Astronomy and the Church: the Scientific Revolution and a New Concept of God

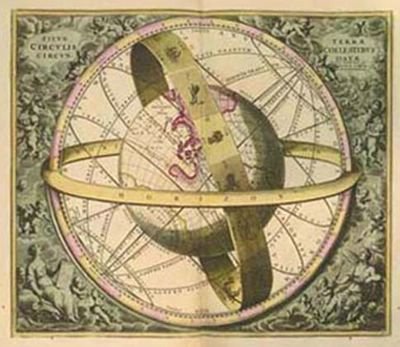

Strides in astronomy helped to revolutionize man's concept of the universe, his concept of God, and validated once and for all the empirical approach advocated by the humanists. One central scientific issue of the sixteenth century was the ordering of the solar system. The view purported by Ptolemy in his Almagest (150 A.D.) and revered as both Church and scientific doctrine described a universe in which the sun, moon, and planets revolved around the earth. Concentric crystalline spheres that surrounded the earth supported the celestial bodies. The planets moved as the spheres rotated. Beyond the spheres lay the realm of God and the angels. Aristotelian physics justified Ptolemy's universe, and the construct stood unchallenged until the sixteenth century.

Andreas Cellarius (c1596-1665), "Location of Earth with Celestial Circles" (1661)

The Astronomers

Difficulties with Ptolemy's system had been recognized for a considerable time before Copernicus (1473-1543) published his De Revolutionibus Orbitum Coelestium (1543). His assessment of contemporary astronomy did not differ from that of Ptolemy except for a single point: if the sun were the center around which the planets orbited, the mathematical problems and inconsistencies present in the Ptolemic system were essentially resolved. An important tenet of humanism that Copernicus stressed and that later became a basic component of scientific method was that no process, in his case mathematics, could be applied without empirical data and observation.

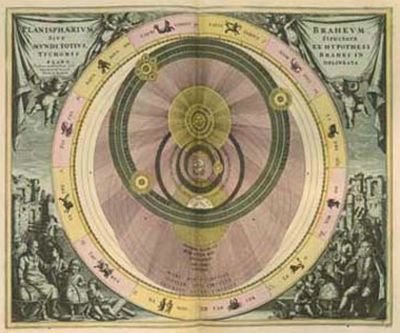

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), a scientific amateur, was able to furnish the next evidence for a sun-centered universe. He did not agree wholly with the Copernican view, but his objections gave Copernicus's ideas wider circulation. His contribution was in a form that Copernicus advocated, the collection of empirical data. Although he was not able derive mathematically verifiable theories of the order of the universe, Brahe's naked-eye observations of the celestial motion were the most accurate and comprehensive tables to be generated in centuries.

Andreas Cellarius (c1596-1665), "Brahe's Planisphere" (1661)

<>

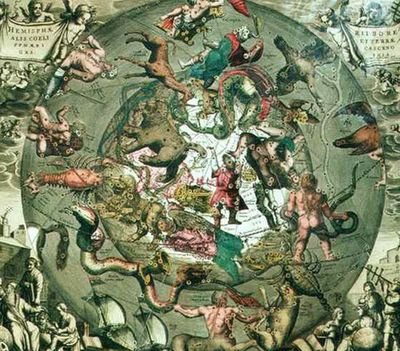

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), the son of Florentine Camerata member Vincenzo Galilei, increased the body of empirical data by the use of a new device, the telescope. He discovered stars where none had been known to exist, spots on the sun, craters on the moon, and moons orbiting Jupiter. His revelations did not prove the Copernican view, but they did disprove that of Ptolemy. Furthermore, the discovery that the universe was vast beyond comprehension unnerved many contemporary scientists and churchmen. His book Dialogues on the Two Chief Systems of the World (1632) earned him the wrath of the Catholic Church, and he was forced to recant his findings.

Andreas Cellarius (c1596-1665), "Northern Stellar

Hemisphere of Antiquity" (1661

<>

Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) resolved the thorny problems of planetary motion presented by the Copernicans, in particular that of elliptical orbits. In addition, he established a basis for physics that remained viable until the twentieth century.

<< Home