The British Invasion

British musicians also listened to music most Americans ignored—the music being made by African Americans. The British Invasion, then, came in two flavors: music with a decidedly British accent (and origin) and reinterpretations of American music. Groups such as Led Zeppelin and musicians such as Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton helped to spark new directions in rock but also helped America to rediscover its own musical culture. A casual listening to Jeff Beck’s Truth or Led Zeppelin’s first album bespeaks the Blues, not even disguised, just slowed and with the volume turned up to ear-shattering levels.

The Beatles' Second Album Cover of "Yesterday and Today." The first cover, which showed the boys holding meat cleavers and cruel grins as they stood over behead dolls, was pulled by the censors shortly after its release.

The Beatles: From Ditties to Musical Theater Concepts on Vinyl

The early music of the Beatles reflected British roots, with many of the songs using harmonic and melodic structures with deep ties to British folk song (i.e. “Things We Said Today”). Characteristic of the early music, however, was a likely unconscious ability to blend different styles within a single song, in layers and form or between sections. “She Loves You” follows the rock ‘n’ roll stanza-refrain form found in Chuck Berry songs and African-American influenced syncopation, yet the overall effect is still one of British folksong sing-ability. Other songs pasted together very different musical styles from section to section. In “I Saw her Standing There,“ which is on your CDs, the song opens with the minor pentatonic Blues scale, but when the song arrives at the line “how could I dance with another,” The flatted third degree is retained but the climbing opening notes are resounding in the major scale. Moreover, this refrain, despite using a blue note, is more ditty than Blues. In other songs, the B section of AABA forms are actually underpinned by jazz harmonic cycles, that is, chord progressions that one would expect to find in section B of Swing and jazz pieces (ii-V-I cycles).

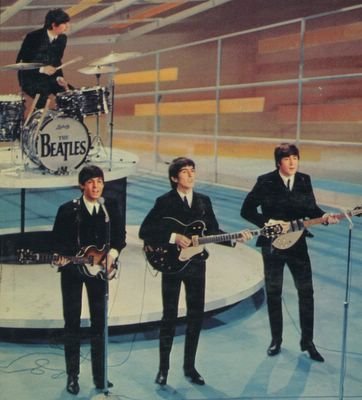

The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show

The ability to so effortlessly blend diverse styles should have been an indication that the Beatles would be more than just a commercial phenomenon. Musical experimentation began to subtly appear as early the Revolver album. To this time, their music had been characterized by strong, barber-shop style, vocal harmonies supported by drums, bass, and strummed. Instrumental solos, when they occurred, were short, and instruments played virtually no melodic role in introductions, fills, or solos. There are actually practical reasons for not incorporating solos. In their formative years, they played in clubs with poor acoustical properties and, invariably, patrons who produced a very high level of noise level. Solos simply would not have been heard.

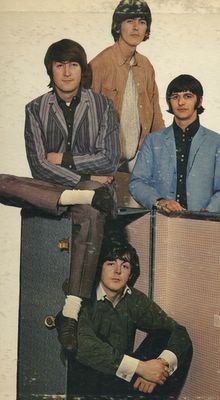

A more intimate photograph of the young Fab Four

The experimentation from revolver onward is the result of the nurturing of their producer, George Martin. Martin can reasonably be called the “fifth Beatle.” Under his influence, Lennon and McCartney were exposed to different types of music including modern classical and to different instruments for making music, in particular, the symphony orchestra. Martin also scored the accompaniment music that featured these instruments, composing many of the polyphonic lines or instrumental solo sections. Among the instruments, classical ensembles, and just plain unusual instruments that found their way in Beatles songs are the harp, the harpsichord, the string quartet, the concert brass band with woodwinds and brasses, the calliope (the organ on the Merry-Go-Round), and the penny-whistle, to name a few.

Martin’s influence is especially apparent in the Beatles’ later studio works, undertaken when the fatigue factor of non-stop touring grew to be too much. The ground-breaking album was, of course Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The advances in studio recording techniques rocked the commercial popular song world, prompting a fine response album from Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, Pet Sounds, and a not so fine album from the Rolling Stones, On Her Majesty’s Secret Request.

As noted, the musical experimentation had started several years before the making of “Sgt. Pepper.” The use of the ‘cello in “Yesterday” is well known and adds gravity that otherwise would be missing. The use of the harpsichord on “In My Life,” complete with a Baroque style instrumental solo, somehow does not seem out of place. The string quartet in “Eleanor Rigby” was a startling and haunting beautiful excursion into new areas, and a surprise in its commercial viability.

More sophisticated recording experiments went almost unnoticed. The studio experiments were driven forward by developments early in the century in classical art music made by manipulating sounds with the tape recorder. The tape recorder, newly-invented in the early twentieth century, was a primary tool of a school called of composers who called their art “musique concrete.” This group experimented with recorded sound by speeding and slowing the recording, playing the tape backward, and splicing for effect. The aural subjects were not necessarily musical—a common sound such as a tea saucer spinning to stop on a table top or the sound of a backhoe at work could form the basis of a musical composition. The same group would later embrace the synthesizer.

“I’m Only Sleeping” features a solo that uses some of the techniques of “musique concrete.” Here the notes of the guitar solo are played backward by Harrison (I assume) and recorded. Then the tape is reversed so that the notes come out in the correct sequence. Since the sequence of sound of a note played on the guitar is first the pop of the pick being driven through the string, a strong peak in loudness, then a rapid decay, the effect of the reverse tape is quite stunning and anticipates later sounds created by the synthesizer!

