The Principal Composers of the French Clavecin School

Chambonnières' family name was Champion yet he took his grandfather's title, which he seems to have used unchallenged. Chambonnières' reputation as a harpsichordist flourished in the early 1630s and by 1632 he had already filled his father's post as chamber musician to Louis XIII. His playing was praised in the writings of Pere Marin Mersenne (Harmonie universelle, 1635-6), who described him as "without peer." As part of his efforts to insure employment and social rank, Chambonnières also cultivated his skills as a dancer, appearing before Louis XIII and dancing later with Louis XIV and Jean-Baptiste Lully.

In the 1650s, Chambonnières met the Couperin brothers Louis, Charles, and François (not François Couperin, “le grand,” who was a nephew of Louis, the most prominent figure in the last generation of clavecin composers, and an important figure in the transition to the classic style). Chambonnières recognized their talents and helped to establish them in

In 1657, Chambonnières suffered serious economic setbacks including the appointment of Etiene Richard as the royal harpsichord teacher and expensive litigation against his property by his estranged wife (with whom he continued to live until his death) and others. A plot to replace him at court with Louis Couperin ran aground when Couperin refused to participate. The king was so impressed by Couperin's loyalty that a new post was created for him, although as a violist. A letter dated 1662 by Huygens mentions the influence of the 'low and evil clique,' likely a reference to the new appointment (1661) of Jean-Baptiste Lully as Superintendent de la musique de la chambre, as responsible for the low salary paid Chambonnières at the French court. A few months later Chambonnières' brother Nicolas died and, in economic desperation, Chambonnières sold the post held by Nicolas to Jean-Henri d'Anglebert.

That Chambonnières' retirement and Lully's appointment had more than a coincidental relationship is found in a comment of violist Jean Rousseau, uncovered by Francois Lesure. Rousseau states that Chambonnières could or would not accompany from figured bass. Chambonnières spent most of his life cultivating his solo style of playing. The adaptation to accompaniment from figured bass would have meant the forfeiture of that solo style and his roles as harpsichord master and aristocratic connoiseur to sit as an anonymous member in Lully's orchestra. Most of Chambonnières' music was composed in the 1630s and 1640s, but he did not publish it until 1670 (Pieces de clavessin, Livre premier).

For most of his life, Chambonnières posed as a connoisseur of the arts and aspired to the aristocracy. Chambonnières' pretensions were often underscored by his poverty, and stories about this poverty circulated around

Louis Couperin (c.1626-1661). Louis Couperin and his nephew Francois ("le grand") are the best known members of a large family of musicians. Louis Couperin is best known for his compositions for keyboard, including both the harpsichord and the organ. Little is known about Couperin's early years, but his association with Chambonnières and his talent led to immediate success in the Parisian musical world early in 1651. He served as the organist to St. Gervais from 1653, and around this time, he was offered and refused Chambonnières ' post. Louis Couperin is known to have played in at least four royal ballets but, more importantly, his musical activities allowed extensive contact with many of the most important musicians of his day. Among these was Froberger.

Couperin's output of clavecin music includes the basic suite movements; the prelude non mesuré, for which he developed the initial notation; and chaconnes and passacailles. Couperin is the first to recognise the affective potential of these forms. Of the twelve chaconnes, nine are rondeaux, establishing a link between these two forms. Couperin's music is more detailed and complex than that of Chambonnières, and the melodies and textures are more akin to contemporary lute music. Couperin never published his music, but it is preserved in the Bauyn and Parville Manuscripts. The numbering of Couperin's suites in this anthology follows that of Alan Curtis.

Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687). Lully was born in

Lully was a dancer and a violinist, but his first instrument was the guitar. He arrived in

As composer, Lully spent the first ten years of service heavily involved in the production of ballets de cour. This period was essentially devoted to the differentiation of national styles and the absorption of French elements, such as the dotted rhythm, into his music. A guitar element that remained in his music was the chaconne. Louis Couperin would be one of the most important developers of the chaconne for the keyboard; Lully, for the orchestral medium.

Nicolas-Antoine Lebêgue (1631-1702). Lebêgue was, like Louis and François Couperin and Jean-Henri d'Anglebert, an organist as well as a harpsichordist. Like Rameau and Louis Couperin, he was not native to

His clavecin suites follow the basic scheme of dances established by the lutenists and found in the music of Chambonnières and Couperin, but he also included many of the optional dances promoted by Lully. These dances were often repeated with doubles. Lebêgue was an innovator in the notation of the prelude non mesure, using differing note values to indicate important melodic segments. Lebegue began each suite in his first book, Les pièces de clavecin (1677), with a prelude, but wholly abandonned the practice by the time of his Second livre de clavecin (1687). Although clearly indebted to the music of Chambonnières and Couperin, Lebêgue 's harpsichord music is far less warm and intimate. It does display, however, the same sophistication as the music of d’Anglebert, his contemporary.

Jean-Henri d'Anglebert (1635-1691). D’Anglebert, who was both clavecinist and organist, was also possibly a student of Chambonnières. His earliest post was as an organist, but in 1662 he purchased the post of Ordinaire de la chambre du

The primary source of d'Anglebert's clavecin music is the Pieces de clavecin...diverse chaconnes, ouvertures, et autres airs de Monsieur Lully...quelques fugues pour l'orgue et les principes d'accompagnement (

Jean-Henri D'Anglebert

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764). Rameau was the most important French composers of dramatic music in the eighteenth century and a principal figure in the codification of harmonic theory. Rameau's total output includes clavecin pieces; stage works such as the opera-ballet, the tragedie-lyrique, and the comedie-ballet; and sacred cantatas.

