Beethoven as the Bridge to Romanticism in Music

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was, however, a composer of a highly passionate disposition. Although Beethoven had severe shortcomings in his social skills, he fervently believed in mankind. His thought informed by the Enlightenment and inflamed by contemporary revolutionary events, he sought to embrace and enlist other men in the promise of human fulfillment that these events seemed to offer. He was an early supporter of Napoleon, but was disaffected and alienated when Napoleon sought to have himself crowned Emperor. Beethoven was so appalled by Napoleon’s bid for absolute power, that he tore the original title of his third symphony, “Napoleon,” from the first page and renamed the work “Eroica,” or “Heroic.”

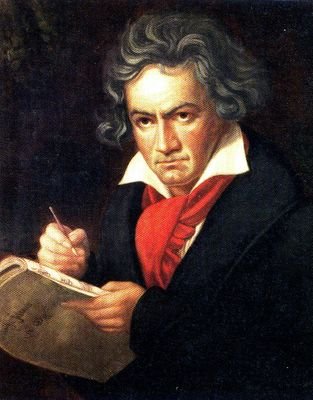

Ludwig van Beethoven

Despite his disillusionment, Beethoven did not digress from his convictions regarding the dignity, potential freedom, and rights of man. The seeds of German Romantic idealism, as noted a more powerful and cohesive train of thought than in other regions of Europe, were taking shape around him as he came to artistic maturity. Beethoven’s familiarity with the writings and convictions of Schiller and Goethe were evident; Beethoven used a text by Schiller in the choral last movement of his most overt symphonic and romantic achievement, Symphony No.9 in D Minor.

Beethoven regarded himself as a classicist, yet in his music he enriched the elements of the classical tradition with his urgent idealism. Beethoven imbued the music with the passion of Romantic idealism by the use of sharp and dramatic contrast. These contrasts pervade nearly all aspects of his mature music including the character of themes within a work, dynamics, key areas, tempi, orchestral color, and even meter. Beethoven’s classicism is also evident in his work method. He sought that every musical component should be in balance and have meaning. He worked slowly and carefully, and labored over the development of themes, the ways in which they could be developed, and even their suitability for development, comes to the modern scholar in his work books.

Despite the almost violent contrasts and character of the late string quartets, written after his deafness became total and around the same time as the ninth symphony, the classicist is nonetheless evident in the working-out of the motivic materials. The late string quartets and piano music were among Beethoven’s most significant, radical, and progressive works. They were not appreciated or embraced for at least thirty years after his death. When confronted by a critic who did not like or understand one of the late string quartets, Beethoven responded to the critic that it was not important since the music was ‘not for you.’

Beyond his immeasurable importance as a composer, Beethoven was also the first composer to be financially independent, that is, to support himself by the sale and performance of his music. As such, he was the first to break with the long tradition of church or royal sponsorship. His works were recognized at first hearing for their importance, power, and beauty. The symphonic works were absorbed directly and immediately into the orchestral repertory, where they have remained in popular usage to this day. The circumstance of immediate acceptance across the spectrum of listener, from the common man to the connoisseur, permitted Beethoven to reach and inflame a broad audience with his passionate ideals and to set the stage for the Romantic composers who would follow.

<< Home