The incorporation of ambient noise, such as the sound of the audience before a concert begins (“Sgt.Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”) or the sounds of a engine and crew of a submarine at work (“Yellow Submarine”—and you thought it was just a kiddy song!) were bold explorations that ultimately culminated in the transference of lessons and concepts learned by the Beatles in the making of their movies. In “Sgt. Pepper,” the Beatles created the aural equivalent of an event, in this case, a concert, that is thematically unified and unfolds, in sound, in the same way that a movie unfolds visually. Nearly every piece is relates, in one way or another, to the central idea, and the music is framed by reprise music. The idea moved the popular music world forward. To that time, each song was conceived as a complete entity designed to stand alone.

Setting the Music World on its Ear: "Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band"

A collection of related songs was not enough to make the album revolutionary. The Beatles, with the help of George Martin, created a world into which the listener was carried and which functioned in much the same way as musical theater. In this world, each song was a cog in a larger whole, and the larger whole was cast in the context of a live benefit concert with “bookends” formed by the same opening and closing title song, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” The “storyline” is driven forward as a series of vignettes about individual characters and aspects of their lives. Since they would derail the literary point of the project, there are no love songs on the album.

The variety of musical styles and instrumentation on the album also significantly contribute to the sense of “other world.” In addition to the standard instrumentation of the rock ‘n’ roll band, the listener hears stage band, clarinet, harp, sitar, calliope and the musical styles they engender. The stage band plays two-step marching music. The clarinet and stage band, in their application on “When I’m Sixty-Four,” is a vestige of the Swing era though the two-step framework dates from the marching band and the Foxtrot. Curiously, the song was composed when McCartney was fifteen, long before he became a Beatle. The harp supplies the delicate but almost classical background to “She’s Leaving Home,” and the sitar spins out both Harrison’s passion, Indian music in “Within You Without You,” and adds to the acid trip alleged by music critics in Lennon’s “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” In “Mr. Kite,” the calliope brings the circus, as well as majesty and terror, to this fantasy world.

The “other world” created on the album was not possible without progressive studio effects created by George Martin. The listener is drawn into the world of Sgt. Pepper from the very first sounds on the recording, the ambient sound created by the talking of the audience as it awaits the beginning of the show. Ground breaking studio effects abound throughout the album and help to unify it. Indeed, the record is among the first that could not be replicated in a live performance.

The crowning technological triumph, however, is found at the end of the dream sequence, which is also the end of the piece, in “A Day in the Life.” It is especially remarkable considering the technology that Martin had to work with. The most advanced tape recorders were four-track units, today available for home use at any music store for about $150. Since each subsequent copy of a track deteriorates in its quality, Martin was able only to link together two four-track recorders for all his effects, and the first four tracks were used by each Beatles as he recorded his part. To gain a perspective, an analogy may be made to the space program: the Mercury space flights were controlled by a bank of computer less powerful than the 386 models of more than a decade ago!

The coup is found in the length of sustain of the last chord of “A Day in the Life.” Martin accomplished the incredible duration of sustain by using four pianos upon which the same chord was simultaneously struck. At the instant of the chord, the recording levels were set relatively low. As the sound began to decay, the engineer gradually increased the “gain” or level until the chord finally died away.

Mick Jagger

The earliest and strongest influences on the music of the Rolling Stones were American Blues and Rock ‘n’ roll, and these are influences that the band has never strayed far from. The music was edgy and hard-driving from the onset. The lyrics, like its American cousin, did not focus on love, but the subjects often represented dark celebration. “Sympathy for the Devil” represents this dark side, but also represents the brilliance of Richards and Jagger as songwriters and the concepts that made them famous and historically significant. More so than other early rockers, the Stones stayed closer to African and African-Carribean (Latin, especially Cuban) rhythms in their backbeats and delivery. The adherence to these rhythms gave the early music of the Stones its energy, rough edge, compelling sinister quality, and a character wholly distinctive from the music of their contemporaries.

In "19th Nervous Breakdown" and Sympathy for the Devil," the underlying rhythm is not a rock one, but is the "Bo Diddley" clave rhythm also found in Buddy Holley's "Not Fade Away." Moreover, its use greatly enhances the sinister quality of the lyrics of both songs. In "Sympathy for the Devil," it imparts a Caribbean “vodoo” backdrop to the song!

The Stones also drew upon other musical cultures for inspiration. Arabic music influences are evident in “Paint It Black.” Like “Sympathy,” “Paint It Black” lives on the dark side, telling the story from the point of view who survives the death of his lover. The energy and surreal quality of the song do not come from rock but, as noted, from the music of the Arabian marketplace. Drawing upon Arab sources is, in a sense, drawing upon one of the ancient sources (along with music of the Indus Valley) that participated in the formation of African music styles. In quality of concept and music, “Paint It Black” easily outstripped the music on contemporary commercial radio, and gave evidence that the Stones were not a garden variety rock ‘n’ roll band.

Throughout the history of the band, the experimentation has pushed the limits of the traditional definition of rock ‘n’ roll and its topics without destroying the basic tenets of the style. With the exception of "On Her Majesties Secret Request," the music has always retained its energy, edginess, and certainly its rudeness but has also brought to the table and intellectual component that challenged the status quo. As noted, "On Her Majesties Secret Request" was the not so successful response to the Beatles' "Sgt. Pepper" album. Brian Wilson launched his similarly unsuccessful response with his "Pet Sounds" record, though some music fans will disagree with this assessment.

<< Home