Rameau received his only musical instruction from his father, who was the organist at

The Traité de l'harmonie, Noveau systeme de musique theoretique (1726), and several articles established Rameau as a theorist in

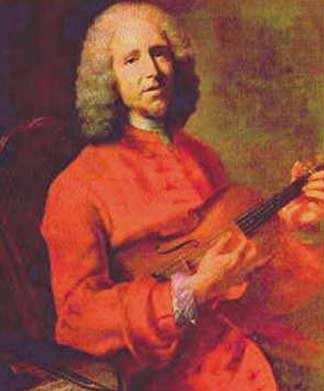

Jean-Philippe Rameau

Not all members of the Parisian musical intellegentsia, however, accepted Rameau's stage music, finding it forced, mechanical, difficult, and unnatural. Moreover they regarded it as subversive of the French opera tradition established by Lully. Rameau flourished nonetheless and later would see many of the same detractors defend his music, alongside that of Lully, in a later debate in the 1750s, la guerre des bouffons.

As a theorist, Rameau was a Cartesian who sought to establish his principles of harmony in the laws of the newly emerging science of acoustics. The core of his harmonic theories is based upon the results of studies by Pere Marin Mersenne and particularly of Joseph Sauveur (Memoires de 1701, presented to the Académie des Sciences) in which the primary consonants (the octave, fifth, and major third) were proven to be the strongest overtones produced by a vibrating body.

Rameau was among the first to recognize the identity of a chord regardless of its inversion and the significance of root motion in harmonic progression. His recognition and description of chord function serve as the foundations of modern functional harmony. His chord labels tonic, dominant, and subdominant are still in use today. His writings and music precipitated the perception that musical content in counterpoint and thoroughbass is determined by harmonic superstructure and governed by the rules of harmonic progression. His writings exerted a critical influence upon the development of several national schools in music theory into the nineteenth century in

Rameau published sixty-five keyboard pieces in four books (the last dates from 1741). The first three books antedate his dramatic stage works. Although Rameau's clavecin music contains elements of linear writing and is hence reminiscent of the keyboard music of Françcois Couperin (le Grand), many other elements may be traced to the earlier lute and clavecin models. Many of the clavecin pieces, particularly in the first two collections, are almost lute-like in their scope, texture, figuration, and tessiturae.

The contents of the first book comprise a suite, and the pieces of the second are dances or character pieces grouped by key but not organized in suites. Despite the small scale of these dance movements, they reflect nevertheless Rameau's power and depth as a composer and the successful application of his harmonic theories.

François Couperin (1668-1733, “le grand"). François Couperin was the son of Louis Couperin's brother Charles and the namesake and godchild of Louis' other brother, Francois (“le jeune"). No compositions are ascribed to François “le jeune," but he had a reputation for a willingness to extend a music lesson as long as the carafe were refilled. Couperin “le grand" composed for a variety of media including organ, harpsichord, chamber orchestra, and voice. His harpsichord music represents the late French classical school.

His early career was as an organist, and his only organ compositions date from 1690. Around this time, he likely stood in at the clavecin for d'Anglebert, whose failing eyesight often made the fulfillment of duty difficult. It was as organist, however, that Couperin first attracted employment at the court of Louis XIV, where in 1693 he took his place among the other court organists and Chambonnières associates, Nivers, Lebegue, and Buterne. This post opened other possibilities of employment to him, notably as clavecin teacher to members of the nobility.

From 1700 his activities became more diversified and included secular performances at

Francois Couperin

By the first decade of the eighteenth century the publication of books of harpsichord music dramatically increased, and the music in these books gathered the newer dances of French keyboard music into a characteristic suite format centered around the older obligatory dances. These suites usually contained no more than ten movements, but this number represented an increase in size over the suites of the early school. This expansion was anticipated in the music of d'Anglebert. In Francois Couperin's first collection, however, the average number of movements per suite was fifteen and, in the second, he included no fewer than twenty-three. A new descriptive term also appeared with this collection, the ordre. Although his second publication shows sensitivity to maintaining a single mood throughout each ordre, there is a clear movement away from the traditional suite. Nuclear dances were often omitted. Couperin instead included many of the optional dances brought into the suite by Lully as well as character pieces not linked by title to a specific dance but still maintaining a general dance character. Often these character pieces bore whimsical titles such as “Les matelots provençales” (“the provincial sailors”). An important feature of Couperin’s orders is that he did always adhere in his movements to a single key. His collections do not include any preludes non mesuré.

Couperin preferred three different structural types in his clavecin music: the binary dance, the chaconne, and the rondeau. As in the music of Chambonnières and his uncle, Louis Couperin, he often combined rondeau form with the chaconne. François Couperin’s binary pieces highlight the differences between French practices and those of contemporary German and Italian composers. In French music, the first sections were often substantially shorter than the second and the initial measures of the sections are not related motivically. Frequently the second section features new materials instead (see la Tenebreuse). In the binary character pieces, Couperin sometimes melded two binary dances into a single, larger movement. He often used different meters, different tempi, and even different keys, the most frequent relationship being a juxtaposition of minor and relative major, to create contrast within two conjoined binary movements

<< Home