stylized and hence more in line with the Romantic tradition. "The Gleaners" captures the nature of the work and the relationship of man to the earth. The softened atmosphere, idealized renderings of the workers, and their careful composition do not convey the true hardship and places the painting in the Romantic school. Millet portrays the "hero of the soil" without conveying his reality.

Francois Millet, "The Gleaners" (1848)

The work methods of Camille Corot (1796-1875) differed sigmificantly from his contemporaries. Corot worked quickly, producing his canvases on site within a few hours of work. He sought to capture the "truth of the moment," although his instinct for architectural clarity, evident in all his works, bespeaks the stylistic influence of Poussin and other neoclassic representatives. The Romantic spirit is also evident in imaginative and idealized rendering of the landscape, especially in the conveyance of "freshness," harmony of man and nature, and immense well-being. In brief, the landscape of the Romantic painter is turned to a different meaning. As in Courbet and Millet, the supernatural, heroic figures in mortal strife are supplanted by less grandisose but a no less extraordinary subject, the ordinary man glimpsed in the context of a moment of his life.

<< Home